Culture

The Languages Of Jambudwipa: A Tour Of The Rich And Colourful Tapestry Of Indic Languages

Sumedha Verma Ojha

Aug 26, 2016, 03:32 PM | Updated 03:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In this land of a thousand stories, all told in their own way, tracing the origins of each strand of this rich and colourful tapestry of languages is an almost impossible task; yet, it has to be attempted. Learning about these different languages is indispensable to understanding the Indic civilisation.

There are two distinct areas to be studied here, scripts and languages. Normally, languages come before the scripts. And this is more so the case for a civilisation based on the oral tradition, like the Indic one.

We start with the biggest mystery of them all, the language and the script of the Saraswati-Sindhu civilisation. It has not been deciphered definitively as yet, and theories abound. Since the examples from the script are mainly short inscriptions on small seals or, in one significant case in Lothal, on a sign for a factory or city entry, there is a point of view that it was not really a language and cannot be deciphered.

There are other points of view which suggest that it is related to Tamil, and yet others that it is related to Sanskrit, with merely a change of script from pictographic to phonetic. This view suggests that the phonetic script stuck, evolved into Brahmi and later, many others like including Devanagari and Grantha.

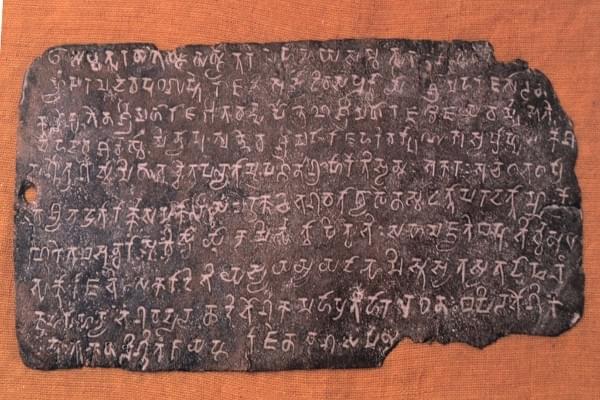

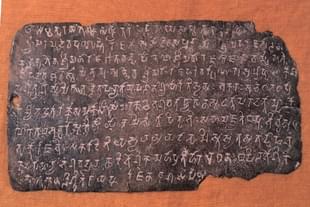

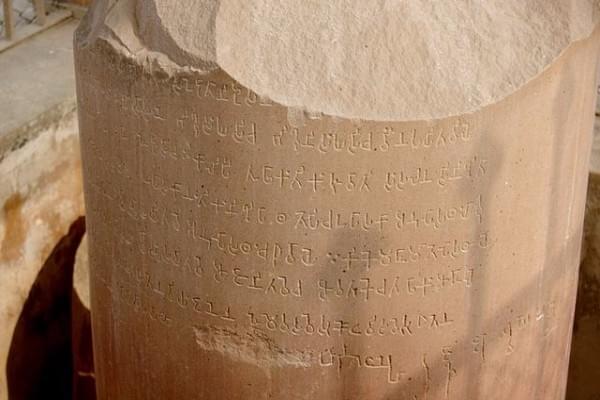

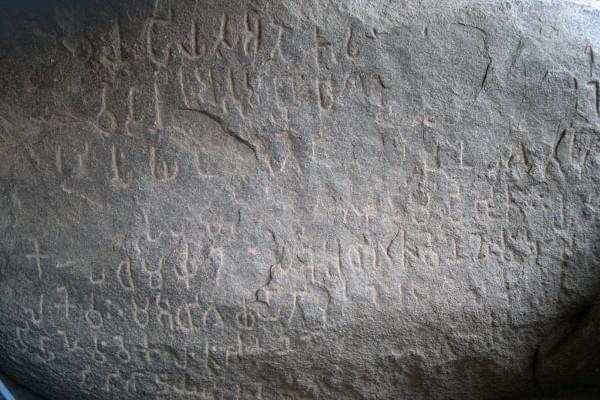

The Mauryan era provides an anchor for many seminal events of ancient India, and so it does for the evolution of writing. The inscriptions of Ashoka are among the first consolidated, extensive and organised pieces of writing found across the length and breadth of Jambudwipa and have naturally provided the basis on which to analyse ancient Indian writing and languages. These inscriptions are a treasure trove of information, as they were written not in a single script or language but many different ones depending on the region for which they were written.

Although early Indian historiography depended on these languages almost completely, they do not tell the entire story. The venerable and strong oral tradition of the subcontinent forms a strong counterpoint to the view that writing and languages only started being formalised during the Mauryan times. Sanskrit is obviously far older than Ashoka, and conflicting accounts left by Nearchus and Megasthenes about writing in India do not help in clearing the confusion. Tamil also has a fair claim to be a far older language than the time of the evolution of Tamil Brahmi.

An overview of the evolution of languages in the subcontinent and a little beyond will be useful here, after which we can discuss the scripts.

The Sanskrit oral tradition of the Vedic Age has to be kept in mind as the background for the study of the evolution of languages in India.

As far as Prakrit is concerned, by 800 BCE, India was divided into a number of kingdoms or mahajanapadas in the north and three or four of them in the south. The languages spoken could be divided into four groups, Udichya or Northern, Madhyadeshiya or Central, Prachya or Eastern and Dakshinatya or Southern, which was closely allied to Central Prakrit.

Geographically speaking, in the northern part of the country, these are three parts of the Sindhu and Ganga valleys which are still recognised as Punjab, Pachaha and Purab, or north, central and east.

The Kaushitaki Brahmana tells us that at this time, Northern Prakrit was seen as the best and most cultured while the eastern languages were seen as uncivilised. Perhaps changes were sweeping languages and dialects as the centre of power moved east to Pataliputra.

As far as Sanskrit is concerned, it was somewhere around this time, 600 BCE, that the great grammarian Panini composed his works. Spoken or Laukik Sanskrit had been differing from Vedic Sanskrit for quite some time, and he was the one who standardised this Laukik Sanskrit – or Bhasha, as he called it – by writing the great work of grammar, the Ashtadhyayi . This was different from what he called Chhandas, or the old language used in the Vedas.

Laukik Sanskrit or Bhasha was influenced by all the four Prakrits mentioned above, as also by Mundari and other tribal languages of the central and eastern parts of the subcontinent. The brahmanas and the shishtas who used Sanskrit as well as the different prakrits had a role to play in its formation.

We will come back to this point later , but let us go back to the evidence of Ashokan inscriptions to see if they bear out the above hypothesis about Prakrits.

The Brahmagiri group of minor rock edicts has thrown light on the administrative and linguistic organisation of the Mauryan Empire. A note has survived which tells us that the texts of the royal edicts were transmitted from the king to the viceroy at Suvamnagari, the southern capital of the Mauryans, from where they went to the town of Isila, close to Brahmagiri. It is clear therefore that the system was to send edicts from the Mauryan court to the viceroys and governors, who then had them distributed to officials under their administrative units.

In the context of this important conclusion, we can conduct a deeper analysis of Mauryan Prakrit edicts and understand how their dialectical variations later grew into the different languages of India.

Northern Prakrit, which gave rise to such languages as Hindi, Lahanda, western and eastern Punjabi and Sindhi, is represented in the Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra inscriptions. The Girnar inscription is a special case of this category, as it was also influenced by Eastern Prakrit.

A northwestern variation went to Chinese Turkmenistan and was the court language there for quite some time.

Eastern Prakrit has been found around Pataliputra, i.e., modern Bihar (Rummindei, Barabar, Lauriya), Western Uttar Pradesh (Kalsi), Eastern Uttar Pradesh (Sarnath, Kashi), Central Uttar Pradesh (Prayag) and Odisha (Dhauli and Jaugarh). The Kalsi dialect has a special significance as it has the closest connections with Hindi.

This Prakrit was the precursor to Purvi Prachya and Paschimi Prachya, which were nothing but Magadhi and Ardhamagadhi. Magadhi was much influenced by Central Prakrit and evolved into languages such as Bengali, Odia, Assamia, Bhojpuri, Magahi and Maithili. Similarly, Ardhamagadhi evolved into Awadhi, Bagheli, Chhattisgarhi and others.

This Eastern Prakrit language was the one in which the earliest Buddhist and Jain Agamas were composed before being translated into Pali, which is a closely related offshoot. The court language of the Nandas and the Mauryas, Pali was born in this court but did not become important till after the fall of the Mauryans.

Central Prakrit inscriptions have been found in places like Ujjain, Maski, Yerrugudi, Siddhpur, i.e., modern Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. The Girnar dialect can be considered part of this group too. The Deccan saw evolution into languages with old Kannada, old Telugu and Mundari basics. The languages of the Shaurseni region as well as Gujarat, Berar and Maharashtra, i.e., languages such as Marathi, Gujarati and Rajasthani, also evolved from here.

Tamil Brahmi Mauryan inscriptions have been found in central and southern India. They are in a special form of Brahmi evolved to represent the Tamil language. Predecessors of Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu existed in the south, along with other dialects like Kodagu, Gondi and Brahui of Baluchistan. There are obvious links between them, Sanskrit and the three Prakrits mentioned above, but they are not vikritis, or variations of Sanskrit or Prakrit.

Tamil is a special case with a hoary antiquity and a literary tradition which goes far back into the misty past with the legends of the three Sangams and Agastya, who was parallel to the Sanskrit grammarian, Panini, and composed the Agastyam or Akattiyam, the original Tamil grammar. Tradition says that Lord Shiva beat a drum with his two hands, the sounds from the left hand formed the Tamil language and those from the right formed the Sanskrit language. This goes to show the antiquity of the Tamil language, as well as, perhaps, a common meeting point of Tamil and Sanskrit.

A surviving fragment of the Akattiyam sets out the close ties that should exist between language and literature. The Sangam Age of Tamil literature is famous, and works said to be from the Sangam are extant although dated to around or after the Mauryan period. The most famous of these is the Tholkappiam.

Hero Stones in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, as also in western India, have interesting light to throw on the question of Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and their evolution. Their antiquity may be pre-Mauryan, and the Brahmi inscriptions found on them can provide insights into this complicated problem.

To pick up the story of Sanskrit again, further development of Central Prakrit is of great interest here since there is a close and deep relation between this dialect and Sanskrit as it evolved during the last centuries of the first millennium and later.

As mentioned before, the first language of the Buddhist Agamas was Eastern Prakrit; Ashoka references these in his edicts. Ashoka’s son, Mahindra, then took them to Sri Lanka. Now Mahindra probably received these in a transitional form of Pali influenced by Central Prakrit, as he and his mother belonged to Ujjain. There are also translations of Buddhist Agamas into a mixed Central and Eastern dialect of Mathura. Pali, therefore, had close links with both Eastern Prakrit and with the Ujjaini dialect.

Central Prakrit, in the first century CE, influenced the Sanskrit of the day with evidence from writers such as Ashvaghosha, fragments of whose works have been found in Central Asia. Shudraka’s Mricchakatikam is also in the same language and shows the same influences. It also influenced the Dardi language of the northern Himalayas.

It was understood by the speakers of the other three northern, eastern and southern Prakrits in some measure, as is evidenced by an analysis of Ashokan inscriptions, which showed people from different linguistic regions able to communicate in other languages of the kingdom.

Later offshoots of Central Prakrit became the Brajbhasha of 500 CE to 1700 CE , the Shauraseni of 600 CE to 1200 CE and modern Khadiboli and Hindi.

In Mauryan India, the linguistic spread in the north included Greek, which the Indians had acquired via the Iranian Achaemenids in the sixth century BCE. It was with the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor that Indians were first familiar, therefore the name ‘yavan’ for Greeks in Sanskrit.

By the third century BCE, a group from Takshashila had established Khotan (now in China) where the languages were Irani and Tibeto-Burmese, but the language of the court was a variation of North Western Prakrit. The later rule of the Kushans in northern India and parts of China deepened these influences in the northeastern part of the subcontinent.

To summarise, Sanskrit existed alongside variations and subvariations of northern, central, and eastern Prakrit, as well as other southern languages, and was heavily influenced by Central Prakrit. This Madhyadeshiya bhasha was the centre point with links to Sanskrit as well as its reach in the other linguistic areas.

We may now move on to a consideration of the earliest scripts in Jambudwipa.

The earliest references to writing in India are in Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, where he mentions lipi, i.e., script and also scribes who practised the art of writing. Nearchus, Alexander’s admiral as well as the Pali canon, provides further references to writing. As earliest writing was probably on palm leaf or cloth, which are easily perishable, it is not entirely surprising that the first examples, which have survived, are those written on stone, the Mauryan inscriptions.

Mauryan inscriptions are written mainly in two scripts, Kharoshti and Brahmi. The origins of both of these scripts are disputed.

There are theories which state that Kharoshti evolved from Aramaic while others argue that there is no evidence of evolution and it was a completely Mauryan script. It is written from right to left and probably developed for writing down Sanskrit and the Prakrit dialects of the northwest, especially Gandhara (modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan). It has also been found in Central Asia, in Bactria and Sogdia, parts of the Kushan empire and the Silk Road. It may have existed in Khotan and Niya up till the seventh century CE, but generally died out in India by the third century CE.

Brahmi is the other script, the mother script of the subcontinent, which is the origin of hundreds of scripts found in South, Southeast and East Asia. The numerals associated with this script are the Hindu numerals in use across the contemporary world.

As noted above, it is theorised to have evolved from the pictographic script of Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Lothal. It is, alternatively, given a Semitic origin.

It was used to write the inscriptions of Ashoka, but to assign it as having suddenly developed out of nowhere will not be very reasonable. The hero stones with short inscriptions, found in western and southern parts of the subcontinent are parts of the puzzle which still have to be pieced together to complete satisfaction. Also, given that the title ‘piyadassi’, which occurs on many inscriptions and has been identified with Ashoka, was also used by Chandragupta Maurya, his grandfather, may mean an adjustment of the timelines.

Bilingual Greek and Aramaic inscriptions have also been found dating to Mauryan India but have had little lasting impact.

This rather exhausting overview of languages and scripts in India brings out the complexity and multiplicity of languages and scripts in the Indian subcontinent, and the co-existence of Sanskrit and Prakrit for centuries. They had a deep and visceral connection with each other. Sanskrit, in later centuries, was often used as a lingua franca when people speaking different Prakrits were not able to communicate with each other. This is referenced in the Naishada Charita of Sriharsha, written in the twelfth century CE.

The Pollockian attempt to characterise Sanskrit as the language of exploitation and domination by Brahmins is not borne out by evidence, as many Prakrit languages were used by different royal courts for their administrative work, including the Mauryans. Sanskrit works of great import and significance in the fields of literature, religion, theology, science and mathematics continued to be composed along with the use of Prakrit as the language of the rulers. We have evidence from plays and poetry that all classes of society spoke Sanskrit and Prakrit. Poetry and literature were not out of the ambit of the Prakrits either; witness the power and vitality of Hala’s Gathsaptasati of the first century CE, for instance.

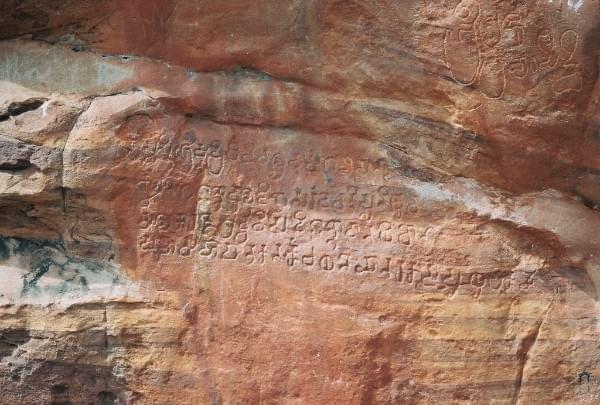

Let me conclude with an illustration from the Mauryan period. Writing and language are for the purpose of communication, and here is an instance of a very public expression of feelings. An artist, Devadina, could not restrain himself from expressing his love for the devadasi Sutanuka, writing in Magadhi Prakrit (in the Brahmi script). He wrote the following in the Jogimara Cave of Ramgarh Hills in Chhattisgarh:

“Sutanuka, the Devadasi! Sutanuka, the Devadasi! – I, Devadina, artist from Varanasi, love her.”

The first romantic graffiti of India!

Also Read:

Jambudwipa: The Seeds Of Political Unity In The Indian Subcontinent

Uttarapath And Dakshinapath: The Great Trade Routes Of Jambudwipa

After two decades in the Indian Revenue Service, Sumedha Verma Ojha now follows her passion, Ancient India; writing and speaking across the world on ancient Indian history, society, women, religion and the epics. Her Mauryan series is ‘Urnabhih’; a Valmiki Ramayan in English and a book on the ‘modern’ women of ancient India will be out soon.