Books

The Kashmiri Pandits: A Wail That Went Unheard

Ramesh N Rao

Oct 11, 2018, 11:27 AM | Updated 11:27 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Mitra, Rajat (2017). The Infidel Next Door, Createspace Publishing. Soon to be republished by Utpal Publications.

There were at least 350,000 to 400,000 Hindus in the Kashmir Valley in the 1980s, though low estimates put that number between 160,000 and 170,000. The low estimates are one indication of the attempts to wish away the violence, the rapacity, and the cussedness of the Muslim population in the valley, who abetted by Pakistani money from across the border, brutalised the Kashmiri Pandits.

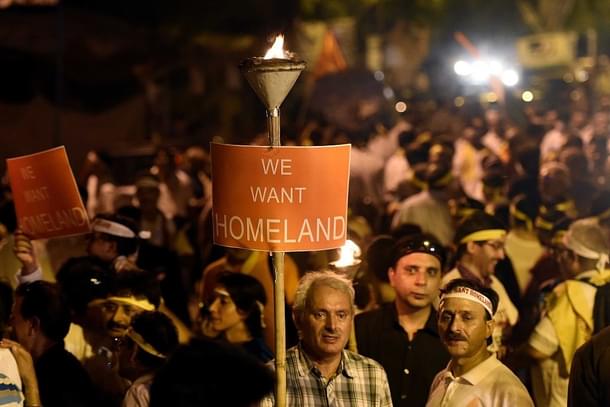

The mass ‘exodus’ of the Pandits, who lived in the valley for over five millennia, to nearby safe havens in Jammu, and across the state borders to shanty towns hastily constructed in the environs of New Delhi/Delhi is barely recalled 30 years later: where there should have been scores of popular movies and documentaries, hundreds of books on the plight of the Pandits and the cussedness of their former Muslim neighbours, and pressure from human rights activists in the country and around the world to punish the guilty and help the Pandits reclaim their homes and their lives, what we have is silence, mostly silence.

Yes, there are sporadic references to what happened and why, and there are even some cunning theses apportioning all the blame on to the victims. I believe there are more novels and books describing the angst and the anger of Muslim men and youth who want to drive the Indian Army and Indian policemen out of the valley, and make Kashmir “independent” than there are books on the plight and enormous loss of the Pandits.

It is in this context that we should welcome Rajat Mitra’s book, The Infidel Next Door. It is a powerful though melancholic story of Kashmir – which does not get a detailed exegesis – playing out in the life of Aditya Narayan in the setting of the present. This carefully crafted tale, beautiful in its simplicity, and devoid of the pretentiousness of so much of modern Indian writing, has not found a prominent publisher who could have enabled the big lights to shine on this powerful tale.

Why the shyness of the otherwise eager publishers who are happy to sell tales of rape and murder, of Hindu mischief and “minority” munificence to publish this novel in which young Aditya seeks to rebuild an ancient Hindu temple destroyed by Muslims in the Kashmir Valley? Mitra says that because “…of its references to bigotry and religious violence no publisher in India agreed to publish it. Though they called it a book of courage and a voice against the fear that is being created in the name of religion they felt it would invite trouble”.

There we have it – either pure lies or simple mischief – for nothing could be further from the truth about this book than it is a rabble-rouser or a screed. Written by a trained psychologist, who has worked with trauma victims – from religious violence to sexual violence – this is indeed a richly layered tale – where it is not just the black of the Muslim burqa or the white of the Brahmin dhoti that lead us on but the many shades of light that expose the lives of finely drawn characters.

The Infidel Next Door is not a simple, let alone a simplistic tale of modern political umbrage or of religious persecution and revenge. It is a beautifully narrated and skillfully woven work of fiction that takes us on a journey from Banaras to the Kashmir Valley made by young Aditya, gifted in the learning and telling of Hindu scriptures, and who is urged by his guru and mentor to go to the valley to rebuild the temple that his ancestors had built and given their life to, including Maheshwar Narayan, his ancestor, who had been beheaded while trying to save the temple he officiated in.

Aditya makes his way to the valley with his mother, Gayatri, and father Krishna Narayan, a rather conservative if not a bigoted priest. Travelling in the train is Professor Baig, Vice Chancellor of the University of Jammu, and a keen historian, who encourages Aditya to go on this journey to the place where dangers lurk, and where next to the destroyed temple is a mosque. Prof Baig also gets Aditya to find out more about the “Killing Fields of Kashmir” – Battmazar/Bata Mazar – where hundreds of murdered Hindus were buried en masse in the Dal Lake.

The protagonists in this tale are Aditya Narayan and his mother Gayatri; Nitai and his sister Tara – outcastes, who have escaped from the police and ended up in Aditya’s temple in Kashmir; Javed, who is Anwar’s good friend and who pines for Zeba, Anwar’s sister; Imam Saab, Anwar and Zeba’s father who is tricked into playing Haji Chacha’s cunning cards; Zeba, who falls in love with Aditya, but ends up marrying Salim, a trained terrorist; and Anwar himself, who starts off as a peacenik but ends up wanting the “infidel” out of Kashmir. Each one is skillfully drawn and lovingly portrayed, and we get to know how their lives get entangled in this layered tale of religious bigotry where the inexorable nature of the conflict between those who espouse monopolistic religious beliefs and those who are in the pursuit of god via the paths of experience and philosophical inquiry get played out.

A pioneer of sorts, Dr Mitra has had to deal with the Indian disdain for modern psychology and in seeking help from trained therapists. “Different spiritual practices, group singing called bhajans and religious dances still replace psychotherapy where a lot of grief is released,” he says. Mitra has written about his work with Muslim men who have been imprisoned for acts of violence and sabotage, and of their sense of loss and anger when they heard about the destruction of the Babri Masjid. But how have Hindus responded to the nearly a 1,000-year-long series of depredation of their land, their temples, their kinfolk and their culture? Dr Mitra wonders how Hindus might have felt seeing the Somnath temple destroyed or when mosques were built either adjacent or over destroyed Hindu temples. “How traumatic would it have been, and would it have traumatized the whole community and then the whole country?” wonders the author, and in this novel we can see some of that dynamics still in play in modern India.

Mitra’s own life story is fascinating: his wife is Kashmiri, and so he knows quite intimately the tragedy and the trauma of Kashmiri Pandits; he has also worked with Muslim militants lodged in Indian jails, listening to their stories of indoctrination and religious bigotry; and his work in therapy and trauma care offers him a perspective of the world that most of us, identifying with our tribe and our party, cannot access or refuse to embrace. But beyond all that is this really gripping tale, crisply told.

It needs to be read!

Ramesh N Rao is Professor, Department of Communication, Columbus State University