Economy

Heterodox Economics And The RSS

Prof. Vidhu Shekhar

Aug 31, 2025, 08:00 AM | Updated 09:12 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

During my PhD days at IIM Calcutta, I discovered that there exists an entire stream of economics that predicted real-world outcomes far more accurately than the theories taught in universities worldwide. This field, known as Heterodox Economics, offers frameworks far more complete and better suited to explaining the real world than the dominant theories.

This curiosity stayed with me. Fascinated and perplexed at why it was neither taught nor adopted, I once posed a question to the head of a national institute of public finance at a conference organised by my alma mater. Was the government thinking about heterodox theories?

His answer was intriguing. He mentioned that in recent interactions with senior RSS functionaries, he found their economic ideas strikingly aligned with heterodox economics.

That comment stayed with me. Over time, I examined the matter further. RSS-linked campaigns, official statements, and the priorities articulated by leaders consistently revealed an economic philosophy rooted in mercantile practice, institutional trust, ecological stewardship, and civilisational ethos. These emphases converge strikingly with what economists across the world classify as heterodox economics.

But before examining it, we must first understand what heterodox economics really is.

The Hidden Architecture of Economic Thought

What is taught worldwide today, including in India, is the neoclassical framework, commonly referred to as mainstream economics. It represents just one theoretical approach, yet it is taught at nearly all levels of education across the globe.

This orthodox framework that dominates university economics departments worldwide has achieved something remarkable. It has convinced generations of students and policymakers that it represents the entirety of economic science. In effect, it has produced an intellectual capture on a global scale.

The physics analogy is revealing. Imagine, in physics, all universities teaching only Newton’s laws while ignoring relativity and quantum theory. In physics, students learn multiple theories and understand each has its place. Economics, by contrast, presents one model as the entire science.

Worse still, mainstream economics consistently fails to do its central job: anticipating what will actually happen.

Before the 2008 financial crisis, leading economists declared the world had entered permanent stability. Earlier, they insisted zero interest rates must always cause inflation. Yet Japan, and later western countries too, disproved this for decades. More recently, they failed to foresee COVID-driven supply chain inflation, then scrambled to explain it after the fact.

Mainstream economics today functions less as science and more as dogma, explaining events after they occur, yet still dictating government policy worldwide.

The Spectrum of Heterodox Economics

Economics as a science is far more than a single theory. Heterodox economics represents a family of approaches that illuminate what orthodox models ignore.

Just as relativity, quantum theory, and string theory offer different views of physical reality, heterodox economics provides multiple lenses for understanding economic life.

The major strands include Post-Keynesian economics, Institutional economics, Ecological economics, and Polanyian theory, among others. Of these, Post-Keynesian economics is especially developed, with a strong record of predicting financial crises and explaining the dynamics of modern economies.

Post-Keynesian Economics and the RSS: Credit as Money

Mainstream economics typically teaches that money originates with governments and central banks. Post-Keynesian economics demonstrates this is only part of the truth. Money also comes into being when banks extend loans. A business or household does not merely draw on recycled deposits. New credit is created, and that credit becomes money.

In this perspective, the money supply via credit expands or contracts with confidence and trust in the economy, not simply with government policy. Credit, therefore, is the real fuel of growth.

Indian mercantile traditions had recognised this centuries earlier. Merchants relied on hundis (letters of trust) that circulated as money within networks of trade. These instruments, backed by reputation, often moved across markets as readily as coin.

This understanding also underpins Hyman Minsky’s theory of financial instability, developed within Post-Keynesian thought. Minsky showed why periods of stability often breed risk-taking, bubbles, and collapse, a dynamic mainstream economics consistently overlooked. His insight, that stability is destabilising, has been vindicated repeatedly, from the 2008 crash to recent market volatility.

Echoing this insight, the RSS view, shaped by India’s mercantile classes, stresses credit as the foundation of economic vitality. Its organisations consistently promote credit access for small and medium enterprises, highlight trust-based instruments, and call for financial systems that strengthen local enterprise.

In this respect, Post-Keynesian theory and RSS practice converge: credit functions as money, and its circulation is the primary driver of growth.

Institutional Economics and the RSS: Markets Need Culture

Institutional economics argues that markets are shaped not only by prices but also by institutions, norms, and values. Contracts, trust, and culture determine how economies function. In simple terms, it means that culture and trust matter as much as, or even more than, supply and demand.

The RSS perspective reflects this tradition. It explicitly advocates that Indian markets must remain anchored in institutions, norms, and community values. In multiple public statements, RSS functionaries stress that economic decentralisation, cooperative networks, and guild-like associations are indispensable for Indian growth. This emphasis mirrors Institutional Economics’ focus on the role of norms and trust in shaping market outcomes.

Today, the RSS stresses the need for institutions anchored in Indian cultural values rather than borrowed wholesale from the West. Economic success requires institutions grounded in India’s civilisational foundations, a form of institutional wisdom that treats culture as the substrate of effective economic systems.

Institutional economics and RSS thinking agree: markets cannot exist in a vacuum; they are sustained by the quality of social institutions. Put simply, both believe you cannot separate markets from the culture they operate in.

Ecological Economics and the RSS: Sustainability as Dharma

Ecological economics begins with a fundamental recognition: the economy is embedded in nature and cannot expand without limit. Mainstream economics often assumes limitless growth, treating nature as merely a resource for utility.

Ecological economics argues that the economy runs on finite energy and resources. Sustainability and balance with nature must therefore be central to economic thought.

This systems thinking, central to ecological economics, finds natural expression in Indian thought, which sees man and nature as part of one ecosystem. This is well visible in the personification and deification of mountains, rivers, lands, and animals.

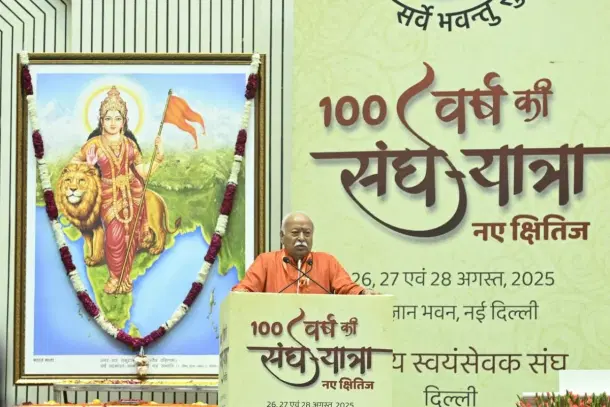

The RSS view resonates with this principle and is consistently reflected in its campaigns. From the Swadeshi Jagran Manch to the Swavalambi Bharat Abhiyan, ecological stewardship, sustainability, and balance with nature are recurring priorities. Mohan Bhagwat himself has stated that India’s economy must be built on local resources with ecological balance at its core. This orientation parallels ecological economics’ insistence that growth without balance is not progress.

Polanyian Economics and the RSS: Markets Embedded in Society

Karl Polanyi’s Great Transformation argued that markets are not natural or self-regulating. When separated from society, they erode community bonds, reduce people to commodities, and generate crises. Societies inevitably push back to protect human values from market excess, a self-protecting response he called the “double movement.”

The RSS worldview reflects this logic. It accepts markets as useful but insists they remain embedded within social and cultural goals. RSS-linked organisations emphasise redistribution through festivals, dignified labour such as shram-dan, and community-based welfare.

The Swadeshi Jagran Manch, for instance, has argued that trade and enterprise must serve collective well-being rather than abstract profit-seeking. Mohan Bhagwat has also stated that international trade should remain voluntary and rooted in self-reliance, not in unfettered market logic.

RSS thought parallels Polanyi’s warning against “fictitious commodities,” which is defined as the treatment of land, labour, and money as mere goods. In Indian tradition, land is revered as Bhumi Mata, labour carries dignity through communal practices, and money is embedded in trust-based networks.

Both perspectives converge on a clear principle: when markets dominate society, they undermine the very foundations of economic life.

What This Reveals

The alignment between RSS economic thought and heterodox economics reveals something vital about knowledge itself. Sophisticated economic insights can emerge from lived tradition as readily as from academic theory.

Indian mercantile communities understood credit creation through hundis centuries before Post-Keynesians formalised the idea. Guild systems reflected principles of institutional economics long before they were codified in textbooks. The view of nature as sacred anticipated ecological economics, and festivals of redistribution reflected Polanyian insights about embedding markets in society.

This is indigenous heterodoxy, civilisational wisdom reaching many of the same conclusions as heterodox economics. Far from being speculative, these parallels are documented in RSS-linked statements and campaigns, from SME credit priorities and cooperative institutions to ecological sustainability and community welfare.

The convergence between heterodox economics and RSS economic thought underscores a broader truth. Economic insight can emerge from both academic theory and lived tradition. Indian mercantile practices anticipated credit theories, guilds embodied institutional economics, and ecological reverence prefigured sustainability debates.

Recognising such wisdom challenges the monopoly of Western academia and points to universal principles that transcend cultures and epochs. The future of economics may depend less on abstract models and more on traditions that sustain real communities and environments.

At the very least, it shows that economic insight has many valid sources, and true intellectual humility requires recognising wisdom whether it emerges in university seminars, centuries-old markets, or movements like the RSS.

Dr. Vidhu Shekhar holds a Ph.D. in Economics from IIM Calcutta, an MBA from IIM Calcutta, and a B.Tech from IIT Kharagpur. He is currently an Assistant Professor in Finance & Economics at Bhavan's SPJIMR, Mumbai. Previously, he has worked as an investment banker and hedge fund analyst. Views expressed are personal.