Culture

The Future Of Living Sanskrit

Subhash Kak

Feb 20, 2016, 01:38 PM | Updated 01:38 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

One needs to be able to look back in order to envision the future, which is why we need Sanskrit. It represents the cultures of both the south and the north. The scholar Bh. Krishnamurti, the author of the masterly The Dravidian Languages, liked to remind that the Ṛig-Veda, the earliest Sanskrit text, has features that are characteristics of Dravidian languages.

The great Tamil Chola dynasty and its successors used Sanskrit to carry Indian culture to Southeast Asia, and the earliest evidence of this interaction on the island of Bali in 200 BCE or thereabouts. Sanskrit is still used in the liturgy in Japan, Korea, Thailand and China.

Sanskrit is also of interest because its literature goes back further than any other living language, and this literature has profoundly influenced the cultures of vast regions of Asia. The major texts of the Hindus, the Buddhists, and the Jains are in this language, and it has an enormous number of texts on science, philosophy, arts, and music, not all of which have yet been studied by modern scholars. In a previous column I presented evidence on how Sanskrit texts appear also to have influenced the Christian gospels.

Linguists are interested in Sanskrit because of its connections with other members of the Indo-European family, for it can help untangle the relationships between its far-flung members, such as Irish and Bengali, or Norwegian and Sinhalese, and also explain obscure elements of European culture.

For example, the Latin word for sacred is sacer which carries not only the meaning of being consecrated to gods but also that of ineradicable pollution, or simultaneously veneration and horror. The word sacrifice, which properly means to make sacred (sacrificium), also means to put to death.

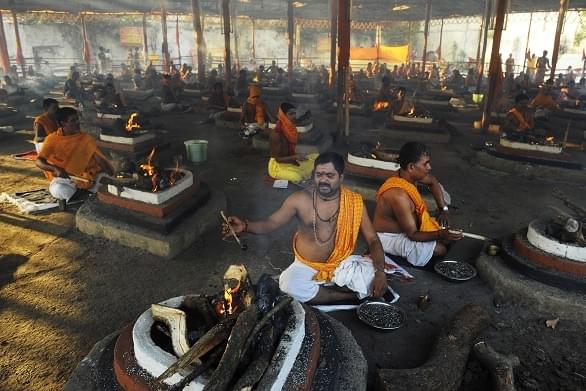

To understand this word, let us consider its cognate in Sanskrit yaj- which is worship or praise and from yaj also comes yajña or sacrifice. There is an esoteric reason why praise and sacrifice go together. The ritual is to help the sacrificer leave behind the previous phase of life (there is a symbolic killing of that phase, and also of an animal in the āsuric form of the ritual) and praise for the rebirth into a new one. The sacrifice was performed in India as fire ritual where fire or Agni symbolized time; similarly the Greeks had the fire ritual of Hestia and the Romans that of Vesta.

The tripartite conception of the Vedic society into priest, warrior, and cultivator is reflected in the triad Agni, Indra, and Viśve Devāḥ in India, or Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus in Rome. Religious and political sovereignty is viewed as a dual category of the jurist-priest (brāhmaṇa in India, flamen in Rome) and magician-king (rājā in India, rex in Rome) or queen (rājñī in India and regina in Rome).

Sanskrit helps understand the deepest layers of Iranian religion and culture as is well-known to scholars of Zoroastrianism (described at length in my book The Wishing Tree). The Avesta includes the Yasna (Sanskrit yajña) which later became the jashan or jashn of the later-day Persians. The chant of svāhā svāhā of the fire ritual is remembered as wah wah of the Persian celebration.

Sanskrit is the language of Yoga, which is hugely popular across the world, and its vocabulary embraces subtle aspects of spiritual experience. There is demand for Sanskrit by those who wish to read and understand original Yoga texts, and much of the tourism to India is driven by this demand.

Sanskrit is a living language, but barely so. Literature in Sanskrit continues to be produced but with negligible readership. This contemporary literature is primarily in the medieval forms of plays, poetry or mahākāvyas, which are far removed from the artistic sensibilities of our times.

Sanskrit is not doing well in India even though a lot of students do a course or two in it at school. The teaching is a rote memorization of the grammar which kills off interest even amongst those who might otherwise be motivated. No attempt is made to immerse the student in the language by using interesting stories as in the modern teaching of living languages across the world.

An Indian government committee recently made recommendations for reforms in the teaching of Sanskrit. While any reform is praiseworthy, a radical shift rather than incremental reform is the call of the hour.

Samskrita Bharati has worked hard to revive its conversational use. The idea is if the dead Hebrew language could be resurrected by the Jews after 1880, and now it is thriving in Israel, why can’t the same be done for Sanskrit which shares its vocabulary with nearly all Indian languages. But perhaps a better parallel is that of Latin for which also an effort is underway to make it a living language. In the United States, a growing classical education movement, consisting of private schools and home schools, is teaching Latin at the elementary school level and beyond. There are corresponding efforts in Europe and South America.

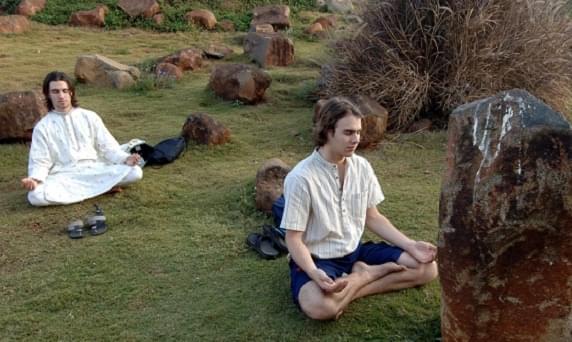

Let’s see how far the effort to revive Latin has gone. The Latin Wikipedia has 125,000 entries and it is in the 48th place, where thirteen languages have more than a million entries. Recent analysis of the Internet traffic reveals that India is 8th in the world in the use of Wikipedia in terms of page views per month, but Indian languages lag far behind the languages of other nations, and are even behind Latin. The situation couldn’t be more sad and embarrassing.

The table of Indian languages below shows that their ranks range from 57 for Hindi down to 133 for Sanskrit. Note that English has over five million pages whereas Hindi has just over 100,000.

Although over three million people have attended Samskrita Bharati camps, a switch entirely to its use requires a social and cultural ecosystem that is lacking in India. If a language only has old texts, then it is not a living language. Would people be interested in English, if all it had to offer was specialized medieval literature together with modern imitations?

A living language looks both at the past and the future. To infuse vitality, there should be a project to translate World classics into Sanskrit, even if only in abridged version. To begin with say 1,000 world texts should be identified and translated so that people can use Sanskrit as window not only into India but also into the rest of the world. These texts should include light literature, romances, poetry, plays, and other stuff, and they should be made available on the Internet.

This literature will promote the emergence of the ecosystem that Sanskrit needs to function as a living language.The thousands of Sanskrit teachers and students should also be required to contribute to Wikipedia and this should be done for other Indian languages as well. Let me conclude by a poem from the anthology Masterpieces of Religious Verse, ed. James Dalton Morrison (1948), which the editor claimed was based on a Sanskrit original:

The Salutation of the Dawn

Listen to the Exhortation of the Dawn!

Look to this Day!

For it is Life, the very Life of Life.

In its brief course lie all the

Verities and Realities of your Existence:

The Bliss of Growth,

The Glory of Action,

The Splendor of Beauty,

For Yesterday is but a Dream,

And To-morrow is only a Vision:

But To-day well-lived makes

Every Yesterday a Dream of Happiness,

And every To-morrow a Vision of Hope.

Look well therefore to this Day!

Such is the Salutation of the Dawn!

The attitude expressed in the poem needs to be embraced before Indian languages in general, and Sanskrit in particular, can claim their rightful place in world literatures.

Subhash Kak is Regents professor of electrical and computer engineering at Oklahoma State University and a vedic scholar.