Culture

The Tragedy Of Sanskrit: What Can Be Done To Democratise It Among People

Dr Nagendra Sethumadhavrao

Feb 08, 2019, 01:33 PM | Updated 01:33 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Since the past few decades, whenever the word Sanskrit comes up in popular media discourse, it can be fairly assumed that it would be for all the wrong reasons. Continuing with this trend, in the recent past the Supreme Court of India decided to refer the case against a Sanskrit prayer in Kendriya Vidyalayas to a larger bench, specifically to examine whether it violates Article 28 (1) of the Constitution (which mandates no religious instruction in state-funded schools ).

One of the biggest casualties in the polarised times of today is, sadly, the Sanskrit language.

On one end of the spectrum, we have torch-bearers who consider Sanskrit as a remedy to all modern-day problems. They end up making over ambitious and unsubstantiated claims like the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is using Sanskrit (there are many seekers asking questions about whether Sanskrit has been made compulsory in NASA in different web forums!).

Countering this claim, there has also been a Change.Org petition requesting NASA to clear their stance on Sanskrit. This claim has been peddled for a while now and the origins of this can be traced back to a 1985 paper on ‘Knowledge Representation in Sanskrit & AI’ by Rick Briggs who worked for the NASA. This is not to take away the genuine research on computational Sanskrit which we will discuss later.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have folks who would immediately prefix words like Brahmanical, tyrannical, casteist and divisive, the moment the topic of Sanskrit comes up in the mainstream discussion. Majority of these extreme statements and claims are made by folks who in all probability would have never done a serious or even a casual study of the language.

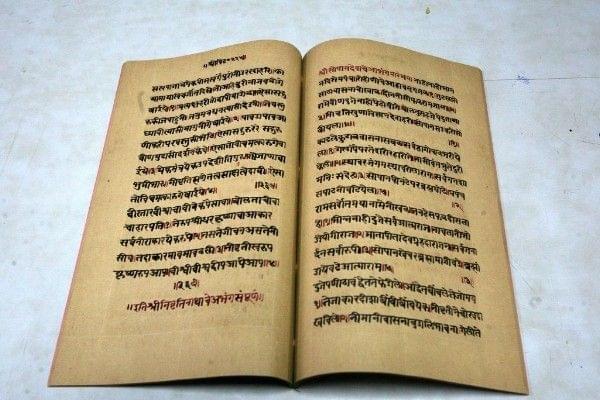

Sanskrit, undoubtedly, is one of the most structured and aesthetic classical languages of the world. But it is probably going through its own phase of ‘aranya rodhan’ (cry in the wilderness) especially in the land of its origin, and that is its tragedy. One of the most spectacular features of Sanskrit, is its usage of sutras or aphorisms in various knowledge representations.

The sutras have an inherent economical design where not even an extra consonant or vowel is added if it is not necessary. These self-sufficient economical sutras probably indicate a larger meta-thought that Sanskrit as a language is self-sufficient in its ingenuity and it does not need any extraneous hypothesis. Sanskrit needs attention as a language with no hyperboles so that it can be democratised among a large section of Indians who will automatically appreciate its beauty and richness.

The heavy focus on grammar and the marks-oriented way of teaching, results in children leaving school with three to four years of Sanskrit school learning, but without the ability to speak the language or appreciate its intricacies. Also, instead of debating whether “Sanskrit is the most computer-friendly language” or dismissing it completely as farcical, efforts need to be made to teach the very important generative features of the Sanskrit language.

As a country producing a large number of computer graduates, combining the growth of natural language processing automation with the computational linguistics of Sanskrit would be a great way to contemporise the essence of this language. Although it must be pointed out that there are institutions like Jawaharlal Nehru University investing in areas like computational Sanskrit, yet there is still a huge space to mainstream it for a larger section of students. The only silver lining through this, is the growing tribe of self-taught and passionate enquirers of Sanskrit who are discovering and researching despite the horrendous way in which Sanskrit was/is being taught in schools.

This also brings us to the question of whether Sanskrit should be made compulsory in schools. I believe that it should not be made compulsory. Rather its virtues should be sprinkled like spice and spread like aroma in a sublime way, and those who have a taste of it will naturally or voluntarily opt for it and further it.

As an example, while teaching mathematical patterns, chitra kavya (a form of poetry in Sanskrit which is constructed on different patterns) can be used as an example of making the subject visually appealing and enriching.

Finally, we come to the recent Kendriya Vidyalaya controversy. The court would have the final say on whether a Sanskrit prayer in Kendriya Vidyalayas violates Article 28 (1) of the Constitution.

But whenever such questions come up, it is good to run a test on the content. This test can probably be nomenclatured as the “Justice H R Khanna test of Secularism” on the content. In its order of 1994, the Supreme Court of India, while rejecting the charge that teaching Sanskrit as an elective was against secularism, quoted the great former Justice H R Khanna on secularism where he said, “Secularism is neither anti-God nor pro-God; it treats alike the devout, the agnostic and the atheist.. ”. In all probability the non-theistic Upanishadic prayer in contention “Asato Ma” when translated treats all denominations alike and passes the ‘H R Khanna test’.

Nagendra Sethumadhavrao is a Product Engineering Exec based in LA. He has a PhD in Innovation Management and works on Chaos Theory and Metaphysics. He can be reached at @dr_nagendra