Culture

Ilaiyaraaja: A Life Of Syncopated Symphony

K Balakumar

Mar 03, 2025, 12:18 PM | Updated 04:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The recent round of interviews that Ilaiyaraaja gave to chosen media houses, as some kind of curtain-raiser ahead of his much-expected Symphony to be performed in London on March 8, was fascinating to follow, mainly for the one question that went unasked.

Now, the prolific Raja — as he is mostly called — is a difficult man to do interviews with, mostly because he consistently operates at a plane far higher than the rest of us can even think of. Most of the questions any interviewer can come up with will look monumentally silly in front of that man. Also, he is well known for his proclivity to not suffer fools with any amount of levity, and his blunt ways are often misconstrued for hubris. Of course, like most other things, this too doesn't bother the great man as all his life his sole focus has been just producing sterling music.

So, like most other interviews with him, the latest ones too did not offer anything new, except when Raja chose to divulge a nugget of musical insight with his casual brilliance. At one point in one of the interviews, he just played a small random chord on his trusted soulmate harmonium, and said (paraphrased): "this is harmony, can you hear it?" The larger point that he was driving at was that harmony need not be a multitude of instruments playing variegated tunes simultaneously. One man hunched over a harmonium can deliver it. Music is that simple. Music is that great.

The interviewers, sadly, did not seem to have done their homework on symphonies and their rich traditions, and, in the event, it was a tad disappointing to see them ask Raja what a symphony is. Not knowing what makes a symphony is not a crime. But to pose that question to a composer who operates at rarefied musical heights is. It is like buttonholing, we don't know, Einstein on what a quadratic equation is.

It has to be admitted that in a country which doesn't have any discernible tradition in western classical music, to keep a conversation on that subject that would still connect to the lay viewer can be a tough exercise. But the one question that could have brought about some context was never raised: Raja's own previous symphony that was never released to the public.

The symphony that went silent

Of course, his die-hard fans will remember this event that proved to be eventually anticlimactic. But for the most in the mainstream, this is lost in the mists of time.

This symphony that was not-to-be, recorded with the famed London Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of conductor John Scott in 1993, was then touted to be the first one by an Asian composer. The news of Raja recording an unnamed symphony (Fantasy was one of the names mooted that Raja, however, did not find apt) in London was a rage in Tamil Nadu at that time, and his arrival back home post the recording was on par with the ones given to World Cup-winning Indian cricket teams.

Many musicians, including the Carnatic legend Mandolin Srinivas and Raja's (Carnatic) guru T V Gopalakrishnan, were among the many celebrities who received him ceremoniously at the Madras airport. Even the conservative old-guard of Carnatic music Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer dropped in at Raja's house to congratulate him on a pioneering musical achievement. It was thought to be that seminal.

Not to be left behind, Kollywood unveiled a mega programme to honour a true GOAT. It was on that night of carnival that Raja was handed the title 'Maestro', a monicker that is now glued to him seamlessly.

But the recording which was to be formally released a bit later never happened. Days, months, and even years passed, but it never emerged from the thickets of mystery that had grown around it. Plenty of conspiracy theories, inevitably, began to do the rounds. Many of them were decidedly uncharitable to Raja. But the man at the centre of it all was never really bothered by all the innuendoes and poisoned rumours swirling around. It is not his type to respond to critics and calumny.

Anyway, much later, as the internet arrived, one of the fans managed to reach out to John Scott on his web page to set at rest the various misgivings centring on the sidelined symphony, and the conductor responded saying that he tried to encourage him (Raja) to get his symphony released. "I believe he was hurt by a critics review, and this is the reason it has not been released."

And he added: "The trouble is that critics are capable of destroying sensitive artists and have done it throughout the history of music. The more one knows a piece of music the more one loves it, and the stupid critics are incapable of judging anything they have never heard before."

The internet, especially the sub-reddit forums, are full of speculation on who this critic is and what he had said for Raja to hold back his much discussed symphony in the 90s. It is irrelevant now, but it starkly underlines that when it comes to artistic sincerity and integrity, Raja practices it uncompromisingly and wouldn't mind pulling the plug on what was thought to be a dream-come-true project.

But when you are musically so rich and abundant, trashing to the recycle bin one piece of recording can be no big deal.

Symphony or just another piece of music?

This elaborate background is needed to show what Raja may actually be feeling about his upcoming Valiant performance at Eventim Apollo theatre in London. To be sure, he must be excited for the symphony, but it can be claimed that it would not be majorly different from the emotions that accompanied him in the creation of his thousands and thousands of songs that continue music fans in thrall for over 50 years now. For, his fidelity to his art is a constant. That is why he will approach, say, a Ramarajan song for a nondescript movie and a symphony to be performed among the high priests of art with the same skill and sincerity.

His razor-sharp mind doesn't differentiate between music. It is a strange kind of artistic agnosticism that only the truly great can summon. It is also why he is able to uncannily intersperse his every-day movie songs with eclectic elements of Carnatic, Hindustani, jazz, western classical styles and countless other genres in a way that is otherwise not normally possible. For instance, take his Ninaivo Oru Paravai in the film Sigappu Rojakkal — composed in 1978, just two years after his arrival in films.

The song situation is typical, a dreamy one like in almost every other movie in India, but Raja rather than just sit back with standard orchestration, fills it with riches that goes beyond the mundane remit of the movie. Right at the first interlude — interludes of a song, by the way, is where Raja luxuriously lives — Raja unleashes a string and brass combo that if elaborated well and truly wouldn't be out of place in a symphony. That he pulls this off in a dyed-in-the-wool cinematic melody without anyway sounding pretentious is the true hallmark of his mastery. Or take his Madai Thiranthu song (Nizhalgal, 1980) and see how he brings to the fore in the ludes the verve and zing similar to that of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Flight of the Bumblebee.

(It was also the song which had the famed Vaali line that declaims: ‘As I make new tunes, I too am God’ (Pudhu ragam padaipathale naanum iraivane), and the newly-minted Raja had the staggering chutzpah to have that specific portion of the song shot on himself).

In Raja, the Carnatic and western classical musician reside simultaneously

These two songs, in the early days of what has panned out to be a remarkable career, make it clear that western classical sensibilities are not newly-acquired but something that had been his constant companion from the start. And over the years, he has established there is none even close to him in churning out extraordinarily unique songs in which Indian melodic structure and the harmonic chord progression of western vintage reside blissfully together. It takes genius effort to accomplish this, but the usage of the word genius somehow seems lazy in Raja's context as it looks a lazy placeholder for everything that has been magically effected in his music. It needs deeper understanding and appreciation of someone who is not only deeply aware of the Carnatic and Hindustani musical ethos but is also equally adept at western classical style.

And his embracing of western classical concepts is not mechanical or theoretical. The way western harmonies flow in his compositions, how those beguiling chords progress show that here is a musician who has actually managed to make the impossible twain meet. The segue of western chords into the main Indian melody in his songs is the veritable definition of, well, happy marriage.

The way he composes, performs and records his music in themselves shine light on the unique style residing in him. He thinks up Indian music, any musical improvisation or invention happens within his head, he writes them all in western notation, and the singers and instrumentalists have to perform them without even a single note changed or out of place. Such a stentorian style also makes him the rightful quintessential Indian musician candidate to have a go at the fundamentally ordered western classical music.

How Raja happened?

How did this confluence happen in a man from one of the remote villages of southern Tamil Nadu?

There is a delightful interview of that tuneful singer SP Balasubramaniam in which he says that Raja, right when he had just come to Madras from his hinterland Pannaiyapuram, could squeeze out Lara's theme (from Dr Zhivago) on his rickety harmonium. SPB's suggestion was that there was something preternatural to a village lad, with no real exposure to international music, belting out western tunes almost with impish insouciance.

Without meaning to contradict SPB, who had been a friend of Raja's right from his pre-movie days, Raja is not an inexplicable talent. But more a consummate result of inspired hard work married to astounding creativity. Raja's western classical music ideas did not arrive on the wings of a benevolent fairy. They were instead a gift to him for the hours and hours he spent listening and internalising the works of, say, Bach, Beethoven, Mozart when he was apprenticing under Dhanraj Master.

Raja has recorded in his memoir that when he was learning western music from Dhanraj he had the opportunity to come across the vinyl records of the great western composers, and Dhanraj also had the propensity to keep reverentially invoking the names of the Western masters. It was inevitable that the young Raja, who was desperate to internalise anything related to music at that point, also drank in these satisfying sips from the western bottle.

That is why during one of the interviews Raja was able to rhetorically say with cavalier confidence that had he not written those harmony lines would the fans be knowing about Bach, Beethoven or Mozart! The critics saw arrogance dripping in this line. But it also conveyed the truth that those impossible ludes did not happen by themselves. The man was more than mindful of what he had dished out. WCM had gotten hold of that precocious village youngster then itself.

It was practised preternaturalism, if you will.

India and Western Symphonies

Of course Raja was not the first Indian music director to be impacted by western symphonic ideas. Many stalwarts before him had dabbled with similar themes. In fact, it is argued in certain academic sections that early Bollywood music, because of the easy availability of English musicians (remnants of the retreating regime) had willy-nilly western ideas as instrumentation was mostly done by them (Brits).

If anything, much before that, Indian rulers during the British time here became interested and invested in Western classical music. It is said that King Serfoji II of Thanjavur (1774-1832) encountered selections from Handel’s Messiah, Judas Maccabeus, Esther and his Coronation Anthem at a concert in Madras in 1794.

He was so impressed that he reportedly set up his own wind band trained by a British bandmaster to play in processions and at the royal court. In the neighbouring Mysore, Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV (1894–1940) had an orchestra named, The Royal Carnatic Orchestra. His successor Maharaja Jayachamaraja Wadiyar (1940-1971) was a concert pianist and was the first president of the Philharmonia Concert Society in London in 1948 and funded the Philharmonia Orchestra too.

But these were mostly cultivated tastes and aberrations, and the hold of Indian traditional music was so much that Bollywood and other Indian film industries did not truly embrace the western classical music motifs, save for occasional flourishes in, say, by that extraordinarily gifted Salil Chowdhury, who was the one prior to Raja, who organically imbibed the nuances of both Western and Indian classical music, and his cinematic output was imbued with a certain aesthetic that was a comfortable mix of the two.

Many music aficionados have written about how Salil da loved and drew inspiration from the legendary Frédéric Chopin. Raton Ke Saye in Annadata (1972), in the haunting voice of Lata, is in its flow had the flourish of the Polish composer.

WCM and Indian ads

Of course, Salil da most famously Indianised, as it were, Mozart's 40th Symphony in G Minor as Itna Na Mujhse Tu Pyar Badha in Chhaya (1961).

Before Salil da and after Salil da, the western symphonic ludes, which broadly meant grandstanding the usage of multitude of various types of violins and flutes, were merely a musical ruse to invoke the idea of western sophistication & suave style on screen.

Examples from the Indian ad world to plug the concept of 'classy' through classical music are numerous. The most well-known is without doubt the iconic infusion of Mozart’s Symphony No 25 in Titan ads. Then Raymond – The Complete Man's ad fell back on Schumann’s piano piece Traumerei. while Hyundai's now discontinued Sonata car ad was based on the Piano Sonata by Mozart.

Interestingly, the Mozart Symphony No 25 in G minor was also the muse for Feluda theme of Satyajit Ray, who among the Indian film directors was intrinsically influenced by western classical music that he himself composed and put to use sonata, fugue, and rondo for his movies. That was his passion for that kind of music.

Ray employed western musical bits without bothering or needing to indigenous them, while Salil Da showed his touch in using the grand movement in Mozart's composition as the take-off for an Indian melodic tune. This kind of reimagination needs careful skill, and is not a bargain basement copy-paste effort, and some critics even saw Hindustani Bhairavi loosely incorporated into the tune. That was Salil da's greatness and his humility to understand the larger picture that his music was only in service of the movie he was part of.

Raga and WCM fusion, an uncomfortable combo

Western and Indian musical philosophies diverge almost at a physical level itself as one prefers to perform sitting, while the other standing. Also, the tuning of the violins in themselves are different. Indian violinists mostly have the instrument set to a specific raga's scale (like Pa, Sa, Pa, Sa) while Western instrumentalists are prone to use the standard tuning (E, A, D, G). This ensues in different results: Indian music, with its pronounced melodic emphasis, allows for seamless improvisation, while western style eventualises a structured, harmony-focused music.

Most attempts at fusioning the two have been almost always unconvincing. It is, as they say, neither one thing nor the other. This constant urge or proclivity to underpin western classical ideas with quintessential Indian musical tropes is attendant on almost all 'symphonic' attempts in Indian films. Why just Indian movies, even Indian instrumental masters like Pandit Ravi Shankar or violinist L Subrmaniam, who have tried their hands at symphonic music have always done so through the lattice of Indian classical raga-based music. It was reinvention for primarily Indian audiences, and hence they never made any great splash beyond Indian shores and Indian audience.

It was not just Indian musicians even the great Jewish composer Walter Kaufmann, who had under his belt six symphonies, eleven string quartets and more than a dozen operas, when he sought safety in India (he had to flee the Nazi Germany), chose to flavour his symphonic offerings with Indian inputs. Kaufman, who composed the All India Radio's legendary signature tune (slowly traipsing in Sivaranjani raga), was perhaps the first one to marry the two diverse classical styles of music before such fusion became more mainstream. He had to his credit pieces named: Madras Express, the Six Indian Miniatures and the Violin Concerto No 3. He also did many that applied the raga techniques.

Reading and writing music on paper not so common

Yet, despite the influence of Kaufman (he had also taught a young Zubin Mehta in Bombay) who also scored music for some pre-talkie Hindi movies, western symphonic sensibility never really took strong roots in Indian film musical setup mainly because of one fundamental issue: Most of the music directors don't (or can't) write their music on a sheet. Aside from the aesthetics, the core difference between Indian and western classical music is: The Indian style is to pass on musical ideas through memory and performance. Western symphonic traditions set store by written score that doesn't allow scope for ambiguity or interpretation. What you see (on the paper) is what you get.

The music composer in Indian movies context is mostly the conjurer of the melodic line, and not part of the orchestration. It is no surprise that, aside from Raja, those who weighed in their film music with western classical themes were the ones who knew how to write and read musical notations on a sheet of paper. Salil da was well versed in it. Pyarelal of Laxmikant-Pyarelal combo is another one who is well tuned into this kind of music and arrangement. In fact, he may be the first Indian music composer to have recorded and released symphonic pieces. The first one is for the BBC Concert Orchestra, and was titled Om Shivam (First) in A-Minor. The other was named Indian Summer, inevitably seasoned with Indian filmi condiments.

But Pyarelal's musical effort went unrecognised by the cognoscenti of the western classical world. And that is what Raja is attempting to change with his Valiant.

Raja’s previous stab at global music motifs

Raja is pretty much aware of the challenge ahead of him, as he summed up in his interviews. He knows that none of his film musical aesthetics should rear their head in his symphonic offering. Also, he is equally aware that his output should be, while adhering to the pristine traditions of western classical music and its famed forebears, must still sound different and appealing.

Raja's previous standalone offerings away from films, though high on symphonic ambitions, were still meant to satisfy the archetypal musical appetite of an Indian fan. 'How to Name It?' was his first stab at fusion in 1986 --- the time of his peak and prolific film days. He followed it with Nothing But Wind in 1988 that had the great Hariprasad Chaurasia accompany him. That he managed to conjure these albums up amidst his unrelenting film commitments was in itself a testimony to the constant rage of musical imagination inside him.

The albums, one with 10 and another with 5 different tracks, established Raja's fascination for Bach, Mozart, and the baroque and classical styles in general. I Met Bach In My House and Mozart I Love You clearly indicated the highly specific direction of his inspiration.

In the first album, the tracks were mostly Carnatic ragas over baroque harmonies and structure played by a string orchestra with occasional Carnatic percussion. ‘How To Name It?’ album was musically more consistent than ‘Nothing But Wind’ that was patchy if you were analysing it from the western classical music perspective. It was mainly due to the fact that the musicians had no major grasp of orchestral string playing and it showed up in clunky transitions between sections. Some western critics even suggested that it could also be due to poor-quality instruments.

Thiruvasagam, a musical tour de force

But both the albums, meant for Indian audiences whose exposure to western classical music was limited, were popular and still are a talking point in musical forums in these parts. Raja's next major go at western type orchestration was through his Thiruvasagam, an oratorio rendering of chosen hymns from the Shaivite bhakti poet Manikkavasagar's eponymous work. The album was often taken, by his fans, to be in lieu of Raja's earlier unreleased symphony. But though the orchestration, at a mainstream level, was symphonic in stature, the structure was decidedly not.

But Thiruvasagam, no doubt a musical tour de force, made it clear that as a musician, Raja was now even more comfortable and convincing in western traditions. And importantly, the six tracks in the album were performed by the Budapest Symphony Orchestra with whom he had struck a fine relationship thanks to his earlier collaboration for Kamal Haasan's Hey Ram! (2000) and the background score for Lajja (2001). Now, Raja had better hands to back him. And the sounds were more convincing.

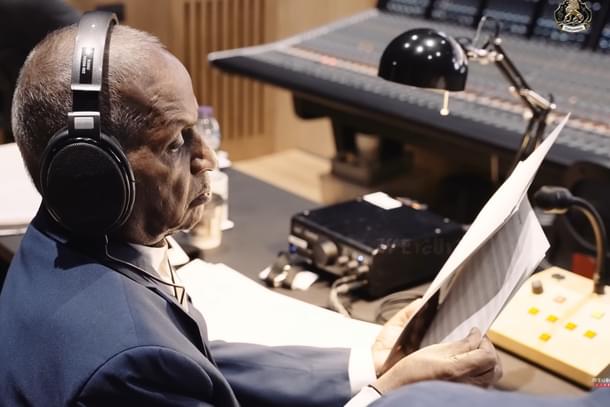

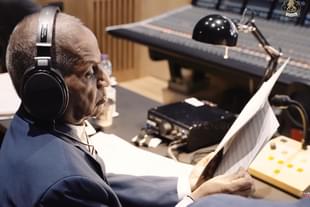

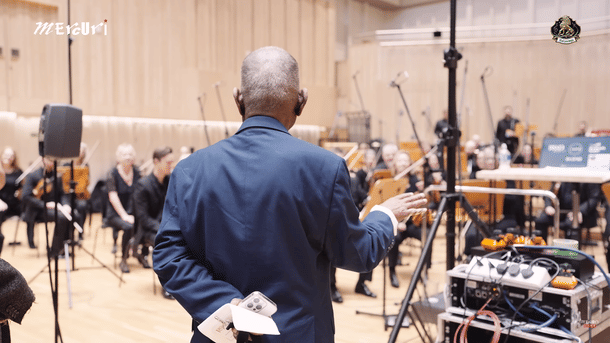

Since then Raja has had a few collaborative recordings with some orchestral teams in Europe, and for Valiant he has teamed up with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra --- the BTS video shows him recording enthusiastically with them. The concert on March 8, as per the promos, will have the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra performing.

Valiant, a journey into a new territory

Raja’s sense of history and a rare ability to place things in the larger musical context may have compelled to name his symphony Valiant as it is a determined and courageous musical effort going against the grain of what has been established in this country so far.

But make no mistake about it, Valiant may be a new territory. But howsoever it may turn out to be, it will bear his unmistakable stamp and definitely promises to be not a half-Indian and half-western hotchpotch. The previous experiences, and the responses to them, have made him wiser. His words confirm that. In the interview to The Hindu, he said, "I cannot allow room for the complaint that I have used the background score of a film song. The Indian element in me should not be a part of my symphony composing. If these elements are there, some might say that an Indian has composed." That is professionalism for you. And, mind you, he is 84.

The score for Valiant, with the standard 4 movements, he says, he wrote in 34 days. But it is actually a culmination of an improbable journey that began in the late 60s. A movement of early hesitancy but still filled with poise and promise, followed by years of smooth transition to greatness, leading to a period of sustained magical output and finally culminating in a crescendo of impossible virtuosity.

Irrespective of what happens on March 8, his valiant life, in essence, is already a syncopated symphony.