Culture

How Can 'Bhaktha Samajams' Envisaged In Telugu States Play A Role In Temple Governance

Vivek Rallabandi

Nov 05, 2025, 10:28 AM | Updated 10:34 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The demand to free Hindu temples from government control has become a cause célèbre among Hindu organisations and many ordinary Hindus. Many a conversation about the state of Bharat today veers towards the plight of Hindu temples controlled by secular administrations. There is a constant stream of news about the corruption and mismanagement that plagues state-controlled temples.

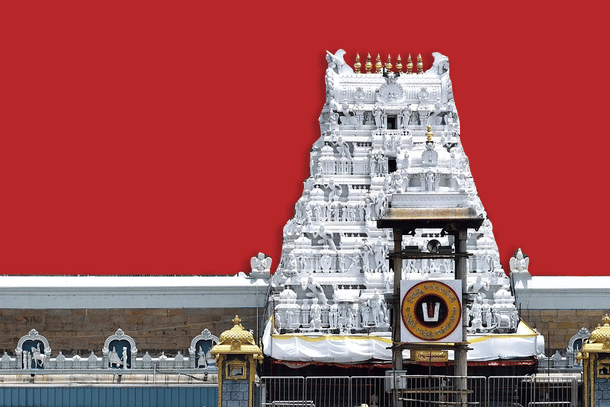

In the last few weeks, the Kerala High Court has ordered an inquiry into the pilferage of gold used to plate murtis of dvarapalakas at the famed Sabarimala shrine, managed by the government-controlled Travancore Devaswom Board. Similarly, the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams in Andhra Pradesh have been rocked by recently resurfaced allegations that crores of rupees were stolen by a temple servant from the hundi. These allegations are only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the issues that bedevil state-controlled temples.

As a recent Swarajya column highlighted, major temples across India are becoming increasingly commercialised, causing immense suffering to devotees who visit them with deep reverence and belief.

Despite the many troubling elements that state control of temples involves, not the least of which is the fundamental question of why secular governments should selectively be managing religious institutions, freeing them from government control en masse does not seem to be on the cards in the short term. Simply put, the political will to effectuate such a move does not exist, particularly in South India, where most major temples are government-run.

Furthermore, the legal effort to liberate temples from government control hit an impasse earlier this year. Considering a 2012 petition filed by the late Swami Dayananda Saraswati of Arsha Vidya Gurukulam in Tamil Nadu and others to declare Hindu religious endowments acts in several southern states unconstitutional, the Supreme Court relegated the petitioners to argue their cases in each state’s High Court individually. Thus, it is safe to say that, in the immediate term, the government will continue to manage Hindu temples.

Naturally, our inquiry must then shift to understanding the most effective course of action to address the aforementioned issues in the immediate term. After all, the steady drip of allegations and even the fundamental ignominy of having our sacred spaces controlled by a secular (and sometimes brazenly anti-Hindu) administration are enough to shake the conscience of any Hindu devotee.

Temple activists such as T.R. Ramesh of Tamil Nadu are taking the battle to the courts, ensuring that state endowments departments are held to account for their illegal actions. But what is the role of the common devotee? What can they do to safeguard their local temple and ensure its sanctity?

In a 2021 X post, T.R. Ramesh himself answered this question succinctly with the following advice: “Form local Worshippers Groups around each temple. You will then learn inability changes into Hindu power overnight. Do it.” Ramesh’s proposal is quite remarkable in two ways:

First, it sets up something akin to a shadow cabinet to parallel the temple’s secular administration.

Second, it creates a sense of investment and ownership among Hindu devotees in their local temple.

Groups of devotees can come together not only to partake in shared bhakti but also to discuss and critically evaluate temple governance decisions. Such discussion and collaboration would certainly give rise to the unmistakable conviction among devotees that they can themselves, without government assistance, administer their own religious institutions.

At first glance, such a model may seem aspirational to implement at temples at the macro level at temples both large and small, across districts and states. However, in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, there is a legislative mandate for the Executive Officers and trustees of each Endowments Department-controlled temple to establish and facilitate Bhaktha Samajams, or devotee associations.

In 2007, the Congress government of then-undivided Andhra Pradesh, helmed by Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy, made several amendments to the Andhra Pradesh Charitable and Hindu Religious Institutions and Endowments Act, 1987, including the provision creating Bhaktha Samajams.

The overall thrust of the amendments was to democratise temple governance and improve its efficiency. For instance, one of the amendments created the Andhra Pradesh Dharmika Parishad, a “semi-autonomous apex body” consisting, among others, of senior Endowments Department officials, mathadhipatis, a retired High Court judge, temple philanthropists, and agama scholars.

According to a select legislative committee report on the amendments, the Dharmika Parishad would ensure that “the rich traditions and the cultural heritage are preserved and all stakeholders participate in a spirit of partnership with devotion and dedication to bring Temples back into social life as centres of moral education, human welfare, fine arts, and architecture.”

Another of the amendments exempted certain temples with low annual revenue from being managed by an Executive Officer from the Endowments Department, which would encourage local self-governance. These amendments are also part of the Telangana Endowments Act, which applies to the state of Telangana after the Telugu states were bifurcated in 2014.

The legislative report noted that the provisions regarding Bhaktha Samajams were included “as a reminder that temples must forge partnerships with devotees to turn temples into vibrant centres of cultural renaissance.” The specific provisions in the 2007 legislation are included below:

Section 24(4): It shall be the duty of the Trustees of every temple to foster faith, devotion and ethical conduct in society by facilitating formation of a Bhaktha Samajam attached to each temple, on a voluntary basis, consisting of the devotees thereof in order to periodically organise Bhajans, religious discourses, devotional and other religious programmes such as nagara sankeertanas etc., appropriate to the custom, usage, tradition and sampradayams of the temple concerned. It shall be competent for the Commissioner, with the approval of the Dharmika Parishad, to frame bye-laws for the constitution and functioning of the Bhaktha Samajams.

Section 29(3)(e): It shall be the duty of the Executive Officer of every Religious or Charitable Institution to foster faith, devotion and ethical conduct in society by facilitating formation of a Bhaktha Samajam attached to each Institution, on a voluntary basis, consisting of the devotees thereof in order to periodically organise Bhajans, religious discourses, devotional and other Religious programmes such as Nagara Sankeertans etc., appropriate to the Custom, Usage, Tradition and Sampradayams of the Institution concerned.

The legislation envisaged the establishment of Bhaktha Samajams at each Endowments-managed temple and specifically tasked the Executive Officer and trustees of each such temple with facilitating the creation and orderly operation of such Bhaktha Samajams. Clearly, the legislature recognised temples’ role as dharmic ecosystems and opined that devotees’ participation in their affairs was indispensable.

As such, Bhaktha Samajams were conceptualised as vehicles to give devotees a seat at the table in terms of planning and organising various dharmic activities at temples. In effect, the Bhaktha Samajam designates ordinary devotees as recognised stakeholders in the temple’s affairs and vests them with a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the temple. Furthermore, by planning religious events and discourses, the devotees that make up temple Bhaktha Samajams can ensure that temple funds are spent on the dharmic activities for which they are intended.

Though the legislation limits the Bhaktha Samajams’ ambit to planning and executing religious events and bhajans, this is, in the larger context of temple governance, still quite powerful. When Hindu devotees of each temple, both large and small, come together in pursuit of shared ideals of bhakti and dharma, they inevitably become invested in the temple’s affairs.

When elements of corruption or mismanagement in the temple’s affairs come to their attention, the Bhaktha Samajam provides them with a statutorily recognised platform and a united voice to speak up. This is particularly significant considering that, in many cases, temple trust boards are composed of politically connected figures, a practice that the Supreme Court has flagged.

As such, Bhaktha Samajams can serve as a “shadow trust board” of sorts by representing the true interests of ordinary devotees and by serving as a bulwark against decisions inimical to devotees, such as exorbitant seva rate hikes.

In this way, Bhaktha Samajams can play a valuable role as a first line of defence on the ground against malpractices in temples. Ultimately, if Bhaktha Samajams are established in temples across the Telugu states, as the legislation prescribes, they may well give rise to a common resolve among Hindu devotees that they can collectively manage their own religious institutions without government interference. In this way, Bhaktha Samajams can be precursors to a larger objective of temple freedom by fostering the political will for such a move among the masses.

Of course, the potential of Bhaktha Samajams can only be realised when they are actually implemented as prescribed by the Andhra Pradesh and Telangana Endowments Acts. Unfortunately, despite a clear legislative mandate, there is no Bhaktha Samajam in operation in the vast majority of Endowments-controlled temples in both Telugu states. It is incumbent upon temple devotees across the Telugu states to demand that the Executive Officer and Trustees of their local temples fulfil their statutory duties and constitute a Bhaktha Samajam at the earliest.

Technology has also advanced significantly since Bhaktha Samajams were statutorily promulgated in 2007, and these advances can help them function even more effectively.

For instance, devotees can use WhatsApp (or Arattai, a home-grown alternative) groups to fix meeting times and plan upcoming events. QR codes to join the group can be displayed in the temple premises for interested devotees. Likewise, for major temples that have a large contingent of devotees who do not live in close proximity to the shrine but visit regularly, virtual Bhaktha Samajam meetings can enable increased devotee participation.

In short, Bhaktha Samajams can be a valuable step forward in democratising temple governance in the Telugu states and beyond by providing a model for how devotees can effectively and meaningfully partake in the running of their sacred spaces.