Books

Deep Halder’s ‘Blood Island’ Brings Back The Haunting Memories Of Marichjhapi Massacre

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jun 05, 2019, 07:08 PM | Updated 07:08 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

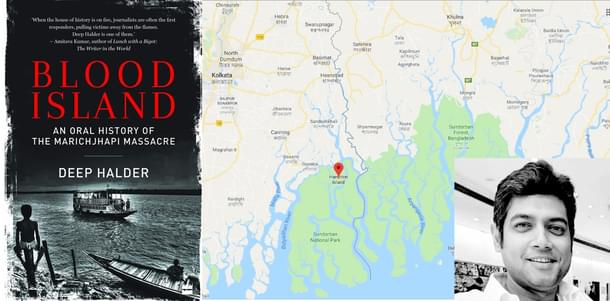

Deep Halder. Blood Island: An Oral History of the Marichjhapi Massacre. Harper Collins. 2019. Pages 176. Rs 399.

The book is just 170 and odd pages. But when one reads it, it creates a very strong and bitter feeling of betrayal. It takes an irritatingly objective look, though not explicitly, at the ‘oral narrations’ the author has collected about an event, which is central to this book. It does not ask the reader to believe what it says. There is little propaganda. There are no attributions, no explicit accusations. But we all stand vindicated in the end.

I am not a Bengali. I was not born when this nation was partitioned. When the events central to this book happened, I was a toddler. Yet, I feel after reading this book that I am as much responsible for that betrayal that ran along with the blood that spilled and mixed with the Sundarbans waters.

The book is Blood Island: An Oral History of the Marichjhapi Massacre by Deep Halder.

In The Backdrop Of Sundarbans — Beautiful Forest

There are only a very few papers and publications that study these events, which are today known as Marichjhapi Massacre. Even in these, most of the studies frame the events as the ‘upper caste’ dominance in the Marxist party unit of West Bengal, and the central cause is attributed to the ‘Dalit’ nature of the victims.

It is often forgotten that the very origin of the problem is the two-nation theory, which was theoretically at a non-emotional level accepted by Marxism. Marxists of Bengal as Marxists elsewhere had a preferential bias in favour of political Islam than with the so-called 'polytheistic’ Hinduism, which was more a threatening undefinable theo-democratic jungle.

The seeds of Marichjhapi Massacre were sown in the false alliance built by colonial and later ‘Dalit’ narratives of the scheduled communities of Bengal, sharing common socio-political interests with the Muslims. They, thus, became an effective tool because their leaders furthered and strengthened the Islamist separatist politics.

Nehruvian secularism, which in a way axiomatically agreed with this colonial and later Marxist view of society, meekly accepted this. However, with the Partition and realisation of East Pakistan, the relations between the Muslims, the rulers and the Namshudra Hindus, the rules changed drastically.

The sword of Islamism came out and the worst sufferers were the Scheduled Caste Hindus of East Pakistan. The book does not delve into all these. It just gives you facts — cold facts. And when you fit them in the historical context, it foretells what awaits every Hindu in the near or distant future:

Another heavy influx was witnessed between December 1963 and February 1964, following the disturbance sparked by the loss of Hazrat Bal from the mosque of Srinagar in Kashmir. The indiscriminate killings, rapes and looting in Khulna, Dhaka, Jessore, Faridpur, Mymensingh, Noakhali and Chattogram drove out more than 2 lakh refugees from East Pakistan. Out of these, 1 lakh came to West Bengal, 75 thousand to Assam and 25 thousand to Tripura.Jugantar newspaper, 7 April 1964.

The book is an oral history recorded from nine people, who lived through the events and it includes Kanti Ganguly, the minister in charge of Sundarbans, under the Jyoti Basu government.

The first chapter begins with the story of a father and a son, Sukhchand and Sachin. They soon realise that all of a sudden the land of their birth was no longer India. India had 'become a cuss word’ and that Hindus were no longer safe here. Sukhchand and his son along with scores of refugees cross the border and come to India — West Bengal. Soon they realise they had become ‘humanity’s leftovers’. Nehruvian — leftist state machinery — treats the refugees with no empathy.

They are back at the station, their belongings packed into tiny bundles. They will go to Marichijhapi (sic) by themselves, they decide, with cold resolve in their hearts. ... There are cops at Barasat station, armed and watching them with narrowed eyes. Walking next to Sukhchand is a sadhu from Mana Camp, a man with eyes red from cheap alcohol. ‘Jai ma Kali’ he roars. ... A khaki tries to snatch away a woman’s belongings, but she resists with all her might. He kicks her hard. Half-boiled rice scatters on the platform and the woman recoils in horror. The red-eyed sadhu roars and pierces the policeman’s thigh wiith (sic) his trident. Drops of blood fall on the rice. Sukhchand rushes out of the platform with Rangabou and the boys as teargas and lathis rain down on refugees. Screams and gunshots fill the night sky.

Remember that these are refugees, who come from East Pakistan escaping a humiliating ‘holocaust’, to the land where they think their own people live — people of their religion, dharma, culture and language. But here, they encounter a secular state machinery, which sees embracing them not as its organic duty but as a burden — an unwanted load for the state.

Safal Halder, in his narration, speaks about how he escaped a Muslim mob that tried to attack him and his family while they were fleeing East Pakistan. He still has the scars of the wound he received on his hands while defending his family. He makes sure his wife was safe with the refugee group before he falls unconscious due to loss of blood. Later, he would, with the same fear, see if his wife is safe or whether she was abducted by policemen of Marxist regime during the massacre and cleansing of Marichjhapi.

I got those scars when my wife and I were crossing the border on foot. A group of Muslim men attacked us with axes. I asked my wife to run as I tried to hold them back. I was staring death death (sic) in the face but I wanted her to be safe. Two sharp blows fell on my head. I lost consciousness and dropped to the ground.

And then 10 pages after:

One night, someone came and dropped a bottle of poison into the tube well. Thirteen people died the next day. Babies were dying like rats from diseases, and women were afraid to venture out for fear of being raped by policemen. ...I feared for my wife’s safety as women were being taken away by the police. When I heard what happened I sank into depression.

How about Hindu organisations? Did they come forward to help the refugees? They did and they were stopped by the Marxists. Also, there was at least one voice in West Bengal which told Safal Halder that the refugees should not trust the Marxists, not because they were the so-called upper castes, but because they were Marxists:

We learnt that Ramakrishna Mission and Bharat Sevashram Sangha wanted to help us but the government did not allow them. ... In Calcutta, I used to stay at 136, Jodhpur Park, in the house of Subrata Chatterjee, a renowned engineer. ... Chatterjee told us not to trust the communists in power. ‘I hate these bast*rds,’ he would say. ‘I have seen the ugly face of communism in Soviet Russia. You should not rely on the government and build an island community on your own.’

The Marxists also did not hesitate to play the communal card. They played the Muslims against these refugees.

In his narration, Sukhoranjan Sengupta, who as a reporter associated with Anandabazar Patrika, remembers how Fajlur Rehman, a Janata Party leader, confided to him that "Basu was trying to make him speak up against Hindu refugees in Marichjhapi" but Rehman refused. Instead, he advised Basu to visit the Dandakaranya refugee camps along with the prime minister to witness their plight.

The choice of Rehman reveals the diabolic mind of Basu. During the 1966 refugee riots, a building belonging to Rehman was set on fire by Hindu refugees. So Basu thought now Rehman would oblige Basu. But there was something deeper as narrated by Sengupta:

It was not my intention to bring up Rehman’s Muslim identity or the fact that Jyoti Basu was trying to play the religion card. But it is true that after 1977 , the CPI(M) had built up a powerful Muslim lobby in various pockets of West Bengal, especially in the Basirhat-Hasnabad region where Muslims, for historic or economic reasons, were not favourably disposed towards the Hindu refugees of Marichjhapi.

What should be noted here again is the natural affinity of Marxists towards Islamism. Once the initial shocks and after-tremors of Partition slowly subsided, the Marxists in the state would rather use the Islamist weapon against the refugees than share the resources of the state rightfully with their own cultural and linguistic brothers. The ex-communists could recognise in the ruthless suppression of Marichjhapi and the killing the very core CPI(M) philosophy.

Niranjan Haldar, himself a refugee from East Pakistan and now an ex-communist, explains:

The fact is that these refugees were a self-sufficient, independent lot — they used to manufacture bidis and sell them. They used to make breads and sell that, the flour for which was also grown by them along with fish cultivation, boat-making... This self-sufficiency was a threat to CPI(M)’s core policy — help the needy and the downtrodden, in exchange for their support vis-a-vis votes. But the Marichjhape (sic) people didn’t want anything from the government; all they wanted was a play (sic) to stay.

There are many striking resemblances to the ways Stalin or Mao used to punish the ‘nationalities’ that dared to raise their voice against their Marxist state: economic blockade, torture by police, rape of women, poisoning the water supplies, stopping the medical services and ultimately unleashing the brutal killing power of the state. But the greatest success that the CPI(M) had, which even Stalin and Mao could not have, was the silencing of the media even in a democratic Indian state.

Then there is what Mana Goldar has to say. She was named after the Mana camp, where she was born. Her memories tell us about the horrific history of thousands of refugees like her that was hushed by the state and mainstream media. There is remarkably no bitterness in her voice only pain of the memories: "What do I say, babu? You can’t change the past, can you?” Mana sighs. So writes Deep Halder.

Mana’s sigh is the sigh of a wounded nation though, with wounds inflicted by the nation’s own sons because they could no longer feel for their own kith and kin. And then as Deep Halder talks to Mana Goldar, Santosh Sarkar enters in his crutches. He had lost his leg at Marichjhapi on 31 January 1979. He remembers, how in the face of bullets and definite defeat, something entered him.

Deep Halder records:

Sarkar has always been a Swami Vivekananda fanboy. He says the Swami’s spirit entered him that moment when he addressed his fellowmen, ‘Brothers, this is no time to run and hide. Even if you run, the police will open fire on you. They do not treat us refugees as humans. If they did they would not have drowned our women. Ever since we, the Hindu refugees, have come to this country, the state has treated us like dogs. Whether in the refugee camps or outside, we have been shown no dignity. Today, let us fight back. If we have to die, let us die with dignity.’

And the ‘memories’ that should shame every Hindu in this country continues:

He would know later that CPM cadres had landed in Marichjhapi that day, fired at, killed and raped islanders and looted their belongings. The mayhem continued for the whole day. He would also hear later how the police did not even spare children. Bayonets had been thrust into fifteen school kids - aged between five and twelve - who had taken shelter inside the thatched hut that was their school. Their skulls were crushed. The kids had gathered there to make arrangements for Saraswati Puja, which was to be celebrated the next day. The police had smashed Saraswati’s idol before they left.

According to Sarkar, that day alone not less than 1,700 people lost their lives. He lost his leg and survived to record it four decades later. But Kanti Ganguly, who was the minister of Sundarbans affairs in Basu government, during Marichjhapi Massacre would dismiss all that: "Rubbish. Even if I put the death toll at eight or ten, it would be too high a number.”

At last, there is Manoranjan Byapri. His autobiography, Interrogating my Chandal life: An Autobiography of a Dalit (2018) had become quite famous. To him, whose father’s chest bones were broken by the police of Marxist Reich, the cause for Marichjhapi was clear:

Caste hatred led to Marichjhapi massacre. ...If the settlers had been Brahmins, Kayasthas and Baidyas there would have been no action. ...Marichjhapi settlers had declared that they had no need of any government assistance. They were self-sufficient and had built their own township. But this is not what the Communist government wanted. Their deal was: ‘We will give you rice, you join our rallies, vote for us.’ If these people became independent, capable, which they were turning out to be, they wouldn’t depend on the government for food and cloths (sic).

The last chapter is a visit to Marichjhapi itself. There the author meets Dinabandhu Biswas, a 66-year-old teacher at an ashram ‘Baruipur Sitakundu Snehakunja’, and he recounts with tears freely flowing as he goes through the memories.

This is indeed an eyewitness account:

They took the islanders as prisoners, shot them in the head, put them in sacks, tied them to rocks and dropped them deep into the river so that the corpses don’t float. Mini Munda, a Kumirmari resident, had given shelter to a Marichjhapi family during the eviction drive. The police got to know, kicked her door open, took the family away and shot Munda in the head. She is also Marichjhapi’s martyr, though she was from Kumirmari.

The book ends with an emotional account of one of the survivors of the massacre — 85-year-old Narayan Banerjee:

The rickety journeyman gasps for air with his mouth wide open. Scared, I hold his arm, ‘Aapni theek achen? Are you okay?’ ‘Baba do not take me to the past. It is too painful. Too painful.’

The memories which unfold through this book reveal one thing. Comrade Jyoti Basu did make Indian Marxism proud. He had well earned a place among the totalitarian dictators of socialist and Marxist variety who had exhibited genocidal tendencies and attained that legacy — Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot. Jyoti Basu in a way outshines all these criminals against humanity. He could push under the red carpet his crimes against humanity in a democracy, and even though he was not the ‘dictator’ of the entire nation.

Ultimately, the book raises certain serious questions for this reviewer as a Hindu. The pattern is very clear: the caste divisions and the crime of untouchability in the Hindu society was used by the colonialists and then Islamists to categorise a large section of the scheduled community to alienate themselves and identify with the interest of Islamist politics. This leads to a large section of the population to become unwittingly hostages in a land turned hostile.

Once East Pakistan became a reality, the Dalit-Muslim bonds evaporated and the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities became identified as ‘Hindu’ or pagan. They naturally looked back to India as their hope — their natural motherland. As they came here, they were treated in an equally inhuman way. This was treason.

The Hindu organisations did come forward to assist without expecting anything in return. But the Marxist regime did not want a self-reliant community but only a vote bank. Then came the massacre, the modus operandi of which matches similar crimes against humanity committed by Marxist dictators throughout the world. However, the blame is ultimately put on ‘caste’ and indirectly on Hinduism itself.

Multiple accounts in the book point out that the refugees identified themselves culturally and emotionally with Hinduism. The Marxist-Islamist angle to the problem also had surfaced, though very lightly, in the narrative. Of course, the refugee problem itself has its roots in that, is another thing. What about the caste angle? Hindu society has that problem.

Then there are forces in Hindu society which unite the communities in an egalitarian manner. But there are other forces that want an essentialist stereotype narrative for perpetuating their own vested interests. The colonialists and evangelists then, Islamists and Marxists, and the left liberals now, want the scheduled communities to be the perpetual other. They deepen the faultlines. They trade new hats of victimhood for the old — ‘Dalits’ now. But remain separate and become our ideological and political tool, they say. But when their utopias emerge, pagans die and die horrible deaths.

Deep Halder had done a great service to humanity by writing this book. Through the past he had shown us our future too.

Looking at my home state, I see how the self-reliant proud geniuses from the so-called scheduled communities have been treated with contempt by the progressives. Even when the entire society celebrates them, caring nothing about their caste identity, the progressives and Lutyens have to point out that they are ‘Dalits’. They have to behave in a specific manner. If a music genius arises who redefines the very way the entire society experiences music, even he has to be defined by Dalit label for these upper caste progressives.

If a scheduled community wants to declassify itself and merge with the larger Hindu society on equal terms, then lynch-mob journalism gets unleashed on the leader of that community. Jyoti Basu wanted no self-reliance for the refugees. We support you with pittance and you vote for us, said the Marxist. We give you place in our literary festivals and you wear the Dalit cap, say the modern progressives. But both these paths of alienation always lead us as an entire society to only one place: dead bodies of our children thrown into the dark rivers in the near future.

Do not ask to whom Marichjhapi happened. It happened to the disunited Hindus of the past. And it will happen to disunited Hindus of the present and disunited Hindus in very near future. First, there and ultimately here where we live — you and me. Their past is very well our future. Buy this book. Read it. And when you read the book, remember that this is not about the massacre that happened to Bengali Hindu refugees in 1979, but this is the future all Hindus are staring at, if they do not sink their differences.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.