Commentary

A Flawed 'Press Freedom Index' — Drawn On Opinion-Based Ranking, Not Data

Deepesh Gulgulia

Apr 07, 2025, 10:26 AM | Updated 10:26 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Reporters Without Borders (RWB) is notorious for ranking India below countries like Qatar, Rwanda and Congo in its Press Freedom Index.

What gives? How could India be ranked below countries where dissent is illegal?

In this article, we peel back the layers of the Reporters Without Borders (RWB)’s opaque methodology, expose its inconsistent global rankings, and dissect the selective outrage on freedom of press in India. Because when perception replaces facts, it’s not journalism it’s agenda.

The Press Freedom Index, published annually by Reporters Without Borders (RWB), ranks 180 countries on the degree of freedom available to journalists.

It claims to assess nations based on five indicators: political context, legal framework, economic pressures, sociocultural environment, and the safety of journalists. However, the index’s credibility falters under scrutiny not because of what it measures, but how it measures.

The backbone of the ranking lies in a questionnaire-based survey filled out by a select group of journalists, academics, and civil society members chosen by RWB.

Their identities remain anonymous, and the selection process for these contributors is not transparent. This creates an inherent risk of ideological bias, especially when there’s no public accountability or scrutiny of the survey sample.

Rather than relying on hard data, like the number of independent media outlets, media reach, press plurality, or internet access, the index prioritizes perceptions and opinions.

To add to the opacity, RWB doesn’t disclose how each of the five indicators is weighted in the final score. This allows disproportionate emphasis on certain issues while downplaying others.

For instance, an isolated incident involving the arrest of a journalist in India might weigh more heavily than systemic censorship in countries with state-run media. Ironically, countries where press freedom is literally controlled by the state such as Qatar or Rwanda often rank above India simply because fewer open confrontations are visible, largely due to the absence of press dissent itself.

The credibility of any global index depends on consistency.

Yet, RWB’s Press Freedom Index regularly ranks countries with well-documented media suppression, such as Qatar (84), Rwanda (144), Congo (123) and Palestine (157) well above India (159), despite these countries offering little to no space for dissent, investigative journalism, or independent editorial policy.

In Qatar, criticism of the royal family or government is criminalized; in Rwanda, the state has been accused by Amnesty International of surveilling and imprisoning critical journalists. Yet somehow, India with a legally protected press, regular televised government grilling, and court interventions safeguarding speech continues to finish at bottom.

This discrepancy prompts a deeper question: Who funds Reporters Without Borders?

Reporters Without Borders portrays itself as an independent watchdog, but its financial underpinnings tell a different story.

In 2022, RSF operated with a budget of approximately €8 million, of which 52% came directly from public institutions, including the French government and the European Commission.

An additional 22% was funded by private philanthropic organizations, notably the Open Society Foundations, founded by George Soros, and the Ford Foundation, both known for funding media-related projects aligned with specific ideological worldviews. Another 12% came from commercial sales, and just 11% from public donations and sponsorships.

This isn’t just about money, it's about narrative control. When an international ranking body is bankrolled predominantly by Western governments and ideological donors, it becomes difficult to separate activism from agenda.

Nations like India, which pursue independent foreign policy stances or resist Western pressure on issues ranging from digital regulation to information warfare, often find themselves disproportionately criticized not because press freedom has vanished, but because the narratives don’t align.

The most glaring hypocrisy of the Press Freedom Index is revealed when one looks at where journalists are actually murdered and how these countries are still ranked above India. It’s a paradox that would be laughable if it weren’t so tragic.

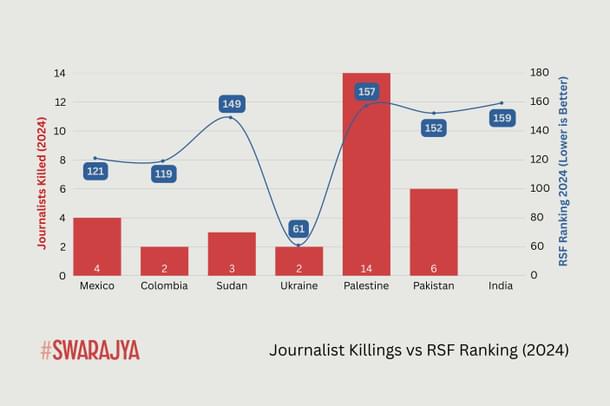

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), from January to October 6, 2024, the deadliest countries for journalists included Palestine (14 deaths), Pakistan (6 deaths), Mexico (4 deaths), Sudan and Iraq (3 each), and Colombia and Ukraine (2 each). These aren’t isolated murders or accidental casualties,they were confirmed by RSF to be linked directly to journalistic work.

Now here’s the twist: despite these deaths, all of these countries rank higher than India in RSF’s 2024 index. The visual below says it all: Red bars show the number of journalist killings in 2024 & Blue line tracks each country’s RSF ranking (lower is better):

These aren’t just statistical glitches, they are systemic contradictions. The Press Freedom Index, by its own admission, is built on survey-based perception, not on ground realities or objective data.

That’s how a country like India with over 400 news channels, 1,000+ digital outlets, and daily high-decibel government criticism, can rank lower than countries where journalists are being gunned down or bombed.

And yet, every year, the Press Freedom Index is weaponized globally and domestically.

It finds eager amplification in international media, think tanks, and even in political discourse at home. When India introduced its 2021 IT Rules to regulate OTT and digital platforms, global media quickly condemned the move as authoritarian. RSF’s ranking was widely cited as proof.

But these very critics remained silent when the European Union brought in the Digital Services Act or when Australia enforced its Online Safety Act measures that mirrored India’s in spirit and function. Apparently, what is regulation in the West becomes repression in India.

This selective outrage plays neatly into the hands of domestic political opposition and ideological factions within civil society and media. “India is sliding into authoritarianism” is a headline too tempting to resist, even when the same government ensures judicial oversight, sustains institutions like the RTI, and grants unfettered parliamentary access to the press.

The irony is almost poetic, those decrying India's press freedom often do so with complete impunity, on national television, and under the full protection of the laws they claim are under threat.

To be clear, criticism of any government is not just valid, it’s essential in a democracy. But when indices selectively amplify some violations and ignore others, the risk isn’t just reputational, it's geopolitical.

Rankings like RSF’s don’t just inform, they influence. From international media perception to foreign investment sentiment, they are wielded as soft-power tools.

As long as its foundations remain opaque, its methodology subjective, and its outcomes selectively weaponized, its rankings will continue to reflect narratives not realities.

In that context, the question is no longer “Why is India ranked so low?” The real question is, can we trust an index where neutrality takes a backseat to a fueled agenda?

Deepesh Gulgulia is a Law student. He tweets at x.com/@deepeshgulgulia.