Defence

1965 War: When An Indian Fighter Pilot Landed On An Abandoned Airstrip In Pakistan

Prakhar Gupta

Sep 09, 2024, 01:40 PM | Updated Sep 13, 2024, 06:03 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In September 1965, a month after it failed to instigate Kashmiris into rebellion against the Indian state, the Pakistan Army decided to set in motion Operation Grand Slam.

It was aimed at capturing the vital Akhnoor bridge over the fast-flowing Chenab, a weak link along the most viable route connecting the Kashmir Valley with the rest of India.

The plan was to deny India supply lines to the state, thus taking over without resorting to an all-out war.

Bearing the brunt of the attack on the Indian side was 3rd Mahar and a squadron of AMX-13 tanks of the 20th Lancers, some of which had been airlifted to Chushul to halt the invading Chinese in 1962.

Outnumbered and outgunned, troops sought India Air Force’s (IAF’s) assistance on 1 September. And it arrived, although with some delay.

Pathankot, the nearest airbase, had two squadrons of Mysteres and one squadron of Vampire fighters, which had been moved here recently from Pune. The Vampire fighters were the most obsolete aircraft in the IAF's inventory.

The Pakistan Air Force (PAF), on the other hand, enjoyed qualitative advantage over the IAF, though it was outnumbered by a fair margin. The PAF had acquired at least 120 F-86 Sabre fighters from the United States in the late 1950s, 24 of which were equipped with the Sidewinder air-to-air missile, first in South Asia. It also had the latest Sidewinder equipped F-104 Starfighters.

Responding to the Indian Army’s SOS, the IAF scrambled 12 Vampires and 14 Mysteres from Pathankot to blunt the Pakistan Army’s offensive in Chhamb.

A pair of PAF Sabres, which was over the area to provide cover to the advancing Pakistani armour, managed to shoot down four obsolescent Vampires of the IAF that evening. Three pilots were killed while one managed to bail out at the right time.

The IAF’s first mission of the war had not ended well.

In one of his writings, Group Captain Mohan Murdeshwar, who participated in the war, recalls: “We landed at Pathankot, at sunset and while taxiing to the dispersal I was greeted by dejected and sad looking faces of course mates and others standing alongside the taxiway. It was only when we all walked out to the Technical Area, that we learnt of the four Vampires that had been shot down on their attempt to neutralise the Pakistan Army’s large scale thrust towards Akhnoor”.

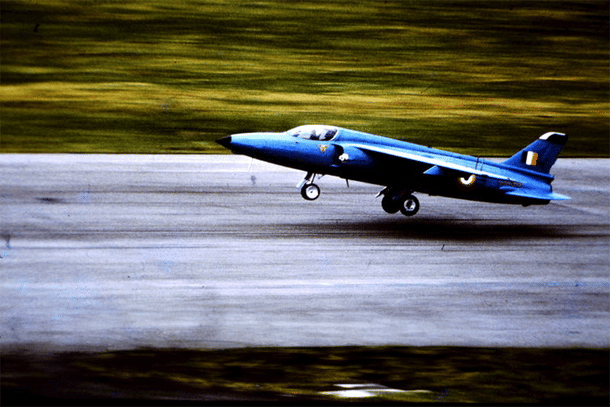

On 2 September, realising that its outdated Vampire fighters were no match to PAF’s Sabres, the IAF decided to throw into action its smaller and highly manoeuvrable Folland Gnats.

Four Gnat fighters of the IAF’s 23 Squadron, stationed in Halwara, were dispatched to Pathankot under the command of Squadron Leader Brijpal Singh Sikand.

Another detachment of four Gnats, stationed in Ambala, was also moved to Pathankot under the command of Squadron Leader Johnny William Greene, taking total the number of the fighter at the airbase to eight.

The Gnats were flown to Pathankot at low level to avoid radar detection. Consequently, Pakistan did not know that the fighters were moved.

“On the tarmac we were told that our task was to even out the score — to shoot down four enemy jets,” recalls S Krishnaswamy, one of the eight fighter pilots who went on to become the chief of IAF in 2001, in an Indian Express article.

Sikand, although the senior most of the eight, let Greene take over as the commander of the entire detachment as the latter was a more experienced flier.

The IAF’s plan, P V S Jagan Mohan and Samir Chopra write in the book India Pakistan Air War Of 1965, was to use a formation of the Mystere fighters (two squadrons of which were available in Pathankot) flying at medium altitude to lure out Pakistani Sabres while the Gnats fly low to avoid radar detection. When the Sabres were out to shoot down the Mystere, Gnats were to climb up and engage them.

On 3 September, “as we arrived at the Chamb sector, the Mysteres at height, were picked up by Pak radar and as foreseen the Sabres arrived to meet them. At 501 SU’s warning, the Mysteres, dropped height and both our Gnat formations moved up to engage the Sabres,” Group Captain Murdeshwar, who was flying a Gnat, writes.

Six Sabres and two Starfighters of the PAF were scrambled. In the dogfight that ensued, Squadron Leader Trevor Keelor, fired at a Sabre using the twin 30mm cannon on his Gnat.

Later that day, the All India Radio announced that he had become the first Indian pilot to shoot down a jet in air to air combat. (Apparently, the Sabre, which Keelor fired at, had managed to reach back to its base, although badly damaged.)

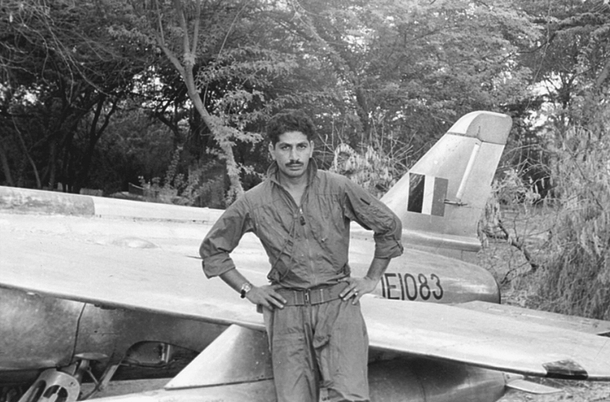

In the midst of the dogfight, Sikand, the second pilot of the finger four formation of four aircraft, went missing. “Siki, unable to maintain position, fell off, and disappeared from sight,” Group Captain Murdeshwar recalls.

Low on fuel towards the end of the dogfight, the fighters started returning to the base, only to discover that they had lost the senior most of them all. Initially, it was believed that Sikand was shot down by a PAF fighter. However, to much relief of the other seven, it soon emerged that Sikand had landed on an abandoned airstrip in Pakistan’s Pasrur.

It was found that Sikand’s aircraft was low on fuel, many of its systems had failed, he had lost his bearing. Having flown the Gnat for some distance in this state over unfamiliar territory, he spotted an airfield and landed there under the impression that it was in Indian territory. Before he could realise and recover from the shock, Sikand was taken as a prisoner of war (PoW).

“Most aircraft at that time did not have radars, or GPS systems or navigational aids. All the pilots had to use their maps and the aircraft compass to do their navigation back to base using visible landmarks,” Mohan and Chopra point out in their book.

Interestingly, Pasrur lies west of Pathankot, straight as the crow flies.

Pakistan, being as good at airing propaganda then as it is now, quickly claimed that one of their Starfighters had forced Sikand to land.

The captured aircraft, various Pakistani accounts suggest, was initially camouflaged and kept at Pasrur to prevent it from being bombed by the IAF.

Later, it was flown to Peshawar by Flight Lieutenant Saad Hatmi, who had some experience of flying Gnats during his stint in the United Kingdom. The fighter is said to have been extensively flight tested by the PAF to gauge its performance.

In his account of the war as one of the eight pilots, Air Chief Marshal Krishnaswamy, recalls Sikind, “with his trimmed hair and beard, saying he would be able to pass off as a Mussalman if he ever ejected in Pakistan”.

Air Marshal K C Cariappa, the son of Field Marshal K M Cariappa, who spent time with Sikand as a POW in Pakistan, recalls in his account, among other things, how the Gnat pilot chatted up a Hindu sweeper, who appeared sympathetic to them, to dig information about their repatriation to India.

Today, the captured Gnat fighter stands as a war trophy at the PAF’s Karachi museum. Sikand, who remained in Pakistani custody till January 1966, rose to become Air Marshal and retired from the IAF in October 1986, having earned an Ati Vishisht Seva Medal in 1978 and a Param Vishisht Seva Medal in 1987.

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.