Economy

India’s Missed Stitch: What Shahi Exports Got Right In A Broken System

Amit Mishra

Apr 23, 2025, 01:55 PM | Updated Jul 01, 2025, 09:21 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In Faridabad, the whir of sewing machines never stops. Hundreds of women work in synchrony—bending, stitching, cutting, pressing. For Saroj, now a supervisor managing 18 operators, this sound is the rhythm of transformation. Her own.

Eighteen years ago, Saroj stood at the gates of Shahi Exports’ factory for the first time, nervous and unsure. Married young, mother to four children, and with a family that survived on small-scale farming, the very idea of a job seemed foreign. But tragedy struck—two deaths in the family—and she found herself seeking stability and purpose.

Her neighbour told her about a garments unit hiring women. With trembling hope, she crossed districts and boundaries—literal and cultural—to apply. The factory overwhelmed her at first, yet it was the sight of women confidently maneuvering their stations that lit a spark: “If they can do it, so can I,” she thought.

Today, her family lives in Faridabad, her children educated, and her husband works beside her. Stories like Saroj’s are not rare at Shahi—they’re the norm.

At the heart of India’s textile export sector, Shahi has emerged not just as a manufacturer, but as a social engine, carving out a unique space that no one else has managed to claim.

Though well-known in industry circles, particularly in the international apparel circuit, Shahi remains relatively unknown to the average Indian.

A Seamstress, A Stitch, A Start

The story of Shahi doesn’t begin in a glitzy boardroom—it begins in a modest Delhi home. Sarla Ahuja, a young woman armed with little more than a sewing machine and a dream, stitched the first seams of what would become a remarkable journey.

A Class 10 graduate, she had left her factory job to raise her two sons, but the itch to work persisted. From her living room, she began fulfilling small export orders to the US—and gradually brought other women from nearby slums into the fold.

For these women—accustomed to housework and invisible labour—Sarla offered something radical: a wage, a skill, a community. She taught them hemming, stitching, finishing. Slowly, the network grew.

In 1974, with just ₹5,000, Sarla set up Shahi’s first production unit with 15 women in Delhi’s Ranjit Nagar—unknowingly laying the groundwork for what would become India’s largest apparel exporter.

As the venture grew, her sons Harish and Sunil came on board. Harish focused on Indian expansion; Sunil explored the customer base in the US. The company became a rare bridge—linking women in Indian homes with store shelves in Europe and America.

Karnataka And The Power of Scale

By 1988, Shahi was ready to stretch beyond the narrow bylanes of Delhi. Its next chapter unfolded in Karnataka—a state already humming with apparel activity, thanks to established players like Gokaldas Exports in Bangalore (now Bengaluru).

Karnataka offered everything a growing manufacturer could hope for: solid infrastructure, port access, and, importantly, an educated and trainable workforce. Bengaluru, with its openness to women in the workforce and relatively low union friction, became the springboard for Shahi’s southern leap.

But Shahi didn’t just expand—it scaled smartly. Instead of concentrating operations in one city, it strategically scattered its factories across multiple districts. This decentralized approach allowed more locals—especially women—to take up jobs closer to home.

Two major policy shifts supercharged this momentum: the 1991 liberalization of India’s economy, and the 2004 dismantling of the Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) quotas. Where others treaded cautiously, Shahi doubled down.

Today, Shahi’s footprint stretches far beyond Karnataka, with factories in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana. Still, Karnataka remains its stronghold, home to at least 40 of its 54 factories.

In 2014, Shahi made a bold move eastward, setting up a unit in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, with a capacity of 300,000 dresses per month and over 2,500 direct jobs. The state government, eager to boost textile employment, rolled out the red carpet. Plans for integrated textile parks in Chowdwar and Bhadrak soon followed, both of which are expected to turn functional in 2024-25.

While competitors remained confined or hit their peak, Shahi kept moving—threading ambition with strategy, one stitch at a time.

From Fabric to Fortune

What makes Shahi stand out in India’s crowded apparel landscape?

One of the key reasons Shahi succeeded where many others struggled is that it placed an early and unwavering bet on professional management.

While most Indian apparel manufacturers remain closely held and family-run, Shahi—though promoter-led—chose a more forward-looking approach. It prioritized merit over legacy, ensuring that key decisions were made by those with the right expertise, not just the right last name.

The company brought in professionals with deep technical knowledge and business insight in apparel manufacturing and textile engineering. These weren’t just top hires—they were nurtured, empowered, and given the space to grow.

Over time, this philosophy translated into a strong and scalable organizational structure. Shahi’s three major divisions—Ladies, Knits, and Men & Bottoms—function almost like standalone companies, each led by its own CEO, COO, and marketing heads.

This model of decentralization and empowered leadership has been a key differentiator for Shahi. Decisions are made faster. Projects move quicker. Lead times shrink. And because authority is distributed smartly across the hierarchy, the company remains agile even at scale.

Equally transformative was Shahi’s move toward vertical integration. Today, more than 80 per cent of its fabric needs are met in-house through company-run textile mills—a rarity in India’s fragmented garment sector.

That’s a big deal. Fabric alone makes up nearly half the cost of a garment. By producing its own, especially cotton and rayon (and now expanding into polyester and synthetics), Shahi not only slashes costs but also sidesteps supply chain bottlenecks that plague competitors.

Vertical integration has also made Shahi a favorite among global brands like Walmart, Gap Inc., Abercrombie & Fitch, PVH, Uniqlo, H&M, and Nike. These buyers value not just cost and speed, but traceability, quality, and supply chain transparency—all of which Shahi can offer from fibre to final product.

The People Behind the Process

At Shahi, the real engine of growth isn’t just technology or top-tier management—it’s people like Pushpa, whose stories define what the company truly stands for.

Married young and relocated to Bengal, life brought her back to Faridabad as a single mother determined to build a better future. A recommendation from a friend led her to Shahi. Twenty years later—with four promotions under her belt—she now leads a team of over 50 operators. Her eldest son, once a toddler she carried to her first job, is now juggling an MBA while working at a café.

Stories like Pushpa’s aren’t exceptions—they’re the result of a people-first culture that runs deep through Shahi’s DNA.

Since 2007, the company has partnered with initiatives like Gap Inc.’s P.A.C.E. program, which has empowered over 90,000 workers with personal growth, leadership, and life skills.

The impact goes beyond individual transformation—independent studies show the program has delivered a 250 per cent return on investment through improved attendance, engagement, and productivity.

In an industry often dominated by informal and contract labor, Shahi takes a different path. All its workers are permanent employees. That means job security, steady income, and the opportunity to grow—not just professionally, but personally.

Shahi’s investment in people pays off in more ways than one. Not only it furthers a sense of kinship amongst colleagues, but their word-of-mouth becomes a magnet for new talent.

The Lone Giant in a Shrinking Field

India should have ten companies like Shahi Exports. But the reality is starkly different. While manufacturing giants of Shahi’s scale are common in China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, they remain a rarity in India.

This is especially surprising given our demographic strength — over 950 million Indians, or about 67 per cent of the population, are of working age. On paper, we should have a clear advantage in labour-intensive manufacturing.

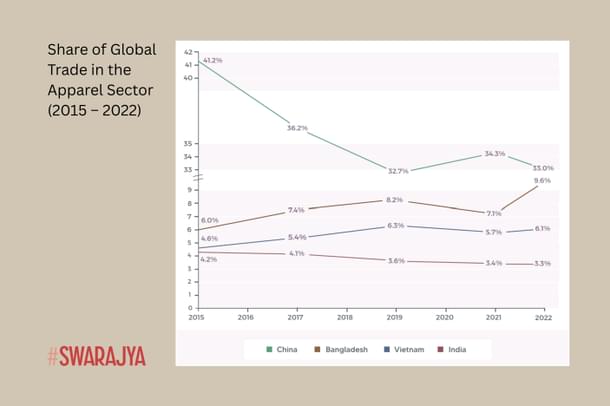

The last decade even handed us a golden opportunity. As China began retreating from labour-intensive industries, its global share in such products declined — creating a gap that countries like India could have filled.

But we didn’t. We let the moment slip through our fingers. The data speaks volumes: India’s share of global apparel exports fell from 4.2 per cent in 2015 to just 3.3 per cent in 2022. Meanwhile, Bangladesh has soared, growing its share from 6 per cent to 9.6 per cent. Vietnam, too, has expanded its footprint.

So what’s stopping others from following in Shahi’s footsteps?

Labour Labyrinth

The textile sector may no longer be a ‘reserved’ industry, but the ghost of old regulations continues to haunt it.

A bureaucratic jungle of labour laws—52 central acts, tangled further by a thicket of state-level rules make it difficult to hire workers or import essential raw materials—two fundamental pillars of any thriving apparel manufacturing operation.

Take the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947, for instance. This law mandates that companies employing 100 or more workers must secure government approval before initiating layoffs. In practice, this turns even routine business decisions into bureaucratic ordeals.

One more snag in India’s regulatory fabric is its inflexible stance on overtime. Under the Factories Act of 1948, there’s a strict cap on overtime hours per quarter—and employers must pay double the regular wage for any extra work.

The regulation designed to protect workers’ rights perhaps inadvertently hinder the growth of firms, especially small and medium enterprises, by restricting their ability to expand operations when needed.

For exporters, particularly large firms tied to strict international compliance audits, there’s little room to bend the rules. In contrast, informal sector firms often bypass these restrictions, and competitor nations like Bangladesh offer far more leeway, allowing manufacturers to operate with the flexibility global supply chains demand.

To its credit, the government has moved to untangle this regulatory mess. In an effort to streamline and modernise the system, it introduced four labour codes that consolidate 29 existing laws—aiming to drive growth through employment-led manufacturing, especially via MSMEs.

Although these codes have yet to be implemented, they signal a much-needed shift. For example, the Industrial Relations Code, 2020 merges three legacy acts—including the Industrial Disputes Act—and raises the threshold for mandatory government approval of layoffs from 100 to 300 workers. It’s a step in the right direction, offering more breathing room for growing firms.

Still, context matters. In countries like China or Bangladesh, a single apparel factory can easily employ over 10,000 workers. In that light, even a 300-worker threshold begins to look like a speed bump, especially for industries that thrive on scale.

And the compliance doesn’t stop there. Factories with 300 or more employees must still put in place detailed standing orders—covering everything from work classifications to grievance redressal—adding yet another layer of complexity.

No Hands On Deck

The irony doesn’t stop there. Even when firms want to grow or bring in investment, the process is anything but easy. India still ranks low on the ease of doing business.

Take approvals, for instance. While both India and Bangladesh take around 30 days to issue operating licenses, India drags its feet on construction permits, taking 35 days—more than double the 14-day turnaround in Bangladesh. It’s a small detail with big consequences.

And it’s not just the timelines. A staggering 25 per cent of senior management time in Indian export firms is spent wading through regulatory red tape. That’s one out of every four workdays spent chasing paperwork instead of chasing growth, innovation, or global clients.

Logistics is another Achilles’ heel. India’s supply chains are scattered and inefficient, pushing up costs and stretching lead times. It can take 90 to 120 days for Indian manufacturers to ship an order of 30,000 pieces. In Bangladesh or Vietnam? Just 14 to 21 days as their supply chain is more concentrated.

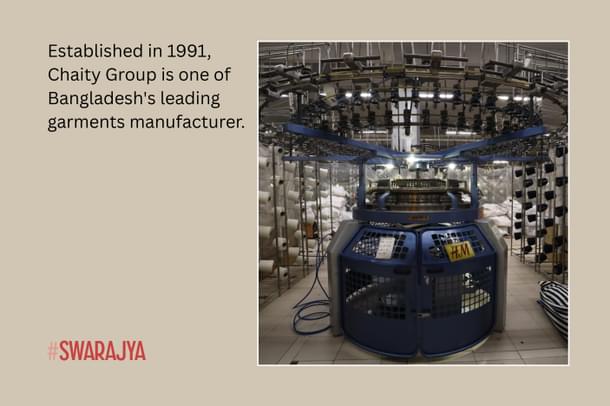

A big reason is lack of scale that has been enforced on the Indian ecosystem courtesy our laws. For instance, Bangladesh’s Chaiti Group, a supplier for H&M, operates around 5,000 machines under one roof, compared to 300-500 machines in factories located in Delhi- NCR, Punjab, or Tirupur.

And so, we come full circle. India’s regulatory burden continues to be the single biggest obstacle preventing investment in establishing large-scale apparel manufacturing capacities.

Missing the Global Bus?

India’s trade policy seems stuck in reverse at a time when the rest of the world is hitting the accelerator.

Instead of smoothly integrating into global value chains, India has tightened its grip on protectionism—hiking tariffs and erecting trade barriers, even as our apparel sector grows increasingly reliant on imported raw materials and intermediaries to stay competitive in export markets.

In 2021, we earned the dubious distinction of being the world’s “tariff king,” ranking fourth globally with average import duties at a steep 18.3 per cent. But here’s the kicker—high tariffs don’t just block imports; they ricochet. They inflate costs for Indian manufacturers, making our exports pricier and far less appealing to global buyers.

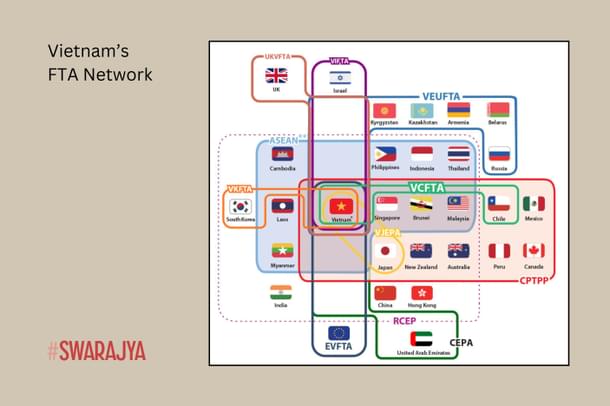

And just when the global trade tide was turning, we chose to swim against it. India has stayed out of key trade agreements like RCEP, IPEF, and Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) —deals that would’ve opened doors to the EU, the US, and beyond. Meanwhile, Vietnam, our fiercest competitor, holds membership in all three.

The consequences are writ large. India’s second-largest apparel exporter is only half the size of Shahi Exports; the third is just a third of its scale.

Everyone’s buzzing about the “China +1” shift. But while the world’s manufacturers are packing up and heading to Vietnam, Taiwan, and Thailand, India remains mostly a footnote in the relocation story.

Policy Promises, Patchy Delivery

Shahi survived—not by chance, but by sheer grit, smart reinvestment, and a sharp strategy of decentralization. It bent the odds in its favor. But let’s be honest: the road has been far messier than it should be.

Which brings us to the obvious question—where is the government in all this?

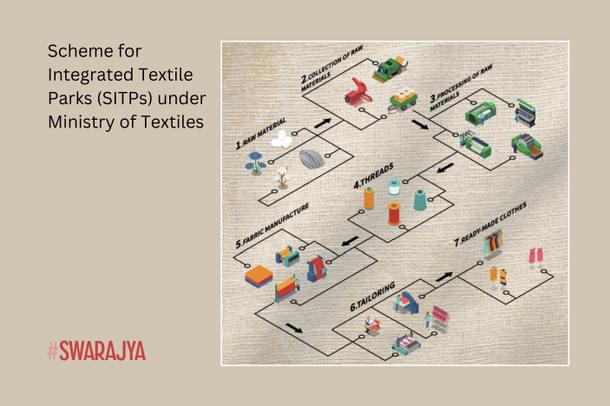

The support meant to boost the sector has, more often than not, missed the mark. Take the Scheme for Integrated Textile Parks (SITP)—designed to modernize manufacturing. Instead, most parks were far from urban centers, making worker access tough. Plus, they were too small—often under 75 acres—compared to global benchmarks of 150+ acres.

Then came the PLI scheme—great on paper, sure.

Launched in 2019 with a Rs 10,683 crore budget, it promised to turbocharge man-made fibre and technical textile production. But in reality, it felt more like a gated club. High entry barriers and narrow product coverage meant many manufacturers couldn’t get a foot in the door. Key textile categories were left out, and the investment-turnover thresholds were too steep for most to meet. Ambition wasn’t the problem—accessibility was.

Add to that sluggish disbursement of state-level incentives, and companies simply can’t afford to bank on these schemes.

Threads of Hope

In a country where nearly half the workforce is still tied to agriculture—a sector contributing less than 20 per cent to the GDP—the case for labour-intensive manufacturing isn’t just an economic argument. It’s a moral one. Creating dignified, stable, and scalable jobs is essential not just for growth, but for justice.

Shahi Exports isn’t remarkable only because of its billion-dollar revenue or its global clientele. It stands out because it dared to prove that scale doesn’t have to come at the cost of soul. That factories can be places of empowerment. That rural women can rise to lead production lines. That a young seamstress in Delhi can build something extraordinary—an empire that stitches livelihoods into lives.

“Shahi hain toh hum hain,” Saroj once told a researcher. “We are who we are because of Shahi.” In that single sentence lies the spirit of what meaningful manufacturing can look like in India—dignity at work, pride in contribution, and transformation through opportunity.

But Shahi’s story also highlights the roadblocks holding India’s apparel industry back. Despite our natural advantage in labour-intensive sectors, entrepreneurs still face a minefield of challenges—poor integration with global value chains, fragmented supply networks, complex regulations, and sky-high logistics costs. No wonder firms are either struggling, shifting focus, or looking beyond borders. Shahi’s scale is the exception, not the rule.

And yet, the tide may be turning.

In Bangladesh—India’s toughest apparel competitor—trouble is brewing. Political unrest, widespread labour disruptions, and natural disasters like floods have shaken the foundations of its apparel sector.

The resignation of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina following violent protests has brought many factories to a standstill, resulting in staggering losses estimated at $800 million (Tk 6,400 crore). On top of this, Bangladesh is preparing to graduate from its Least Developed Country (LDC) status, a move that will strip it of crucial trade privileges in markets like the EU and the US, making its garments less competitive.

This moment presents India with a rare and timely opening.

If—and it’s a big if—India can simplify rules, fix supply chains, and make doing business easier, it can finally step into the role it was always meant to play: the global hub of job-rich manufacturing.