Books

Swami Vivekananda And Two Criticisms In Contemporary Intellectual Discourse

Saurav Basu

Jan 27, 2016, 11:01 PM | Updated Feb 12, 2016, 05:23 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Neither is Vivekananda glorified without reason and nor was he overawed by the West’s interpretation of itself

In a curiously worded criticism, Koenraad Elst who is otherwise arguably the finest authority on the emergence and ideology of contemporary Hindu nationalism, alleges that ‘Swami Vivekananda is over-glorified and made the patron of too many institutions….Thus, scholars of Hindu philosophy consider his knowledge…very third-rate, and his influential interpretation of Patañjali’s Yoga Sutra even harmful…’

Elst is apparently unaware that dissemination of Vivekananda’s message received minimal support from the state in independent India. Hence, the great receptivity and persistence of Vivekananda’s message in the modern Hindu consciousness as affirmed in Gavin Flood’s frank assessment that ‘Vivekananda’s Hinduism is synonymous with the rapidly progressing “middle class Hindus” of today’ is derived principally from the appeal of his message. Elst too does credit Vivekananda with instilling vital ‘self-confidence’ in the Hindu population at a time when in the Hindu scholar Ram Swarup’s words, ‘a defeated nation was trying to restore its self-respect and self-confidence through self-repudiation and identification with the ways of the victors.’

Sister Nivedita explains in her introduction to Vivekananda’s complete works the subtle philosophical ingenuity which, ‘while proclaiming the sovereignty of the Advaita Philosophy, as including that experience in which all is one, without a second, (Vivekananda) also added to Hinduism the doctrine that Dvaita, Vishishtâdvaita, and Advaita are but three phases or stages in a single development, of which the last-named constitutes the goal.’ Vivekananda’s Hindu philosophy is thus an innovation which could be said of several other Vedantists since the time of Shankara. Critical evidence will need to be marshalled before suggesting that Vivekananda imposed such ideas on the texts as were contrary to their original spirit.

Elst is also perhaps disturbed by Vivekananda’s emphasis on anubhava (experience) over agama (scriptural revelation) as the essence of Hindu thought and the idea of Hinduism as a ‘scientific religion’ which emphasized empirical validation of spiritual precepts as the culmination of all sadhana. Yet, Vivekananda was merely following the illustrious Yogic lineage from Patanjali himself. Edwin Bryant in his monumental commentary on the ‘Yoga Sutras of Patanjali’ recognizes that while ‘Patanjali was an orthodox Hindu, which means he accepted the truth of divine revelation, agama – even if he holds that the experience of these truths is higher than simply belief in them.’

Vivekananda’s statement ‘we believe all religions are true’ has to be seen in conjunction with the fact that Vivekananda was asserting the plural Hindu heritage of according legitimacy to the perusal of divergent paths for religious satisfaction. As he said:

We know that all religions alike, from the lowest fetishism to the highest absolutism, are but so many attempts of the human soul to grasp and realise the Infinite. So we gather all these flowers, and, binding them together with the cord of love, make them into a wonderful bouquet of worship.

So for Vivekananda all religions were not same, all religions were not equally tolerant, all religions were not equally liberal, all religions were not equally efficacious in reaping spiritual fruits and lastly, all religions were not equally advanced in their approach to the ‘truth’.

Elst further criticizes Vivekananda for his appropriation of Western colonial assumptions on Hinduism which contrasted the dichotomous ‘Materialistic West’ against the image of the ‘Spiritual East’ and undermined Hindu civilization by reducing it ‘to its spiritual component which was unjust to the variegated Hindu traditions in art, architecture, statecraft, mathematics, etc’. Elst’s argument is historically untenable for the following reasons.

First, Vivekananda was immensely proud of Hindu secular and material achievements. This is evident from an American newspaper report from the Brooklyn Standard Union dated February 27, 1895 titled ‘India’s gifts to the world’. Vivekananda is reported to have told his American audience that India had “given to antiquity the earliest scientifical physicians…modern medical science… by the discovery of various chemicals and by teaching you how to reform misshapen ears and noses. Even more it has done in mathematics, for algebra, geometry, astronomy, and the triumph of modern science — mixed mathematics — were all invented in India, just so much as the ten numerals, the very cornerstone of all present civilization, were discovered in India, and are in reality, Sanskrit words…”

The limitation of Vivekananda preaching the virtues of Hindu exact sciences in an age where they were largely undiscovered and while belonging to a colonized nation known for its snake charmers and widow burnings cannot be overstated.

Second, Vivekananda defied essential Orientalist assumptions about Hindu faith (mysticism and other-worldliness) since his radical interpretation of the Advaita Vedanta cannot be reconciled with the Oriental image of the ‘Indian Brahmin dreamily contemplating the fate of the universe.’

Third, Catherine Rolfsen in her sympathetic and illuminating account of Vivekananda’s engagement with Orientalism (Resistance, Complicity and Transcendence: A Postcolonial Study of Vivekananda’s Mission in the West) understands that Orientalist critique overlooks Vivekananda’s successful manipulation of the dominant Orientalist discourse. This is done in an effort to negotiate India’s position in the world as an equal partner by asserting its ‘spiritual superiority’ through the representation of ‘Vedanta as a unified, inclusive, universal, tolerant, humanitarian, and rational faith system.’

Fourth, as Rolfsen also points out, the idea of a ‘spiritual India’ as a product of Orientalist discourse in no way discounts its potential veracity. For Vivekananda, the idea of a spiritual India was not some abstract category but an organic living ideal which constituted ‘the key note of the whole music of national life’ unlike ‘political power as in the case in England…artistic excellence in case with Rome and philosophical uniqueness as with Greece.’ The unorganized life of a sannyasin was for him the embodiment of the uniquely spiritual trait of Indian life.

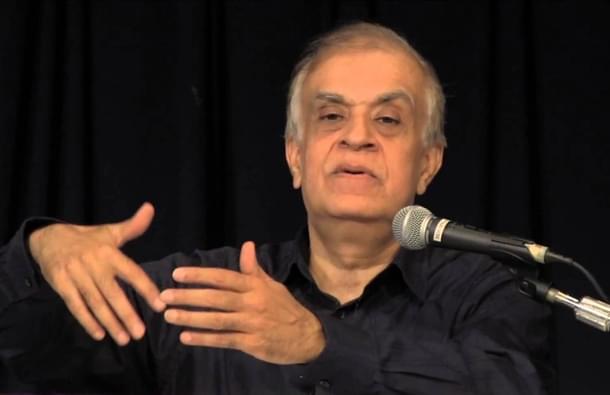

Rajiv Malhotra is a leading public intellectual who has challenged several assumptions of mainstream American academia with their intrinsic Eurocentric and Abrahamic worldviews which tend to undermine Hinduism.

In his well-received book, Being Different: An Indian challenge to Western universalism, Malhotra regrets that:

‘Vivekananda and others were content without a formal study of the West on dharmic terms and largely read what the West’s own proponents and critics were producing, as opposed to studying the West systematically in dharmic terms’.

Malhotra considers that they did not reverse the gaze unlike him which resulted in him attaining several hitherto hidden insights into the nature of Abrahamic religious thinking which was oblivious to others including Vivekananda. Curiously, as we shall see some of these insights were well established in Vivekananda’s thought.

First, Malhotra advocates the need for mutual respect and not mere tolerance, otherwise the idea of interfaith dialogue is rendered futility. This is equivalent to Vivekananda’s addresses at the world parliament of religions where he said ‘I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance.’

Second, Malhotra describes a “dharmic golden rule” as ‘there is no ultimate ‘other’ because each apparent other is ultimately the same as oneself. In short, love your neighbour as you love yourself because your neighbour is yourself’. This is the essence of ‘integral unity’. Vivekananda’s works reveals an almost identical principle:

“Asti, “isness”, is the basis of all unity; and just as soon as the basis is found, perfection ensues. If all colour could be resolved into one colour, painting would cease. The perfect oneness is rest; we refer all manifestations to one Being. Taoists, Confucianists, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, Mohammedans, Christians, and Zoroastrians, all preached the golden rule and in almost the same words; but only the Hindus have given the rationale, because they saw the reason: Man must love others because those others are himself. There is but One.”

Third, the concept of history centrism in Abrahamic thought was advanced by Malhotra which he defined as “the fixation on specific and often incompatible claims to divine truth revealed in history.” Within the Abrahamic worldview with a linear view of history, the access to historical revelation and subsequent obedience to God’s will (commandments) as stated in the revelation are essential for salvation. Malhotra contrasts this with the individual located within a Dharmic viewpoint where ‘it is not necessary to accept a particular account of history in order to attain a higher, embodied states of consciousness. Nor is any such historical account or belief sufficient to produce the desired state. Thus, dharma traditions have flourished for long periods without undue concern about history…’

Vivekananda also observed that except for Hinduism all ‘all the other religions have been built round the life of what they think a historical man; and what they think the strength of religion is really the weakness, for disprove the historicity of the man and the whole fabric tumbles to ground…’. In contrast, Hinduism is a religion ‘that does not depend on a person or persons; it is based upon principles. At the same time there is room for millions of persons…’ (Complete works of Swami Vivekananda, Lectures from Colombo to Almora, “The Work before Us”). Hence, Vivekananda observed that Hinduism unlike Abrahamic faiths was based upon precepts nonchalant to the historical veracity of the lives of those propounding them including Rama and Krishna. (Complete Works, Vol V, p 207-8)

Malhotra argues that “Even if all historical records were lost, historical memory erased, and every holy site desecrated, the truth could be recovered by spiritual practices.” Similarly, Vivekananda considers “Persons are but the embodiments, the illustrations of the principles. If the principles are there, the persons will come by the thousands and millions. If the principle is safe, persons like Buddha will be born by the hundreds and thousands”.

Only Malhotra can explain whether he could have arrived at his theory of history centrism without coming across Vivekananda?

Saurav Basu is an independent researcher with interests in history and politics