Economy

Tariffs And Protectionism Are Not A Plan: India Needs Robust Industrial Policies

Rohit Shinde

Apr 20, 2025, 06:00 AM | Updated 09:54 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Industrial Policy (IP) is notoriously tricky to define. I’ll use the most common definition — IP is any policy that aims to transform the structure of the economy. That could be transforming an agrarian nation into a manufacturing one.

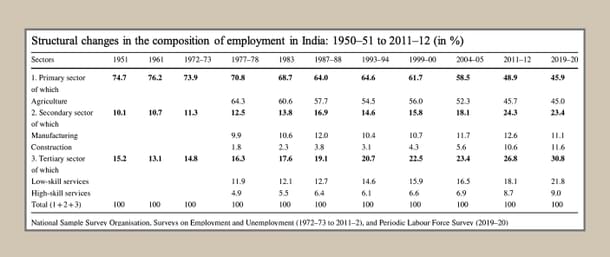

In India’s case, while agriculture contributes around 18 per cent of the GDP, it employs almost half the workforce. A well designed industrial policy could support labour intensive industries that move the workforce into manufacturing. Not having an IP is equivalent to having an IP for the current structure of the economy.

Even developed countries could use such policies. The US is infamous for regulations restricting land use, zoning and building. New York City couldn’t be built today the way it once was—40 per cent of its buildings wouldn’t meet current codes. And when you want to promote industries on the technological frontier — batteries, solar, drones, autonomous driving — there’s a lot to learn from Industrial Policy. I’ll give three examples:

1. Ronald Reagan — known for trickle-down economics and free markets — famously said “Government is not the solution to the problem, government is the problem”. But even he protected domestic steel and auto industries to encourage them to invest in technological upgrading.

2. President Pinochet of Chile was the posterboy for free markets. Even he promoted the forestry sector with immense subsidies. Unfortunately, the deleterious impacts of these policies on the environment are still being felt.

3. Margaret Thatcher, the British PM, was responsible for extending favourable terms to Nissan and getting it to open up their manufacturing shop in the UK. Honda and Toyota soon followed in the 1990s.

IP covers a large spectrum of policies. The most obvious are tariffs on imports and import quotas. They’re broad tools and usually end up hurting consumer interests.

There are also production subsidies like India’s Production-Linked Incentives (PLIs). Many countries set up Special Economic Zones (SEZs) where there’s a lot less regulation. China famously employed these SEZs in the southern part of the country for industrialization with Shenzhen being the most famous.

There are objections to IP, but they’re often based on empirical concerns rather than first principles. The biggest objection is often some version of “governments cannot pick winners”. And there are always partisans choosing their favorite successes or failures to make their point. There are successful examples of IP like:

1. The East Asian Tigers’ success is often attributed to correctly designed industrial policy.

2. China is often the flag bearer of industrial policy. Its SEZs, protectionism, state funding and export subsidies have vaulted it to the pole position in a number of frontier technologies, some of which include batteries, language models and autonomous cars.

3. Malaysia’s success in building a semiconductor industry successfully.

4. Brazil’s modest success in erecting a world class aircraft manufacturing industry.

5. Joe Biden’s CHIPS Act was successful in getting TSMC to build a manufacturing plant in Arizona and it recently started producing chips.

However, free market purists will point to other failures of industrial policy like:

1. The Concorde was the fastest airplane to hit the skies, covering the distance between London and New York in three hours. What started off as a joint venture between Britain and France, ultimately failed in making the airline commercially successful and it ended up being scrapped.

2. India’s many industrial weaknesses are a perennial source of failures despite successive governments encouraging industries.

3. Malaysia had a flagship state enterprise to manufacture cars known as Proton. Malaysia attempted to establish an internationally competitive car sector through the enterprise but was ultimately unsuccessful.

4. The US government provided Solyndra — a solar panel manufacturer — with over $500 million in loans to promote solar panel manufacturing and create jobs. Unfortunately, the company ended up declaring bankruptcy.

To ensure I am not attacking a strawman, I’ll include the strongest critique of industrial policy from the Hoover Institution:

There are two problems with industrial policy: information and incentives. Government officials don’t have, and can’t have, the information they need to carry out an industrial policy that creates benefits that exceed costs. Also, they don’t have the right incentives. If they spend literally billions of dollars of government revenue on buttressing an industry and the industry fails, they don’t suffer any personal wealth loss and don’t even lose their jobs. The only cost to them as individuals is their prorated share of tax revenues, which will typically be no more than a few hundred dollars. So what ends up happening is that subsidies and preferential treatment are given to the politically powerful, which reduces the amount of capital available for unsubsidized entrepreneurs and innovators.

And to be clear, this is a fair critique of IP. Taxpayer dollars are valuable and they must be put to good use rather than frittered away.

But as Juhasz, et al argue in their recent paper, “The New Economics of Industrial Policy”:

“But ultimately what is required for industrial policy to work is far less than a consistent ability to pick “winners.” In the presence of uncertainty, both about the effectiveness of policies and the location/magnitude of externalities, the ultimate test is not whether governments can pick “winners,” but whether they have (or can develop) the ability to let “losers” go. As with any portfolio decision, it would be an indication of sub-optimal policy if the government did not back some ventures that end up as failures ex post.

"In the U.S., Department of Energy loan guarantees to Solyndra, a solar cell manufacturer, failed miserably; but a similar loan guarantee to Tesla enabled the company to avert failure and become the behemoth it is today. In Chile, successes in four projects supported by Fundacion Chile – including most spectacularly salmon – is said to have paid the costs of all other ventures.

"Letting losers go may still be a hard task, in light of political pressures that inevitably develop. Indeed, Solyndra, for example, was backed by the government long after it became clear that the company would not become financially viable. But it is far less demanding than governmental omniscience. Ensuring that governments can stop backing evident losers requires a set of institutional safeguards that include clear benchmarks, close monitoring and explicit mechanisms for reversing course. [emphasis mine]”

In this day and age, with frontier technologies requiring massive capital and tight coordination between multiple industries, IP is required to solve any coordination failures. For example, an indigenous semiconductor industry may never develop because it wouldn’t be cost competitive initially. But if the initial learning could be subsidized, it may pay off in the future.

II

For Indians, Industrial Policy (IP) conjures images of the pre-1991 era with tariffs, import quotas, import substitution and the license-raj. With economic liberalization unleashed in 1991, India saw immense growth with economic strictures falling away. Since then, there’s been a consensus among a wide section of the Indian intelligentsia that the government’s involvement in industry caused the economy to stagnate. IP needs to be viewed through a different lens though.

As I elaborated above, as long as the policy design allows the government to let losers go and the government actually follows through, IP stands to benefit broader society. There are tons of benefits for India to have its own IP — I’ll list out three:

1. Any advanced technology requires tons of Research and Development (R&D). For any firm doing such R&D, there are technology spillovers into adjacent areas. For example, because of NASA’s moon mission, the world was able to get the benefit of freeze-dried food, aerodynamic swimsuits, memory foam, building shock absorbers and many more. These are global spillovers of R&D. The Internet itself wouldn’t exist without DARPA’s funding. India is the world’s largest arms importer and spends precious foreign exchange doing so. Funding an IP in defence would lead to saving aforementioned forex and help in exporting arms to other countries.

2. Coordination failures in moving to greener, sustainable technologies hamper adoption. For instance, solar has tremendous upsides but the initial cost of installation puts off many consumers. Solar panel manufacturers can never get the economies of scale needed to reduce costs. Government subsidies to manufacturers and consumers — a form of IP — can help out here.

3. Some parts of India are backwards due to various socio-economic reasons. Setting up industry there would provide a much needed source of jobs. Since industry benefits from clustering effects, being the first company to set up shop in such areas would face problems in recruiting talent — among others. IP is a great tool to use to subsidize such costs.

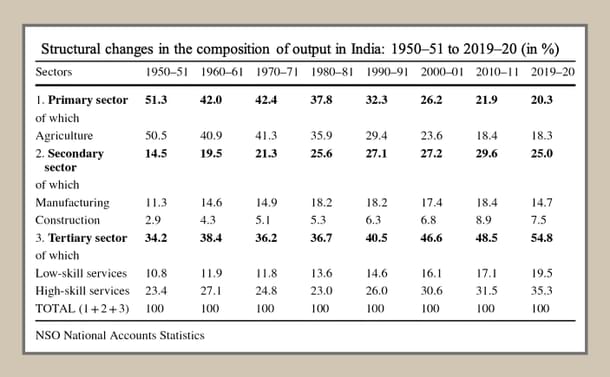

India was forcibly deindustrialised through colonisation and the initial decades since independence bear that out. Agriculture contributed to half the GDP and employed three quarters of the workforce. While agriculture’s contribution to GDP has come down over the decades, there’s still half the workforce remaining in agriculture.

Services have been contributing most to GDP in recent decades, accelerating since the 1991 reforms. Services can’t be mass employers unfortunately. Even body shops like the Indian IT services can’t employ as many people as a textile company can.

Sadly, manufacturing hasn’t been able to improve its contribution to the GDP. PM Modi’s aim is to increase manufacturing’s contribution to Gross Value Added (GVA) to 25 per cent. So far it hasn’t borne out. There are various reasons for this, ranging from labour laws to difficulties in getting access to factor inputs.

Successful industrial policies for India must reshape both employment patterns and the broader economic structure.

Approximately 12 million people join the labour force every year. Ideally, a few million would be moved away from agriculture and into more productive manufacturing or service jobs every year. The Labor Force participation Rate (LFPR) for India stands at about 58 per cent compared to almost 75 per cent for the US. Bringing that up to developed world standards would involve creating a few million additional jobs a year. That means India is looking at the formidable challenge of generating about 16 million jobs a year.

III

If you’ve read this far, hopefully I’ve convinced you of the need for an aggressive industrial policy.

Contrary to public opinion, Nehru’s socialist model with its focus on heavy industries wasn’t really as big a failure as imagined publicly.

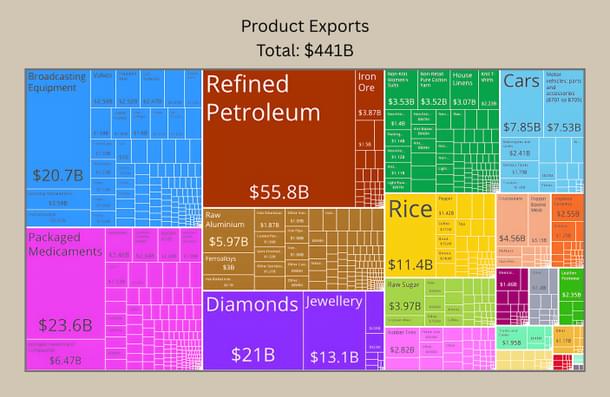

Using SITC data, Felipe, Kumar and Abdon (2010) show that for a country at its stage of development, India has a highly sophisticated export basket. Despite India’s comparative advantage being labour intensive products, it has done very well in capital and skill intensive markets. The Nehru-Mahalanobis model of development invested in capital heavy industries with moderately successful outcomes.

I’ve (not so) subtly blamed tariffs and other protectionist measures throughout this post. But that’s not the whole story. China is famous for its heavy protectionism. Yet, it still managed to join the ranks of upper middle- income economies.

America has a long history with protectionism too. Britain aggressively pursued protectionist measures in the late 19th and early 20th century. There are other examples of the developed West dabbling with protectionism. If protectionism was undesirable and free trade was the be-all and end-all, these countries wouldn’t have developed.

Free trade provides an impetus to development, but even without it, countries can develop with good policies. The free trade consensus of the early 1990s and 2000s was seen as hollowing out America, leading to the rise of Trump’s terrible tariff regime.

So what other policy held India back?

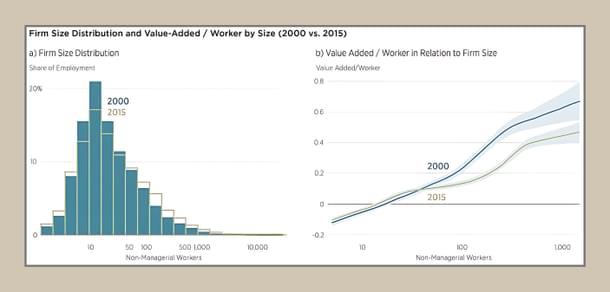

The answer to this: The Small-Scale Reservation Policy (SSRP). Under this policy, certain items were reserved to be manufactured exclusively by the small scale industry.

How did the government define small scale?

By the amount of capital a firm had invested. The limit was Rs 1 crore in 2015 (about US$150,000) and has now been revised to be Rs 10 crore.

By 2002, there were around 800 items reserved exclusively for this sector. Over the next decade, they would slowly be whittled down, until in 2015, the last 20 remaining items were dereserved as well.

The downsides of this policy were immense.

Any firm specializing in these items couldn’t organically grow otherwise it would be disbarred from producing them. Large firms couldn’t leverage economies of scale to produce the items at a lower cost. Small firms were prevented from naturally expanding into other areas because they couldn’t compete with larger companies on non-reserved items.

Depending on the method of measure, if India hadn’t adopted such a policy, its manufacturing sector would have seen an aggregate increase in Total Factor Productivity (TFP) of 40-60 per cent between 1987-1994.

To put this into perspective, if capital and labour in the economy remained constant and everyone’s productivity grew by 50 per cent, the GDP itself would grow by 50 per cent. With capital and labour entering the Indian economy during that period, the growth would have been even faster and India might have joined the ranks of upper middle- income economies by now.

IV

So what does successful IP look like for India? What are some concrete policy suggestions and what roadblocks need to be removed?

Free the Labour

Labour laws are the metaphorical thorn in the foot for the country’s enterprises.

Any company above 300 employees requires permission from the government for retrenching its workforce. It shows up as 92 per cent of firms in the country having less than 100 employees. This statistic also implies that firms probably employ more labour on a contractual basis. Sen, Saha and Maiti provide evidence in support of that. I covered labour laws in more detail in a previous post.

India has a Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) in labour intensive sectors. Comparative advantage is the principle that a country (or person) should specialize in producing the goods or services it can produce at a lower opportunity cost than others. Even if one party is more efficient at everything, both sides can still benefit from trade by focusing on what they give up the least to produce.

RCA is a metric that shows whether a country is relatively better at exporting a particular good compared to the world average, offering a practical way to observe comparative advantage through trade patterns.

Exploiting this RCA is important to generate the 16 million jobs that we calculated earlier.

Policy Coordination

There’s a tendency to view IP as a single policy. In reality, it is a bunch of policies closely tied together that offer some concrete benefits. While subsidies and export support are common tools, there are other policies that need to be worked on.

For example, to export more textiles, India needs more ports and highways to reach those ports from manufacturing regions.

Similarly, getting better at state- of- the- art semiconductor manufacturing requires clean air and water. Even a speck of dirt in a manufacturing facility can cause an entire batch of wafers to be thrown away. These aren’t traditionally thought of as IP, but some industries can’t exist without it.

Many Indian states have electricity utilities managed by the state government. Often used to grant favours to key constituents by politicians, they run into massive losses. In such cases, industry is the first to suffer because they have minimal votes. Without electricity generation, the best IP won’t be able to attract companies. And even if it does, it won’t be able to keep them.

The DARPA Model

The US has had tons of R&D spillover from DARPA. The Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) sets up problem statements in frontier technologies, invites companies to apply and then funds the most promising applications.

The list of its impact is long and includes the Internet among others. GPS was a DARPA project too! There are many failures here, but the successes have been spectacular. If there wasn’t DARPA, there might not have been a Google Maps.

The learning here applies to India too. With the Army importing a large amount of arms, not only is this needed to reduce imports and save foreign exchange, it is an absolute imperative for national security.

There have been positive steps taken by the government in this regard and Big Bang Boom Solutions has been one of the success stories. These policies need to be stepped by an order of magnitude.

Embedded Autonomy and learnings from Peruvian Mesas

Often, there’s been (well-meaning) suggestions that industry and government should have a barrier to prevent stigmatized and crony capitalism from taking hold. It is well intentioned, but ultimately this approach is doomed to failure.

The state is often sufficiently independent to act purposefully but without input from broader society, it cannot gain necessary information sitting in its ivory tower.

To have the best chance of success, an IP should adopt the structure of Embedded Autonomy. Put forward by Peter Evans, it argues that any successful state intervention has two components:

1. Autonomy, where the state is empowered to act in its long term interests without undue influence from pressure groups.

2. Embeddedness, where it establishes dense, concrete connections with elites and entrepreneurs through which it accesses critical information and develops a forward thinking entrepreneurial class.

This idea is bold and very ambitious for Indian society which is riveted with divisions — primarily caste and religion. But walling off the state from society will lead to ineffective interventions. Without such embeddedness, the flow of information between bureaucrats and firms stops. That’s disastrous because there’s often informational asymmetry in this relationship.

A good working example of an upper middle income country that practiced this with good success comes from Peru. Peru established mesas that put this concept in practice. It is a good example of building durable industrial policies in lower-capacity environments.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs)

SEZs are a common policy suggestion so I won’t spend a lot of time on it. Essentially the government sets up a geographic area where the trade and business laws are different from the rest of the country.

They’re effective when business friendly reforms are politically impossible in the entire country, so the government creates a smaller area where business is easier. GIFT in Ahmedabad, Gujarat is a recent example of such a SEZ.

To be really effective, there must be only a few such zones and they must be big to allow clustering of firms to occur.

India has about 300 such zones. That’s ineffective. China has fewer zones and people know the most famous by name — Shenzhen. And here, India doesn’t even have to do anything innovative. Simply copy China’s playbook modified to Indian environments.

Free Trade

As Trump has shown with his tariffs, free trade is extremely important. While protectionism isn’t the death knell to development, it makes it harder. Tariffs are a blunt tool for protectionism. They don’t have automatic sunset measures. Once put in, they’re extremely hard to remove. A political lobby forms around the tariffs and pushback against reduction is extreme. This is evidenced from the US steel sector.

Importantly, no country on the face of the Earth is self-sufficient in everything. Intermediate inputs are required for all industries and tariffs make them expensive. Counterintuitively, they make the end products more expensive for the domestic consumer. The consumer doesn’t have a choice, and the industry becomes uncompetitive internationally with its higher prices. It would be unable to expand into international markets.

India still has relatively high tariffs. That makes the cost of its end products more expensive to users. The free trade regime that started in the 90s did more to improve consumer welfare in 10 years than the tariff based regime did in the 40 years since independence.

There is ample evidence that trade liberalization and specialization gradually moved India from low-tech sectors to more complex ones. Industries that faced the largest tariff reductions have seen the largest improvements in trade specialisation. Individual firms might be hurt, but the overall sector prospers.

Production-Linked Incentives (PLI)

PLIs offered subsidies for hitting production targets for participating companies. Applicable to 13 sectors — textiles, semiconductors, batteries and solar among them — it aimed to boost production and knowhow in these technologies.

The one crucial element it lacked was an export subsidy. However, the goal wasn’t for the companies to export, but to expand nationally and increase production. It was wildly successful in getting the semiconductor industry into India.

In other sectors though, it achieved limited success before being withdrawn. Mainly, it involved multiple agencies coordinating along with turf wars. Pranay Kotasthane has a good writeup on the topic so I won’t repeat the analysis.

As an industrial policy, I appreciated the PLI scheme, but until underlying factor markets are improved, such schemes will continue to have limited success.

V

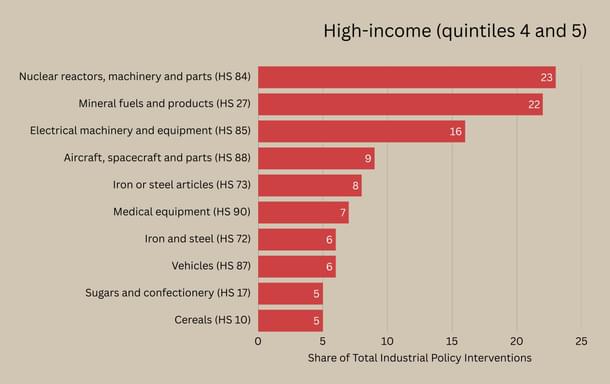

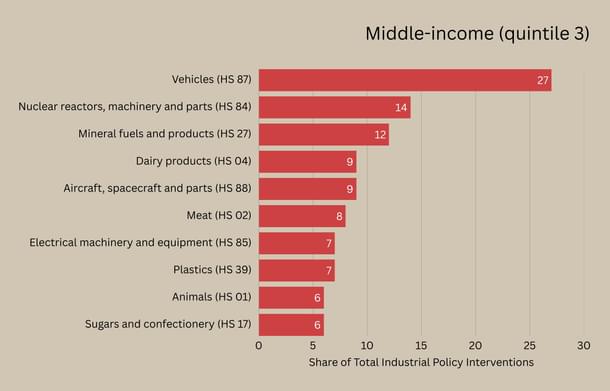

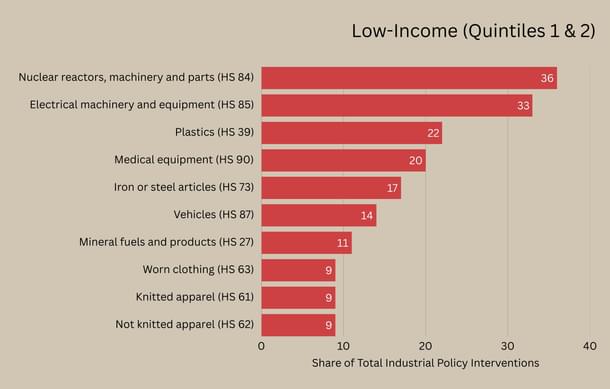

There’s a whole bunch of reasons to be optimistic about Indian manufacturing and its exports. India’s exports (shown below) have high economic complexity compared to its per capita income. However, this can improve even more by adopting targeted industrial policies.

The biggest problem India faces right now is dualism. An informal sector employs the majority of the workers, but is low on productivity whereas the formal has high productivity but employs less workers. This drags down the TFP of the economy, reducing growth.

Workers aren’t part of the tax net and subsequently lose out on welfare schemes. Firms don’t get benefits of formalization and are forced to remain small.

With good IP, these problems can be resolved and TFP growth can really accelerate. Growing TFP is the most essential since it measures the efficiency of resource usage to produce an output.

GDP can grow by applying more inputs of labour, land and capital. The more land you throw at agriculture, the more will be the output. But after some time, you run out of land. That’s when how land is used matters. In the lLong term, only TFP growth will allow India to join the ranks of developed nations.

Originally published on Rohit Shinde’s Substack.

Rohit Shinde is a software engineer based out of the US. He likes keeping up with the latest research in economics and applying it to problems in India. He posts on X from @rohitshinde121.