Culture

Seven Thousand Wonders Of India: An Artistic Pilgrimage Of India’s Lesser Known Temples-Part I

R Gopu

Jul 25, 2020, 01:29 PM | Updated 01:29 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

“Full many a gem of purest ray serene, the dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, and waste its sweetness in the desert air.”

-Thomas Gray, Elegy in a country churchyard

I recalled this poem, when I first visited Ellora, and gaped in sheer awe. The Kailasanatha temple is almost an entire hill carved into a single temple.

I knew there were cave temples, but not this wonder. A historian once said, “The eighth wonder of the world is that the Ellora Kailasanatha temple is not called the eighth wonder of the world.”

When a land has seven thousand wonders, is it perfidy to list merely seven?

We learn science and mathematics, history and geography, language, grammar, poetry, but we learn almost nothing of art , music, sculpture, in our schools.

The Sanksrit word kalaa represents art, craft and engineering. But in republican India, we have separated and compartmentalised these. Not a single engineered product, or building, reflects any Indian sensibility.

Our art whether in galleries, movies, advertisements, or public infrastructure, usually aspires to European notions – often utterly unaware and insensitive to a culture that spanned millenia.

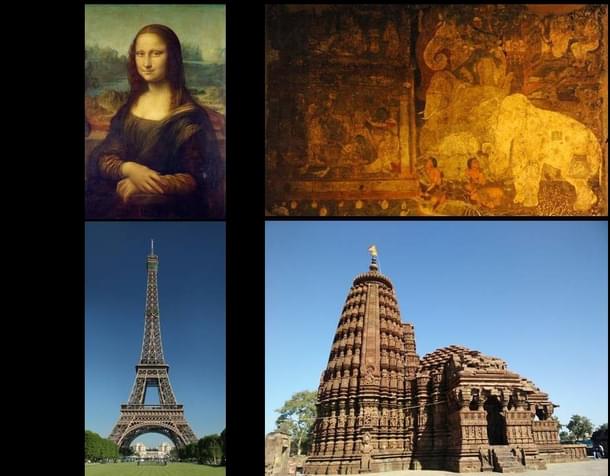

Here is a simple test (Image 1). On the left are a European painting and a tower. Can you identify them, and name the artist and engineers who conceived them? On the right are an Ajanta painting and a temple – can you identify them, their artist or the architect?

“Katrathu kai maNN aLavu, kallaathathu ulagu aLavu”, said the Tamil poet Avvaiyaar. What we have learnt (katrathu) is a handful (kai aLavu) of sand (maNN), our ignorance (kallaathathu) is as big(aLavu) as the world(ulagu).

With this series, I hope to introduce some lesser known temples, their sculptures, architecture, inscriptions, a vocabulary of art, a feel for the subtelty, nuance, bhava and rasa that transcends time and space.

Sculptures – shilpa nayanaabhiraama

Bhakti sometimes blinds us to art. I have seen people stand in line for an hour for a darshanam, then close their eyes in prayer when they finally reach the deity in the sanctum! Why?? Wasn’t the whole purpose darshanam – to see the murthy?

The wonderland of sculptures all around, invites equal apathy. Every sculpted pillar seems merely a support to lean on, a peg for a tube light or fan, or at worst, a receptacle to discard vibhuti or kumkumam.

Unless someone stops to stand and stare, and explain the sculpture. The change then, is electric. A small crowd gathers, curious to listen, eager to learn, grateful for any information, delighted and proud of their local wonder.

Classical Art

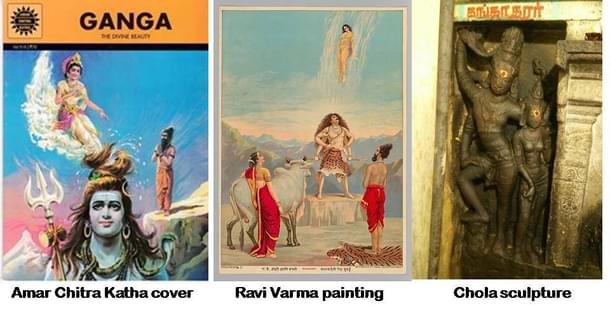

A Chola Gangadhara sculpture awakened to me to the subtlety of classical Indian art. I’ve read the Amar Chitra Katha version of Ganga, and illustrated stories. They show Ganga descending like a torrent or a waterfall, on the matted locks of Shiva.

Raja Ravi Varma’s nineteenth century painting depicts a similar theme. Parvati and Bhagiratha gaze, spectators like us.

But that is not how the Chola sculptor depicts this scene. Ganga tells Bhagiratha that only Siva can withstand the force of her descent from Devaloka. Bhagiratha performs penance to Siva, who grants Bhagiratha his boon. But Siva is aware of Ganga’s pride, that she will descend feet first on his head.

When Ganga reaches Bhuloka, he casually extends one strand of hair from his locks - and that is sufficient to withstand her tremendous force. Ganga flows into his matted locks and is trapped, unable to get out.

Bhagiratha performs another penance to Siva to release her… which he does. That single strand, stretched out to receive Ganga, is what the deeply learned Chola sculptors depicted. Parvati standing along her Lord, not across from him, twists her body away, as if jealous and angry of another woman touching her husband.

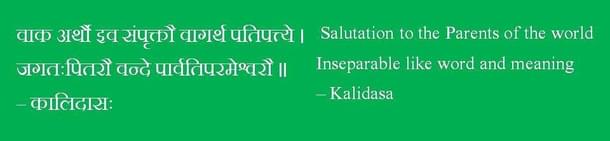

Parameshvara knows this is just her devaleela - divine play. So he gently but firmly holds Parvati’s shoulder. “Vaak-arthaa-iva-samprktau jagata-pitarau-vande” wrote Kalidasa, as the invocatory phrase of Raghuvamsham. Salutations (vande) to the Parents(pitarau) of all Creation(jagata), inseparable(samprktau) like(iva) word(vaak) and meaning(artha).

A thousand years ago, the Chola sculptor has captured the spirit of this description. At some time during a millennium, artists and rasikas lost this subtlety and classicism.

Compare this Chola sculpture with two predecessors. In the Pallava sculpture, Parvati’s body language may imply jealousy, but look at her face, she’s smiling gently and her face is twisting away from her body – her leela is a response to and reflection or a refraction, of Siva’s leela. Sookshma (Subtlety) governs bhaava (expression).

The Rashtrakuta sculptor chose complexity over subtlety, depicting (1) Ganga entering and (2) escaping Siva’s locks and (3) liberating Bhagiratha’s ancestors.

Three different time periods in one picture. The space for this sculpture is much larger, and hence its scope. Celestials are shown witnessing the grand event, and Bhagiratha watches, and his ancestors express gratitude.

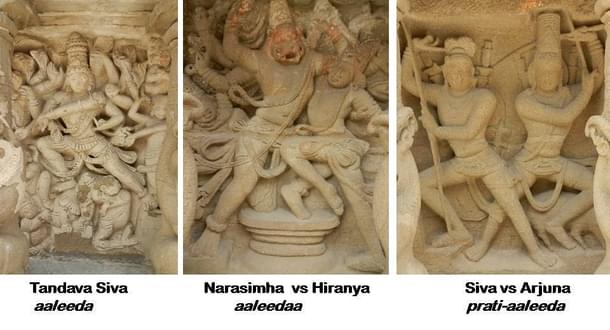

Shilpa Shaastras have much in common with Natya Shastra. The bhaava of sculptures reflect those of classical dancers. Each dance posture has several aspects – facial expression (mukha bhaava), stance (chaari), hand gesture(mudhra) etc. So do battle postures.

You can see these in the Sculptures in the Kanchipuram Kailasanatha temple. Siva’s stance in this Tandava is called aleeda. Narasimha and Hiranya are battling, not dancing, their arms and legs locked together. Their stance is also aaleeda. In contrast, in the Kirataarjuniyam sculpture, Siva and Arjuna, are in a different battle stance, called prathi-aaleeda (reverse aaleeda).

By contrast, several Mahabharata battle scenes are depicted in this Ellora sculpture: archers on foot, archers in chariots, hand to hand combat, sword fights etc. No suggestion here, unlike the Kiratarjuniyam sculpture – all action is depicted.

Vocabulary of art - Chitram, chitraardham, chitraabhaasam

Today we think chitram means painting, but in the shilpa shaastraas, chitram means a full sculpture, in the round.

Chitraardham, which means half-sculpture, is the term for a sculpture on a wall, a pillar or some such surface, where only part of the sculpture is etched.

Chtira-aabhaasam is the term for a painting. The sculptures we have seen so far are chitraardham.

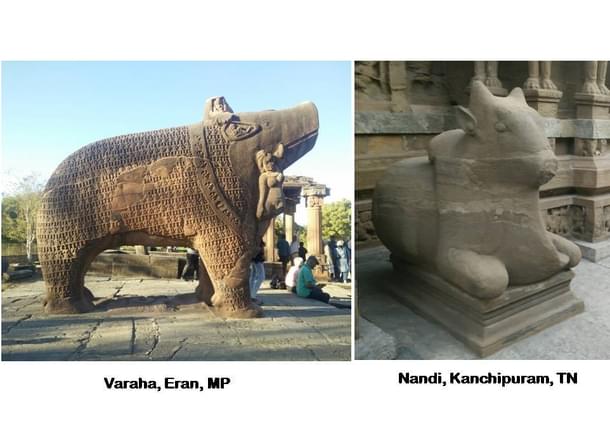

Examples of chitram are Varaha of Eran, the lion and elephant of Mamallapuram, Nandis in Siva temples, the and most images of deities in the main sanctum of a temple.

Chitraardham in walls, pillars, ceilings and roofs come in a bewildering but enchanting cornucopia of size, theme, intricacy, imagination and variety.

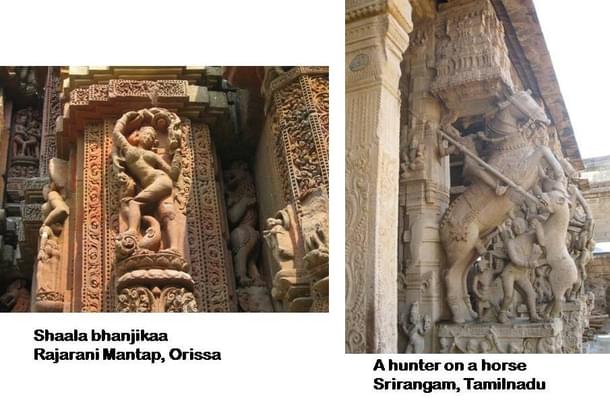

Shaala bhanjika-s, beautiful women, gracefully twisting in atibhanga while holding on to a branch are common in nagari temples. Horse-riders on a hunt and village dancers are found in Dravidian temple pillars.

Three Postures

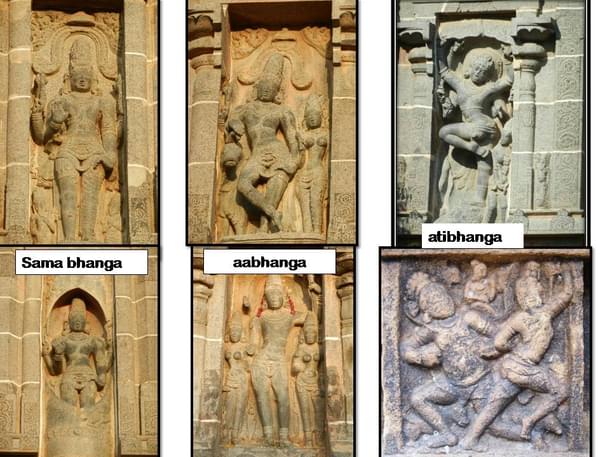

Sculptures are depicted in one of three postures.

1. Samabhanga - A sculpture may be symmetric along either its vertical or horizontal axis. This is the usual pose of the main deity in a sanctum, whose hand is in a gesture (mudhra) bestowing a boon or granting refuge.

2. Aabhanga - A sculpture that has a few graceful bends, holding a natural and casual pose, rather than a stiff symmetry.

3. Atibhanga - A sculpture that has extreme bends, capturing figures in moment as of extraordinary vigour, movement, ferocity, action

We don’t need to know these technical terms to enjoy art. But knowing a vocabulary is the first step to develop taste, aesthetics, and discernment, and an Indian ethos.

Portraits and Narratives

The sculptures demonstrating these postures are portraits : they capture a moment. Portrait sculptures are idols for worship. Koshta murthis (niche sculptures) on walls or pillars, are usually portraits. But sometimes a single sculpture or a series can narrate a story, capturing several events.

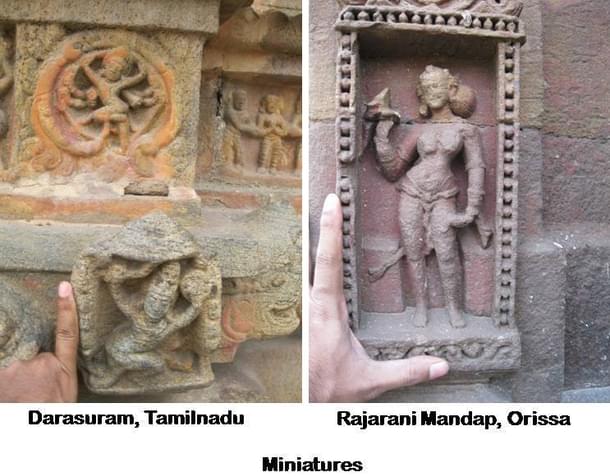

Large grand sculptures like Sadashiva in Elephanta, Arjuna’s penance in Mamallapuram, Bahubali in Shravanabelagola capture our attention. But some of the most marvelous art is depicted in miniature sculptures, that we rarely notice.

The most common miniature sculptures are decorative. Lotus patterns, rows of swans, elephants, horses, yaalis, bhutaganas, flowers, dancers, musicians embellish segments of walls and pillars. Intricate miniatures in Hoysala temples in Belur and Halebidu, and in temples of Rajasthan are famous.

Their intricacy and delicacy are possible because they are in soapstone and marble, respectively, which are softer stones than granite(Tamilnadu) or basalt (Maharashtra).

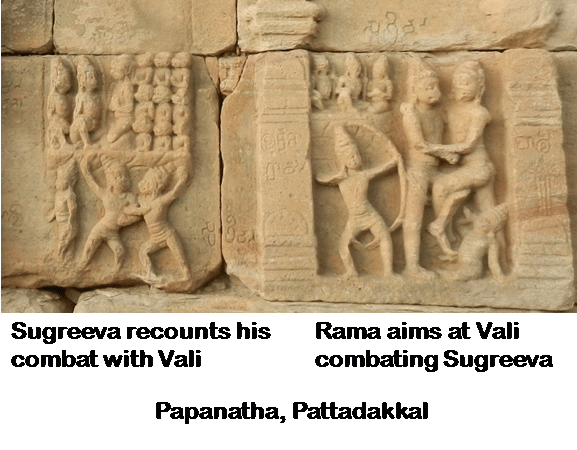

Some miniatures are part of an entire narrative sequence. Ramayana and Mahabharata are the most popular themes. The battle scenes in Ellora are part of such a series. These two from Papanatha temple in Pattadakal, feature two combats between Vali and Sugreeva.

The left-side panel shows Sugreeva narrating his previous combat to Rama and Lakshmana – the combat is shown below. Vanaaras seated behind listen. How often do we see these in films, sometimes with voiceover? The right-side panel shows the subsequent Vali-Sugreeva combat, when Rama kills Vali with an arrow.

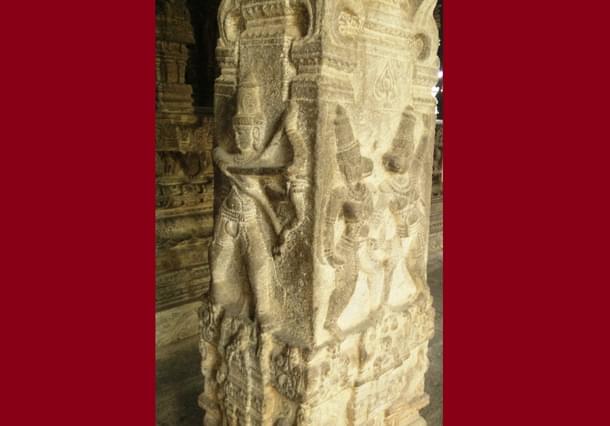

A Vijayanagara sculpture in a pillar of the Kanchi Varadaraja Perumal temple, uses a different technique for the latter scene. The vanara combat and Rama with his bow, are on two different faces of the pillar, to indicate that Vali and Sugreeva couldn’t see Rama when he aimed his arrow.

History and Evolution

India abounds in structural temples built in various periods of time, from the fifth century to the present times, and a number of other monuments like stupas and chaityas from even earlier.

Literature, coins, and even inscriptions in temples mention earlier temples, but they were often built of perishable material like wood and brick, and were rebuilt in later times, or suffered enormous destruction from invasions, and were never rebuilt. Some were buried either by natural calamities like floods, sandstorms, earthquakes etc or by abandonment and neglect for long periods.

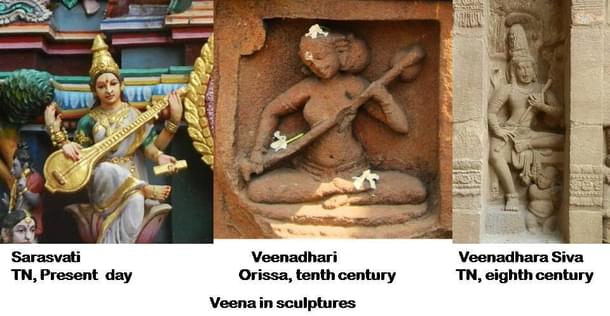

Temples of different eras and regions help us understand the development and evolution of art, aesthetics, and sometimes life and artifacts. Sculptures and paintings often preserve fashions, designs, objects, and cultural practices of a particular time, which have since been replaced or expanded. Take the veena, for example, which today has several strings and frets, and a large pot-like resonator. But this modern veena was invented by Maratha king Raghunatha Nayaka in Tanjavur, in the seventeenth century. Before that, the veena was a thin rod like instrument, as seen in these thousand year old sculptures, in Kanchipuram and Bhubaneshvar.

Similar differences in other musical instruments, jewelry, textile design, hairstyle, buildings, utensils, etc. are perceptible, if we pause and observe, rather than pass by glancing.

This essay was an introduction to sculptures. But they are best seen and understood in original context.

In future essays, we will discuss specific temples and their sculptures, along with architecture, inscriptions, and history to get a broader, deeper perspective.

R Gopu delivers lectures on astronomy, history, sculpture, Sanskrit, and Tamil, and is part of the Tamil Heritage Trust. He blogs here.