Culture

What Is Holi Without A Tribute To Colours Of India

Aneesh Gokhale and Anandi Paliwal

Mar 13, 2017, 01:42 AM | Updated 01:42 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Dyes and Pigments Of Ancient Assam

By Aneesh Gokhale

India is a land blessed with an abundance of colour. The colours reflect in our traditional dresses, ancient manuscripts and temple frescoes. Colours have been politically and economically important, as history involving indigo and Champaner tells us. Like many other regions of India, the North East is blessed with trees, flowers and the tradition of using natural dyes and pigments. The techniques in the use of these natural colours have stood the test of time. Let us take a detailed look at how Assamese life, clothing, headgear and manuscripts used a vibrant palette derived from nature.

A variety of plants such as the kuhum (safflower), palash (flame of forest), indigo and Indian madder were used to produce specific colours. There are 175 dye yielding plants found in Assamese literature. Flowers, leaves, bark extracts, plant based products, lac, shells, lamp black, gold, and insects were used for making the dyes. Lac colours are more popular in eastern Assam.

In Miniatures and Writing

Ancient and medieval Assamese used yellow, blue, red and black. These were obtained from Indigo, yellow arsenic, vermillion (Hengul) and kajal or pitch. Gold paint can be seen mainly in miniatures painted by Buddhists in Assam. The oldest painting has been dated to 1473 AD. The art of gold painting was called sonar – pani – chorowa. The people involved in extracting the gold and making it into a powdered form for use were known as “Sonowal”. For use on a miniature, the region to be painted was coated first with vegetable gum from the yang paw or Bhotera plant. Over this, the gold dust was uniformly sprinkled till it formed a layer. Coming to the Tai Ahoms, the miniatures were painted in layers.

Gold paint had another use at the royal Ahom court. At the coronation of a new king, the Mujumdar would write the name of the new ruler in gold on a piece of cloth. Another kind of ink or paint was known as “Mohi” and manuscripts written with it have survived centuries, even retaining their original lustre. The ink was prepapred by mixing various herbs, fruit pulp and even bark of some trees. The whole concoction after being mixed with cow urine was left to settle in a earthen pot with small holes beneath. It was usually done in winter. Drops of Mohi would start percolating after about 10 days. The ink used lasted centuries.

In Colouring Clothes

The most popular colours used in clothing and for colouring silk and cotton were red, light red, blue, yellow and green. Of these, yellow was used for turbans of royalty and senior officers. The colour was obtained from the kuhum or safflower plant. Bodos, Karbis and Mishis continue to use traditional dyeing methods.

Indigo was used by the Shyam tribe of Assam. Shyam directly lend their name to the state itself – Assam. The indigo being referred to, obtained from the Rom plant, was also called Rom. The indigo dye was prepared and stored in large wooden vats and buried in mud to preserve the temperature. Among the Shyam people, dyeing is usually done by the women.

How were yellow, blue, black and red obtained for using as colour for fabrics? The source materials for paint or dye to be used for miniatures was drastically different from that used to make coloured threads. Seeds of the Jarath plant were used to create red dye by boiling their shells. Threads dipped into the red dye would retain the red. Various plant-based substances were then used as mordant to make the dye adhere fast to the thread.

As for yellow, the use of safflower has already been mentioned. Another fern – the pulakait was also used to produce yellow dye. The roots of the plant were used to provide a rich yellow dye. Banana ash was mixed with the indigo dye to obtain a long lasting black colour.

Blessed with a huge variety of flora and being densely forested, the North East has developed a plethora of dye, inks and colours. From region to region within the North East, the plants and materials used for the dyes change. The Khasis in Meghalaya have a different bunch of plants supplying them their dyes. The tribes of Arunachal Pradesh do not use the same plants for making colours. The diversity of the dye-producing plants reflects the diversity of the region itself.

The Evolving Contemporary Palette

By Anandi Paliwal

Basant has passed on its bloom to Phagun. Radha and Krishna are engrossed in their eternal hide and seek under the full moon. In the morning, Barsana in Uttar Pradesh wakes up to music, traditional songs and colours. Marigold petals rush into little clouds of red, yellow, green and pink, of gulaal and abeer. Fragrance and petals, crisp and heady, mingle with heaps of colour thrown into the celebration of Holi.

White: Source: Shvet Abeer

Dilli

On Holi, the shvet abeer feels like the texture of moonlight. For Himanshu Verma, a well-known Delhi-based cultural impresario known for his love for the genda pool, white is the beginning and the culmination of a vibrant palette. “White cleans the other colours,” he says. The white in shvet abeer — pure and calming. Himanshu is not the only one delighted to play with white. Ko and Hukku, two Japanese kids in Barsana who are preparing to get drenched in colour, have fun with shvet abeer. Ko and Hukku pull out scoops of the dry colour, digging earthen saucers into heaps of the abeer. They are among the many Holi enthusiasts who make ‘swarang’ in Barsana for ‘Latthamar Holi’. Swarang is the name given to the pure and natural colours made at Red Earth, Himanshu’s initiative that celebrates festivals, textures, tastes, colours and gender.

The colours made of natural ingredients, mentions Himanshu in a Facebook post, “caused a stir amidst the chemical gulaals that everyone else was using.” He says, “I wish the natural and pure comes back forever.” At his studio terrace in Delhi, Himanshu supervises the process of making natural gulaal. Chandan Haldi, Godhuli Bela, Shvet Abeer, Chandni Chowk, Chanderi Gulab, Gulab Gulaal, Neem, Mehendi, Chandan, Haldi, and Lal Abeer are some of the other colours made at Red Earth. With an arrowroot base (like in synthetic holi colours), these colours are made by using natural colourants, grains and fragrances. Himanshu visits Barsana and Vrindavan on Holi for rang sewa, for songs of rasiya and phaag; for bhaang and thandai. This year, he sees a new expression of his rang seva in Ko and Hukku’s play with the shvet abeer.

Orange - Source: Haarsingar and Tesu

Uttar Pradesh

Haarsringaar, also known as Parijaat, or night jasmine, brings with it enormous fragrance, and a trail of orange in its tiny stem. At Navneet Raman’s Kriti Gallery in Varanasi, the meeting ground for artists and art connoisseurs from around the world, Haarsringaar releases its colour and fragrance in sweet and small measures. In this space, dialogue on contemporary art blends into the celebration of Benaras and India which extends from colours on the canvas to flowers. Haarsringaar, the flower offered to gods, is used to prepare a pale. Its stem, when dried and added to food or water, releases orange. Navneet uses Haarsringaar as a natural colourant in food and Tesu for the sweet mischief on Holi. The flowers are soaked overnight in water and can be boiled to obtain yellowish – orange colored water. The dried flowers can be powdered for a dry orange. According to Navneet, the flower finds mention in the folk songs of Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand. In West Bengal, it is associated with spring.

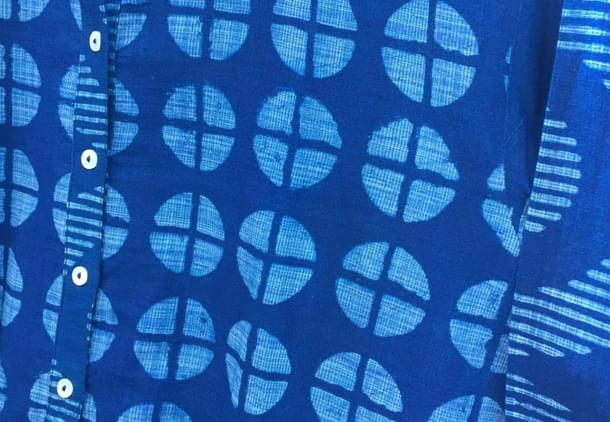

Indigo - Source: Indigo

Delhi

Amrich, the clothing label associates blue with a Japanese word for indigo – AI, also a term used for Love. For co-founders and designer duo Amit and Richard, it spells perfectly…. love indigo. Culturally, India was one of the biggest producers of natural indigo, but today, natural Indigo needs to be explored more in textiles. The label has done capsule collections using natural indigo in clamp dyeing, resist dyeing and block printing. The fabric is dipped in reduced indigo solution, squeezed and exposed to air. This procedure of dipping into reduced indigo solution, squeezing and exposing to the air is repeated several times (6-10 times) to get deep blue shade. An increased number of dips will get a deeper blue on the fabric.

Green - Source: Patang and pomegranate peels

Rajasthan

Alka Sharma, the owner of Aavran, a contemporary clothing brand from Udaipur, has switched to Patang (common name for several trees of family Leguminous-pulse family) for colouring fabric. Patang’s dye has largely been replaced by synthetic ones and is used in high-quality red ink. It is known as Japan wood, Sappan wood or Brazil wood, Baka, Chappanga, Sappange and Patumukam and is found in dry deciduous forests in India. It is also cultivated in Aravalli ranges, mostly in Alwar, Bharatpur and Dholpur districts of Rajasthan. Recently, Aavran has added to their palette the colour derived from nashphal — pomegranate peels. The peels soaked in water and left in the sun give a pretty shade of green. According to Alka, the antimicrobial properties of these peels stay on the dyed fabric upto ten wash cycles.

Yellow - Source: Turmeric

Meghalaya

In Meghalaya, indigenous handloom textiles are intrinsically associated with social and cultural life. According to Praveen Chauhan, founder of ART, Association for Reforming Traditions, turmeric is the brightest of naturally occurring yellow dyes and is one of the oldest natural colorants. The rhizomes of the perennial turmeric are a rich source of colour. A variety of shades-bright yellow, golden glow, ivory, sunset yellow, buff, light khakhi, golden yellow, cream, smoke brown, pineapple, olive green, and lemon can be obtained by using safe mordants in eco-friendly textile dying. Lakadong Turmeric grown in Jaintia Hills is said to be one of best.

Red - Source: clay

Gujarat

Pradeep Zaveri, an authority on the extinct Kamanghani art of Kutch, Gujarat, celebrates red prepared from indigenous clay cells — humarchi, available with local grocers. Clay cells rubbed constantly against stone slabs bleed a powder. The intensity of the red depends on the fineness of the pulverized clay. The yellow stone available in kutch, known as Kayo, turns into red powder when heated up. This is mixed with Geru for lipan kaam. The black colour was prepared from black coconut crust or the soot of cooking fires and lamps. Linseed oil was used as a medium to bind colours. Green colour was obtained from green stone. It was also made from mixing blue and yellow colours. Copper sulphate, algae and indigo (neel) were added to get blue. Yellow was prepared with yellow clay, haldi (turmeric) and cow urine. Some lime was added for a darker shade. Yellow was also obtained from a yellow pomegranate rind. The important shades used here are of green and yellow, dark brown, red and black.

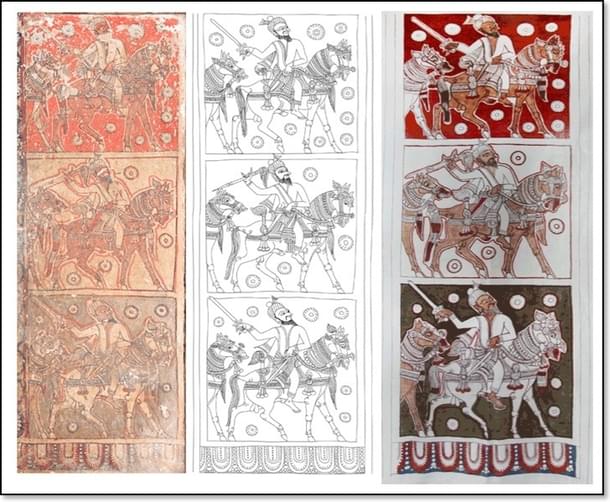

Black - Source: Fermented palm jaggery

Tamil Nadu

Art conservationist M V Bhaskar preserves mural paintings by digitising them and getting Kalamkari artists to replicate them. According to Bhaskar, Kalamkari is a hybrid process of resist dyeing and direct application of colours. In kalamkari, the outline is done in black and directly applied with a pen. Other colours are infused through a process of application, washing and boiling the cloth in buffalo or goat milk. Boiling (in goat’s milk) is the key to the right effect, consistency and blends. Only after boiling, alum and manjishtha combine to produce red. Each application of colour requires washing, boiling, or both, for the colour to come alive, show up and fix to the cloth. Black and Indigo are applied directly. Black is extracted from fermented palm jaggery.

The common mordants used are alum, which is inorganic, and myrobalan (Tamil: kaṭukkāi) which is organic. Plant sources commonly used are pomegranate peel with kaṭukkāi for yellow. Manjishtha (madder or alizarin) with alum yields the reds. Manjishtha gives pink. Other shades are derived from a mixture of red, yellow and indigo in varying intensities. Bhaskar believes that mural paintings and cloth paintings reinforce each other. A cloth painting tranforms the art fixed to a wall into a mobile exhibit. It outlasts the most durable photographic medium, meriting serious consideration as an archival medium. Colour derived from nature keeps this process and conservation alive.