Culture

With Bhandarkar’s Next, Is The ‘Reel’ Silence On Indira And Emergency About To Be Broken?

Gautam Chintamani

Dec 30, 2016, 07:31 PM | Updated 07:31 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

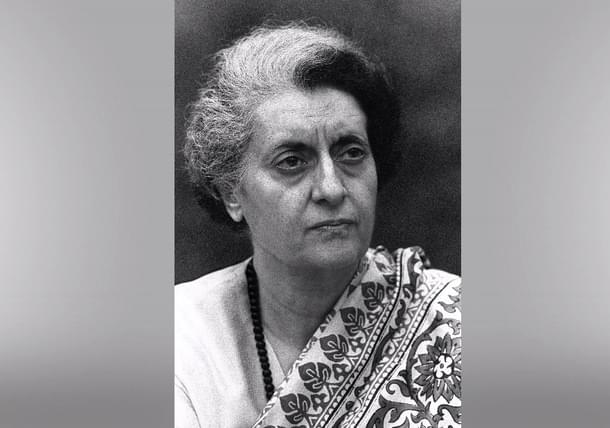

The Emergency declared across India by the then prime minster Indira Gandhi, between June 1975 and March 1977, remains one of the most talked about political events in contemporary India. Perhaps the darkest period in the history of the newly-independent nation, the Emergency was also a time when the civil liberties of over 600 million Indian citizens were suspended, almost all of Gandhi's political opponents were imprisoned and the press was heavily censored. Additionally, her son and political heir, the late Sanjay Gandhi, spearheaded a forced mass-sterilisation campaign.

One would imagine that such a phenomenon would inspire reams of literature and scores of films dissecting the sheer political audacity or the trials of the faceless Indians, who for no fault of theirs, ended up paying a heavy price. Yet, the Emergency continues to remain a barely explored topic across popular culture. Even after 40 years, there are only a handful of books or films that talk about the topic. While there has been an increase in the discourse on the subject, especially in the last five or so years, it still remains a largely uncharted territory considering the impact that it had on people.

That the political clout of the Gandhis (read Indira and Sanjay) would have scared filmmakers from talking about the 21-month long period is a no-brainer, but the manner in which some of the biggest filmmakers dealt with the Emergency, more than makes it obvious why the topic was not given importance in popular cinema across India. This becomes clearer from a cursory look at the either temporal ends of the Emergency. On the one hand the negative of Amrit Nahata's film Kissa Kursi Ka (1977) a spoof on the Emergency, where Shabana Azmi plays 'Janata' (the public) a mute, dumb protagonist, was not only banned, but reportedly had all its prints burnt by Sanjay Gandhi himself at his Maruti factory in Gurgaon, and on the other, Gulzar's Aandhi (1975) was banned as it was supposedly based on Indira Gandhi.

Perhaps the late 1970s or even the early 1980s were too close to the event to talk about it from a broader perspective, and of course, Indira Gandhi was back in power. The latter explains a lot about the short film eulogising Sanjay Gandhi at the beginning of Feroz Khan's Qurbani (1980). Narrated by Khan in first-person, the film Qurbani is dedicated to the memory of the 'Prince' and Khan bows in reverence to the 'Mother’.

The political reemergence of Indira Gandhi might be why no one truly ventured to look at the Emergency for what it really was. There is no denying the plot lines of Satyajit Ray's Hirak Rajar Deshe (1980), or Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Kotwal Saab (1977) or Khoobsurat (1980) were in fact, allegories of the Emergency but there can be no mistaking that they chose not to cast a direct look. It is not that filmmakers have not addressed the Emergency as a subject in a more direct manner but these instances are rare and in between. In last four decades only a handful stand out - Shahji N Karun's Malayalam film Piravi (1988) that explored the life of Professor K Eachara Warrier whose son was believed to have been murdered during the Emergency; Balu Mahendra's Yathra (1985), which was a remake of his own Telugu film Nireekshana (1982), a fictionalised account of the human rights violation by the police and the prison authorities during the Emergency; and Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005) that narrated the era’s social and political changes through the intertwined lives of three youngsters.

In just a little over a decade, Mishra’s film has come to be seen as the ‘go-to’ film on Emergency and much of this makes sense considering that even some of the direct references to Emergency in Indian cinema were adaptations. Mahendra’s Yathra was an adapted from a Japanese film, The Yellow Handkerchief (1977) where three strangers embark on a road trip, which in turn was inspired by a column written by American journalist Pete Hamill for the New York Post in the early 1970s.

This might change with Madhur Bhandarkar’s upcoming film Indu Sarkar, which is said to be set during the turbulent times of the Emergency.

Known for making films that are often inspired by real life incidents, Bhandarkar’s cinema in its own inimitable way captures not just moments but also the zeitgeist of our collective consciousness as a nation. It would not be totally incorrect to say that had it not been for Bhandarkar’s Chandni Bar (2001), the grim reality of Mumbai’s dance bars would not have become common knowledge. Similarly, it was Bhandarkar’s Page 3 (2005) that single-handedly established the ‘Page 3’ culture where making it to the events page of the city supplement of one of India’s leading newspapers had come to become almost a matter of life and death. Be it Satta (2003) where he explored the underbelly of today’s politics or Traffic Signal (2007) where he surveyed the business of business surrounding a traffic signal in Mumbai, Bhandarkar’s depiction of urban Indian reality has become acceptable. Even though a sense of generalisation pervades Bhandarkar’s narrative, which, at times, also runs the risk of simplifying things to such an extent that the essence of the message is lost, Bhandarkar knows how the use the medium brilliantly.

Look longer at his films and you would see how he tends to tell the same story over and over again – you can find Mumtaz (Tabu), the bar dancer of Chandni Bar – the underdog who ends up bartering her soul in order to survive the big bad city called Mumbai and in turn losing everything but picking up pieces in the end and carrying on bravely – in most of his films with just a different setting. So, the dance bar in Chandni Bar becomes the boardroom in Corporate (2006), a film set in Heroine (2012), a party office in Satta the backstage in Fashion (2008), the footpath in Traffic Signal and a jail in Jail (2009).

Irrespective of the limitations of his films, Bhandarkar is probably the best choice to make a popular film on an issue like the Emergency. Earlier this year, in May, there were reports that Bhandarkar was going to call his film Main Indu and the lead, Kirti Kulhari (Pink), was said to have been playing a character modeled on Indira Gandhi. Much of it could be hearsay for the imagery on the film’s teaser poster suggests something else. The image of a raised handcuffed hand much like in the iconic image of George Fernandes’ arrest during the Emergency somewhere hints that this could be a tale of a woman who rises against the tyranny of those in power.

Regardless of what the actual story would be, Indu Sarkar could become a much-needed treatise on the era thanks to a combination of Bhandarkar’s standard story-telling style and the access he had had to people who endured much of what the Emergency had to offer first-hand. Bhandarkar is said to have had long meetings with not just politicians such as L K Advani and Subramanian Swamy, but also journalists Coomi Kapoor and Tavleen Singh. Both Kapoor and Singh have chronicled their own experiences in books and would have no doubt shared many personal anecdotes that would really set the mood. Kapoor’s The Emergency: A Personal History is replete with experiences that the then young journalist underwent, where she faced the full fury of the establishment, and Singh’s Durbar narrates her observations where as a 25-year-old junior reporter, she knew the ground reality, but as a close friend of the Prime Minister’s son (read Rajiv Gandhi), she also witnessed how the influential in Delhi remained unaffected by the state of the nation. Together, the two offer a vivid eyewitness account of both sides of the fence and in Bhandarkar’s hands, it might be interpreted in a manner where the average viewer would be able to understand the dark era and also be able to put things in a new perspective.

Many have debated the Emergency and yet it continues to remain a never-ending jigsaw puzzle even with all the pieces right in front of our eyes. Coming to terms with an event such as the Emergency then and coming to terms with it now are different things. It’s baffling why even those who had a platform to talk and share the horrors of what the whole thing entailed decided to wait for decades before talking about it. Is it true then that finally there is an environment now where everyone from the common person to seasoned journalists such as a Coomi Kapoor or a Tavleen Singh and a filmmaker such as Bhandarkar, whose films rarely made a political statement, can express themselves?

Snooty critics and such might grumble about Bhandarkar being the filmmaker dealing with something such as the Emergency, which in their opinion might need something more than a folksy style. But it is hard to think of any other filmmaker who has explained complicated and often complex socio-political bookmarks in India’s recent past to so many people with such ease. Bhandarkar is the kind of filmmaker that you may never entirely love but at the same time, there is no denying that he is also a filmmaker who does not shy away from showing things the way they are.

Gautam Chintamani is the author of ‘Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna’ (2014) and ‘Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak- The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema’ (2016)