Commentary

What Happened In Ayodhya: What Our Intellectuals Saw And Yet Did Not Know What They Saw

SN Balagangadhara

Apr 02, 2024, 06:44 PM | Updated 06:54 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Indian traditions speak of tatvadarshi’s in this world. Who are they? The Sanskrit phrase is a compound of darshi and tatva. ‘Darshi’ is someone who sees or has seen. What? ‘Tatva’, a word compounding tat and tva. ‘Tat’ means ‘that’, while ‘tva’ qualifies. It is the “-ness” in kind-ness and good-ness. In our case, the compounded words give ‘that-ness’. Thus, a tatvadarshi has seen ‘thatness’. What does this mean?

When we see an object, mostly we see it as something; perhaps, as a thing with shape, form, size, and other properties. The world and our abilities, both physical and cognitive, jointly give us what we see, namely, something which is this or that object. Assume that you see an object, but do not know or recognise it as a specific object. In that case, if asked what you see, you can point your finger and say, “I see that”. Suppose that you do not use the finger but would like to communicate nonetheless that you see something. How could you do so? Well, you can say, “I see thatness”. Here, you communicate seeing something but are unable to identify it. That is, by ascribing the property or quality of ‘that-ness’ to the object, you use language to point at an object.

In a sense, every seen object is a ‘that’ and knowing it as ‘thatness’ does not tell us what we see. In simple terms: you have seen something, you cannot identify what it is, thus, you say you see ‘thatness’. These are tatvadarshis. Even though they see something, they are unable to identify the object because they do not know what they have seen.

These are our intellectuals as well. They see but do not know what they see even if they think they know what is seen. They are tatvadarshis, not jnanis. We need the knowledgeable (the jnani) to tell us about the what: what happened in Ayodhya? The tatvadarshis cannot do this, but they are the only jnanis we have. Why did this come about and how? This important question must be answered but that is not my brief here. Instead, it is the more modest one of trying to say what could have been seen in Ayodhya. To do this, we rely on extant reports and use these. Hence, we began with our tatvadarshis.

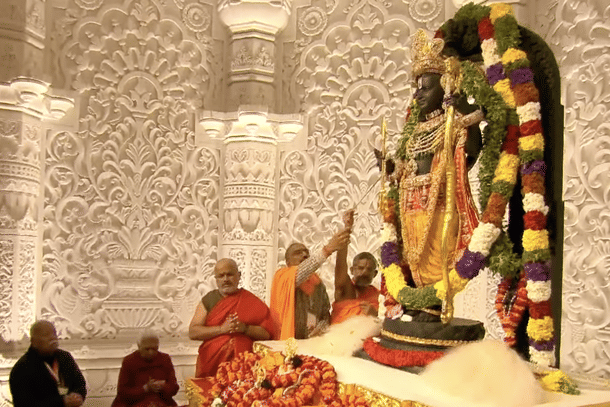

These intellectuals saw the uncommon and the out-of-the-ordinary in Ayodhya. Whether a glitzy affair or a mega-spectacle, the event appeared to astonish. It was as though the new but the familiar replaced the old and the familiar: Rama is the old and familiar king of Ayodhya; the Ram Lalla, the five-year-old, is new but the familiar Rama; the centuries-old mosque, its familiar structure dotting the skylines of many generations, is violently replaced; even though its place is taken over by an unfinished temple, Rama’s new temple is familiar even to those who have not seen it. Our tatvadarshis see politics leading a ceremony that appears deeply religious. Thus, they wonder what the event portends. Of course, our tatvadarshis have said more, but this small clutch of sentences is sufficient for now.

These sightings are refashioned into descriptions of the Hindu state, the demise of secularism, Hindu fundamentalism, the emergence of Hindu majoritarianism, the effaced boundary that separates religion from politics, and so on. Therefore, our question: is this the only reasonable description of the event or is a cognitively better alternative possible? One could give a coherent and consistent description of the Ayodhya event which, if true, predicts a disaster. But I think that an alternative description is possible which not only promises but also delivers a better future. Neither the promise nor an impending delivery makes the alternative better. What does this is its cognitive superiority: the alternative’s assumptions are less suspect, sheds a better light on issues, and resonates more intimately with experience. What is equally important is that such an alternate description generates new and exciting cognitive problems, and productively opens novel ways and areas of research. I outline three reference points that function as indicators and, in what follows, suggest a different route to answer the question, “What happened in Ayodhya?”

1. Varshney sees Modi using “new vectors of language - such as Dev se desh (divinity to nationhood)”. The ‘vector’ in this language is not new but old and ancient, if ‘Dev’ is moving towards ‘desh’. The Jews became a nation, i.e., acquired their nationhood when Yahweh, the Jewish God, entered a covenant with the nation of Israel. One should not ascribe novelty to an old use of language. Whether Modi used new vectors or stuck to the old, his speech in Ayodhya will be my first reference point. Even here, I isolate one thought which strikes me.

Modi suggests that we look at the happening in Ayodhya not as an event in the calendar but as something else, namely, as the Kalachakra from where a new age emerged. What could this thought say? This question is not about what Modi thought or tried or wanted to say because I have no clue about these. I need neither to make sense of the thought.

Historiography, as we know and practice it, maps a domain of events to another domain consisting of units of time. This mapping is not strict or one-to-one. Many elements from the domain of events can be mapped to a single element in the other domain. Then we have a many-to-one mapping: many events occurred on 15 August 1947. Thus, some simple arithmetical operations that are possible in one domain cannot be mapped to the other: hours, days, weeks, etc., give us an arithmetical sum when added to together; such an operation is not possible in the events domain because many or multiple events could add up to one event. The same applies to operations like division, subtraction, and so on. Consequently, relations and structures present in one domain cannot be mapped to the other domain.

Invariably, such a mapping is accompanied by garden-variety claims about economics, politics or anthropology or human psychology, sociology, etc. These are presented as historical explanations. Whether explanations or not, these transient events are said to be historical, i.e., of possessing historicity. Thus, any set of ideas that appears to have the form of an explanation becomes “historical” if it is about an earlier event. Of course, we must ‘prove’ their occurrence which requires archival research, etc.

Such a mapping of the Ayodhya event to a calendar is not appropriate, says Modi. What is? We do not expect a philosophical explanation in Modi’s speech, but we are treated to a contrast. That is, events in calendars are contrasted to the past. If events and the units of time are elements in the two different domains that give us historiography, by contrast, the events neither “occur in time” nor can they be mapped to units of time in what is the Kalachakra. Here, events structure time, or time itself emerges from events. The process can be linguistically communicated but it would not recount events but narrate them instead. This narration, a story, has a beginning, a middle, and perhaps even an end. But ‘the’ past has no place here because any event in this circle is past relative to what is chosen as a beginning, a present. The same applies to the future.

Thus, Modi’s remark contrasts history with the past: historiography gives us the first; narratives or stories give us the second. Both are structured: classificatory units of time provide a structure to the first; salience gives a narrative structure to events in the second. These are alternatives: as I have noted elsewhere, to give history to a people is to destroy their past. The story that made Rama live and die is a narrative enabling Rama to become a child again in our present. ‘The’ past that historiography traces is transient, which is why it disappears from our lives. Its Ayodhya and Rama might be significant to the archeologist but not to us. A narrative past, the story of Rama, by contrast, lives in our daily lives as its integral part. Modi seems to draw this contrast when counterposing the calendar to Kalachakra. What, then, is the new age he talks about?

2. In this new age, the tatvadarshis see politics and the state fusing with religion. Here, the boundary between religion and politics blurs, the secular and the religious intersect, and one where a religion of the majority ends up as Hindu majoritarianism. This is the emerging age they see manifesting itself and explicitly confirmed in an event where the PM of a nation leads a religious consecration.

To assess the above description better, consider the fragmentary video clips circulating in the social media about Modi’s motorcade in the streets of Srirangam. He went there to take a dip in the sea, one of the 11 acts he performed to qualify himself for the pran pratishtha. As the vehicles pass through the town, we hear some chanting and see some people raising hands. The raised hands were mostly from old men, naked from the waist up, wearing yagnopavita, and carrying marks on their foreheads. I learnt later that the chanted verse was from the Ramayana, the verse ascribed to Kausalya, Rama’s mother. Without deciphering the chant, I recognised ‘Ashirwad’ in the gestures of the old men. I have no clue whether Modi knew this or what he thought about it. But evident to any who could see was the solemnity of this event. Modi appears to sense it; his folded hands do not so much return people’s greetings as much as they acknowledge and accept the Ashirwad. Why the verse and why the Ashirwad? I seek neither the motives nor an explanation here but something else.

To begin with, it must be a description of an event that tells us what makes old men come to the streets to give Ashirwad to a politician, a Prime Minister, for finding their ‘lost’ would-be King. A king is a paradigmatic political function. So is the prime minister of a country. Were the people lining the street unaware of this? No, they were aware of the political nature of the event. Why sing a verse from the Ramayana, a story of kings, otherwise? If their Ashirwad was to Modi, a human being, a Gujarati, or an individual person, they could have chanted more suitable verses crafted for such an act. Yet, they did not. Without orchestration by a spin-doctor, they chose a verse from an epic about politics. The old men on the pavement, one could say, were religious, and perhaps, even deeply so (Sri Vaishnavas, probably). Their raised hands were not signaling political messages, like the Hitler Salute, for example. As Ashirwads, their primary place is in ceremonies and festivals expressing the ‘religious’; streets and motorcades do not attract them. These were not the blessings of a Pontiff directed at the believers thronging the streets either. The people in the streets of Srirangam were Hindus, true, but cannot be seen as followers of the RSS or the BJP even if some of them were. Yet, all recognised a political event, celebrated the return of a king, and gave their Ashirwad to a politician. As though that was not enough, they sang a verse about the king. In short, yes, politics entered daily life, but it did so with the full knowledge of the actors and not as an interference in a ‘religious event’, whether it is taking a ritual dip in the sea or raising hands in Ashirwad. ‘Religion’ mixed with politics, yes. In the streets of Srirangam, ‘the religious’ became what it is because it was adorned by politics even if there was no political conductor making the choir sing a political verse.

I speak of Srirangam because what happened there happened in Ayodhya as well. Politics did mingle with ‘religion’ and this was so experienced by every Hindu (if not every Indian). When people resonated to the Ayodhya event, responded to it in an astonishing way, that did not indicate either acceptance or acquiescence of a people to the BJP or the RSS propaganda. It is not their “positive” talks about Hindus that motivates people but the event. This event can never be “purely religious” as our tatvadarshis wish nor is it an admixture of politics and religion making both impure. What am I trying to say?

In the intellectual world we inhabit, the sacred and the profane, religion and the secular, are intrinsically different realms because God and the world are separate from each other. If I am allowed the use of the plural, I would say that the world of the gods is not and cannot be the world of men. The Creator and His creations are separated realms in ways that make God’s intervention in our world, the interference of God in the affairs of Human beings, into an exceptional event. Islam does not allow such interventions but both Judaism and Christianity need them. Without the covenant with Yahweh, there is no nation of Israel; before being led into the promised land, the Jews were strangers or slaves elsewhere. Without the Messiah, there is no Christianity; nor is there any hope for salvation or atonement of sins. Even if God is outside time and space, Semitic religions insist that He created the Cosmos we live in that is located in time and space. Whether God is humanly accessible or not, whether He intervenes in the world or not, the realms do not meet or mingle. If we attempt mixing these, the world becomes impure, and we blaspheme. Human history records the results of trying to add religion to politics, law to religion, or religion to human affairs. Derived from an exegesis of the gospel of Luke, the story of the two swords (the material and the spiritual) is both long and tragic. It is about who should wield these swords, the Pope or the Emperor? Whatever the answer, this much is clear: mixing religion and politics has led to strife, pain and human suffering. While this is true, this story could become our story if and only if there is an absolute ontological separation between our world on the one hand and what makes us into “God’s people”, namely religion, on the other.

Sheldon Pollock, a respected Sanskritist-cum-Indologist, wrote a book some time ago bearing the title, The Language of the Gods in the World of Men. In one sense, if we think of Hebrew and the tower of Babel, the title is appropriate. In another sense, it suggests an incomplete thought because, among other things, the book is about Sanskrit, the “devabhasha”, and India. Here, we need a different train of thought: devabhasha can exist in the human world if and only if either the Gods live in the human world or the other way round. I am not suggesting that Indians see the world as ‘sacred’. The Bible too would agree here because God’s creations are sacred. They sing His Glory. But I suggest what is a trivial piece of knowledge to all Hindus if not all Indians: whatever exists has existence only in this world (Jagat, Vishwa) because there is nothing outside this. The Gods may have their own worlds but these are located in the Vishwa. The world or the jagat encompasses all that was, is, and shall be. Nothing is far enough in space nor too distant in time to have no existence in our cosmos. Were this not to be the case, we could never access the Gods because nothing outside this world is accessible. The human and the divine conduct their affairs in this world and, of necessity, there will be interactions in this single vishwa between the two mini-worlds. We might know nothing about the nature of these mini-worlds or the lokas of Gods; we might not know details and specifics of the hows and whys of these interactions. It might even be the case that the gods are not there at all and that their worlds have no existence. Whatever the case, we do know there are no separate realms of existence, speaking ontologically. We and the gods exist together if they too exist.

Thus, our question becomes: what is politics in such a world? If politics is about human affairs, what exactly are these affairs? Do they exclude the gods and, if we tried to do so, could we succeed in excluding them? Who or what can direct and steer the gods if their affairs include interfering in human affairs? The issue is not about whether you think Ganesha or Kali exist somewhere in the cosmos, on some unexplored planet or in an unknown galaxy. It is this: in this culture, working within the circumscription of the framework pointed out, how would people think about politics? Surely, our ancestors did think about politics; they also formulated some questions and answers about social and human existence.

It is important to notice the focus and the scope of my claims: the assertion is not that the ancient Indians have answered or even could address problems of our 21st century world. But I do believe that the way they formulated issues and the lines they sketched in pursuing their enquiries are needed today. Living in a world that did not know an ontological separation between religion and politics, our ancients formulated questions about politics. Even though our world is the same as the one they lived in, the languages we use, and the conceptual frameworks embedded in these languages differ. We do not know their questions; we do not see the world we share with them; we pontificate about secularism when we have no clues about what religion is or even what it does; idol worship, the holy, consecration, etc., do not belong in our world which is why we cannot identify them. If we want to talk about the affairs in this world, should we not try to find out how our ancestors thought and talked before there ever was a Locke or a Mill or a Rawls? We should, I think.

This understanding of the world implies an interesting understanding of politics that is different from what we have so far been fed with. Our understanding of what politics is, the nature of our political practices (to the extent they depend on what we think politics to be), would then become different from what we know about either of the two today. We could assume that politics has to do with governance. But the what and the how of this governance would then be investigated differently.

What happened in Ayodhya is an expression of this different awareness, something which resonates deeply with what is alive in our culture. Modi signalled this difference while speaking of a new age and in trying to draw a contrast between history and the past. We might want to heap insults on him, draw on third-rate political psychology to sketch his personality, and do ‘comparative politics’ by bringing Putin, Trump, and Erdogan into the picture. Such activities might endear us to some while irritating others at the same time. Trolls might even love us because it would encourage trolling. However, if we focus only on this, we will miss this crucial insight: the psychology of an individual is deeply influenced by the cultural psychology of a people. In turn, it impacts social psychology as well. The intellectual poverty of both these domains in western thought can only be appreciated by those who appreciate the richness and sophistication of Indian thinking in these areas even when they are millennia old.

The third reference point is also about politics which expands the previous thread. It does so differently, by partially outlining the task facing us. There are two players in this act but it revolves around Ram Lalla, the prince child currently resting in the palace.

Mehta puts the issue this way: “Prime Minister Narendra Modi (is) now donning the mantle of Hindu kingship…” Well, here is what a Hindu might say in reply: with the pran pratishtha, Rama has been brought back to the palace. He is around five years old now and must grow up to become an adult before embarking on building his kingdom, the Rama Rajya. Because he is still a child, he cannot immediately ascend the throne to rule the kingdom. Currently, the Amatya or the Maha Mantri stands behind the empty throne advising when needed, serving the land and the throne in the name of the would-be-King. He serves but does not rule, which is perhaps why he calls himself a pradhana sevak. Whatever their moral character, such political figures are known to us as the regents. In any case, this Maha Mantri can “don the mantle of kingship” if and only if he usurps the throne but not otherwise. Only as the usurper would he become the king. The question is obvious: apart from acquiring the title of ‘consecration’, does the Ayodhya pran pratishta celebrate usurpation as well? Why would anyone (however duplicitous) bring the rightful heir back to the palace, seat him next to the empty throne in the royal court, only to don the mantle of kingship thereafter? Is this “the election steal” that the US knows so much about?

In any case, for the young prince to grow up and build his Kingdom, he must receive the required education that makes him fit to rule and be a king. This requires that he is formed, groomed, and is imparted knowledge. He must learn many skills as well. To be fit for the throne that is currently empty, the prince needs a teacher. Not anyone can “don this mantle”: such a person must deserve to be a rajaguru, the one who teaches the prince to become a king. The problem, of course, is: where and how is this person to be found?

To begin with, the Maha Mantri should seek such a figure now. Playing the regent and standing behind the empty throne also gives him this responsibility. It is an imperative, an onerous but an extremely urgent and important duty. He is the first of the two players.

We are the second players. As intellectuals, we must produce knowledge. Chanting western mantras has not helped so far: the fifty-fifth genealogy of the original contract, the thousandth commentary on Plato’s Republic or Locke’s Two Treatises, or the millionth hurrah song on constitutional democracy are of no use. Our culture provides the heuristics required to think creatively, productively, and originally. We have inherited interesting questions and the ability to think through them. We can make the required alterations and modifications, developments, and enlargements, as we proceed. We can sketch alternatives to what there is because without robust theories in place we cannot end our mindless mimicry. “Alternative theories in politics” is neither a slogan nor a joke. This requires creating alternatives to enormously rich theories, sophisticated practices, and complex institutions that have been with us for more than 3000 years. No individual, or group, or even a generation could possibly accomplish such a mammoth task.

Yet, the task remains ours. Knowledge is needed when only ignorance rules. We cannot palm off vague slogans as new and interesting knowledge because we do not confront toddlers. As in old days when learned people came together to endow the titles of Brahmasri, our western colleagues will test our mettle today. They will judge, umpire, and referee because our public is not entirely or only Indian.

We face many dangers here because our society ceaselessly incentivises mimics, grows parasites while stimulating and rewarding salesmen who sell snake-oil. Still, the young prince, Rama, patiently awaits his Rajaguru. Such a person can only come from those in whose hearts Saraswati has a permanent abode. It is possible, only just possible, that the Ayodhya event indeed portends the beginning of this age, the Indian Pratyabhijnana.

This is the third and final part of Prof SN Balagangadhara’s analysis of media reportage and commentary on the Ram Temple event in Ayodhya on 22 January this year. Part 1 can be found here, and part 2 here.

SN Balagangadhara is a professor at the Ghent University in Belgium