Culture

This Artist Used Diyas To Give A Massive Depiction Of Ramdarbar, Coming Up Next Is The Biggest Depiction Of Shivaji’s Rajyabhishek

Sumati Mehrishi

Jan 22, 2020, 05:32 PM | Updated Jan 23, 2020, 12:28 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

When Mumbai-based artist Chetan Raut visualises Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's portrait, the image in his mind has minute units to it. These minute units go into making that one huge image, which is, by rule and principle, usually larger than life.

Hundreds and thousands of pieces of the chosen-by-Raut unit go into constructing that one image of the brave Maratha king.

Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was known for being an ardent bhakta of Ma Bhawani and Mahadev.

“Hara Hara Mahadev”

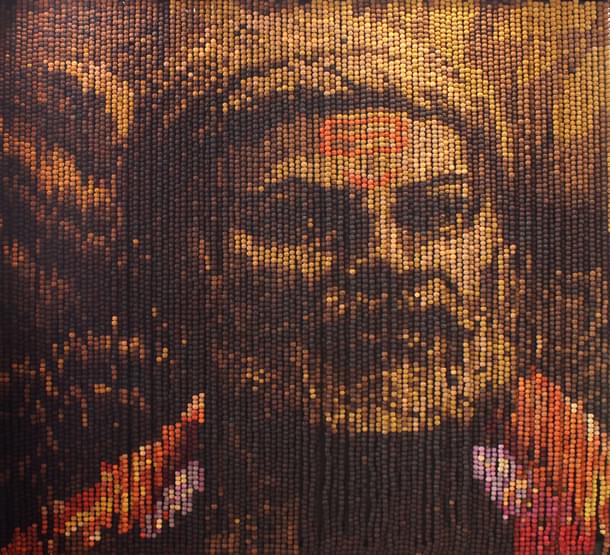

Raut has grown up to be an artist, hearing the chant and the cry of Shiva devouts. Rudraksha is used in the worship and the symbolising of Shiva, his shakti, and his japa. Raut chose rudraksha (the seed used as bead) as the material for building Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj's portrait in the form of a mosaic.

For this particular work, 14,000 pieces of panchamukhi (five-faced) rudraksha, painted as per the natural tone, were threaded together in garlands and arranged as per Raut's meticulous, software-backed, coding and colour placement.

Raut's next project and aim is to depict Chatrapati Shivaji's Rajyabhishek. He has chosen the unit for this one. It is the Rajmudra, the finger ring that symbolises the brave, devout warrior, and mighty flag bearer of the Maratha empire and saffron.

For sourcing the accurate replica of the Rajmudra in metal, Raut will be approaching makers in "all garhs (bastions) associated with Chatrapati Shivaji's rajya."

Raut wants this mosaic to be a lifetime installation and not a temporary display. “I want it to be used for connecting more and more people with Chatrapati Shivaji's life and meaning. A permanent mosaic means that a lot will go into its making and maintenance." He is working towards the funding of the projects.

Mosaic is Raut's instrument in the arts. After his training in the fine arts, image development and concept art, from the JJ School of Arts, Raut did not want to ‘chase’ paint, brush and canvas. “I grew up in the land of the adivasis in Maharashtra. I connect with the ground, I connect with nature, I wanted the ground to be my canvas.”

He wants Indians, especially the common man, to find and discover art through mosaic and wants to use the form to introduce the common Indian to visual arts in India.

According to him, India has an abundance of materials that can be used for mosaic making.

Currently, he is occupied with the themes of brave kings and warriors who have upheld the wellbeing of the praja as dharma. So, Chatrapati Shivaji is at the helm of Raut's purpose in art, and Rama, the king of Ayodhya, in its heart.

Raut's depiction of the Ramdarbar, the iconic image of Rama with Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman, has become a pilgrimage of sorts for visitors. It is displayed in Mumbai.

This mosaic, the latest from Raut, has won him a world record — His tenth. For this work, which depicts Rama with his bhakta Hanuman, and Sita and Lakshmana, his beloved companions to the vanvas, he used two lakh diyas.

These diyas were arranged as per Raut's picture and plan by a team of 30 helping members. The arranging of the diyas went on for three days.

Raut himself is miles away from Ayodhya. He wants to be in Ayodhya during Ramnavami, when he can actually lay on its soil his tribute to Rama and Ramarajya. “I want to take mosaic awareness to Ayodhya. For me, Ramdarbar is the perfect symbol representing the kutumbh values, which are the core of Indian culture and tradition.”

Raut's depiction of the Ramdarbar is 90 ft x 60 ft, and spread over 5,400 sq ft. Behind the world records for his mighty works is a meaning. Raut wanted to mark a new beginning with his tribute to Rama and Ayodhya.

Raut's exposure to mosaic heritage in the churches of France and Italy made him realise that Indian artists are capable of exceeding the artists in the West in retelling stories and expressing contemporary issues through mosaic.

He adds, “Artists in India can do much better than artists there by using mosaic. I keep encouraging my students towards it and want more and more people to be aware of mosaic as a form and want them to use it.”

Raut's version of the Ramdarbar has clicked with users on social media. Many viewers on social media are not inclined to contemporary art and the use of mosaic in concept art — on the lines of how the art market understands it and responds to it.

Hence, the growing popularity for Raut's work is a clear win for the material he chooses.

Raut's interaction with his material provides a much needed break from the tradition of using mosaics for Christian iconography and local interpretations. Mosaic is also used in urban public spaces. Their engagement with the onlookers is limited and restricted owing to the placement and site of arrangement.

Raut's mosaics are not pieces that can be packed in bubble wrap and taken home or for an office space.

“As soon as I share the work with the public, it ceases to be mine. This is exactly the idea behind my work. Art should reach the common man,” he adds.

Mosaic as a form is used in contemporary visual art, which reaches the prestigious galleries and art fairs. Coming to Raut's work, there is not even the scope of putting a red dot to it (the red dot is used by galleries and gallery owners at art fairs to denote that the work is sold). Raut's work is too mighty to be ‘owned’ and bubble wrapped in ‘ownership.’

It is, in this author's view, public art that the common man would immediately connect with and understand. This also means that it is available and ready to evolve in form, themes and subjects chosen in the future.

His work is a massive statement in concept, colour and unit. It has the advantage of detachment to one space. It has the advantage of mobility (just as sand artist Sudarsan Pattnaik's work).

It has the privilege — that of a flowing journey, where anything can be changed, anytime, depending on Raut's plan or what he calls ‘coding’. The material can be packed, carried, and rearranged.

Size of the depiction matters, especially in visual art where the work of installation is conceived and presented to say two stories in one. One, of the material or unit used, and two, of the depiction.

Raut tells this author that he is conscious of the size perception that the audience sees a work with. “Viewers register either the smallest or the biggest in size. I like to give the viewers the option of watching the work closely. Down to each unit. Once I offered them a tour on a crane for one of my mosaics. They were thrilled. I cannot forget their expressions when they noted the unit and connected with its role in the larger image.”

Raut's coding and playing with colours create illusions for the viewer. “I place red and yellow next to each other. It immediately becomes orange. You must see the expression of the viewer when he observes these colour illusions!” he adds.

Sometimes, viewers seem to check if there is a drawing on the ground that's supporting the mosaic work. “This is because people practise rangoli making at households and temples,” he chuckles.

He adds that it is after observing the work for longer that the viewers understand that there is no drawing on the ground and it is imagination backed by technology, which is laid out in the form of the mosaic.

The use of the minute to create the ‘huge’, has been previously attempted by any artists in the past, some to create objects, objects out of objects, works of installation, and sometimes murals.

Artist Subodh Gupta, who is known the world over for using home utensils to ignite the passion for memory and the idea of home and his own mother's kitchen in Bihar, has played with various sizes of the unit in steel, brass and even dung.

He has even beaten the units to accommodate them for his telling of the story in a frame — the frame you would associate with a work in paint on canvas.

Diyas have been used by artist Manav Gupta to create meaningful engagement with the kiln burnt clay as an element in environment - centered works.

So, what makes Chetan Raut stand out?

Chetan stands out (easily) among his peers for creating mosaics out of objects that change with subject/theme/message. He understands the Indic, he understands Indian strengths of retelling and simplifying the story and art.

He is doing less for himself and more for public art.

He taps on people's devotion and love for the image, person, episode or person depicted in the work. He is proud of the portraits he chooses. He walks towards contemporary themes easily. Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, Bal Thackeray, and Narendra Modi — are some of the portraits he has based on icons from today's times.

Fascinating is his mosaic dedication to Dr Kalam. The unit for this portrait in the mosaic: keys of the desktop computer. Black and white.

Raut's father worked as a cop and wanted him to be an engineer. He got upset when Raut chose to study art. His mother was supportive throughout. Seeing his success in what he has chosen to do, his father often turns up as a viewer.

Raut's depiction of the Ramdarbar reflects picture construction boiled down from the constant observation of home grown prints of the Ramdarbar.

Interestingly, Raut wanted to come up with this one on deepavali, last year. Mumbai rains were not kind however.

Ramdarbar is a visual memory of the completeness and the wholeness of Rama's arrival and a completion of one part of his journey, for many of us devouts.

It is witnessed in still as well as in the frozen movement of the performing arts. The scene is often depicted in books, calendars and printed versions of the Ramayana. The Ramdarbar scene culminates the Ramlila. For Raut, it symbolises Ramrajya.

He says, "Rama thought of the praja more than his own family. Rajya aaye to Ram rajya jaise aaye. The Ramdarbar highlights our kutumbh sanskriti.”

For the mosaic depicting Ramdarbar, Raut sourced the diyas — kiln-baked and painted in Delhi.

His exposure to Worli art during his growing years in Maharashtra helped him understand the skill of simplifying of the art of telling and retelling through mosaic. He moved over to another subject and concept — that of ‘fossil’ via print making. From there, to mosaic.

He says, “Characters, animals and other forms are presented in a simplified form in Worli art. My entire base for simplifying art for the common man has come from my observing the Worli style. The Worli artists’ devotion for nature is extraordinary. Jhaad ke ek ek patta, ek ek shape dikhta hai. Detail is important.”

This simplifying of art and motifs, according to Raut, is powerful and a strength very Indian. He wants to take this message and the glimpse of the Ramdarbar to Ayodhya.

That could be his closest view of himself as a small unit of the sprawling mosaic of what he understands as ‘Ramrajya’.

Sumati Mehrishi is Senior Editor, Swarajya. She tweets at @sumati_mehrishi