Heritage

Why Researchers At Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Won’t Rest For The Next 100 Years

Sumati Mehrishi

Mar 10, 2019, 05:32 PM | Updated 05:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A century has turned away like pages of a loaded chapter at Pune’s Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI). The institute, a great confluence of oriental studies, turned 100 in 2017. A new circle of count and another century has begun. BORI's work on classical texts and scriptures is leaping into another phase.

It is home to a grand agglomeration of reference archives on oriental studies, yet, researchers and scholars are working every minute to fulfil their vision of making BORI a monumental bureau of 'literary advice and information' in all spheres of oriental studies.

The quaint campus stands against the screech-and-scratch of urban noise — a contrast to its existing photographic memories in standalone sepia. It does retain the old charm of being a breathing repository of heritage born in Poona (now Pune), in 1917.

BORI's 100 have given India and the world the flowing resource of literary heritage for thousands of years to come. It is not the kumbh, but the ghat.

Its manuscripts resource and conservation centre falls under the National Mission for Manuscripts. Last year, BORI opened its treasure of invaluable text source in an e-library in its first phase of digitisation, and it aims at digitising all manuscripts housed here.

When I visited BORI last year, the only sign of celebration of a remarkable century of work was researchers and scholars engrossed in more work, studies, research and explorations of texts and manuscripts.

BORI is home to a mammoth collection of rare manuscripts. This treasure is the second facet of heritage. The first facet of heritage is the campus itself. Layers of heritage within heritage, text on ancient texts, make it more than a mere 'institute'.

While the first phase of digitisation serves the natural purpose of preserving the oldest texts in the repository, it also opens around a 1,000 rare books and manuscripts in Sanskrit and related languages to readers online.

Some challenging projects are still under progress. Professor Ganesh Umakant Thite, with a team of research scientists, is continuing the work of compiling a dictionary of the Prakrit languages, which has been on since 1988 — five volumes published so far.

Time is clocked in the striking of a metal gong at BORI’S premises. But there is one more way to measure time at BORI. It is viewing how years would have rolled by, in the backdrop of BORI’s monumental service towards providing texts, sharing perspectives on publications, studies and researches, which have either been carried out at BORI, or BORI has been involved in. Great scholars and minds — from Lokmanya Balgandhar Tilak to professor Vishwa Adluri have pored over works emanating from, preserved at, or published here.

The music of its printing press is history. The printing equipment from its illustrious past would find new audience. Instrumental in making BORI’s esteemed publications, some the best attainable, available to scholars across the world, it would be a part of a museum at the campus. Time is clocked in heritage concealed within heritage. Time is being clocked against new tasks undertaken.

The team of researchers at BORI has begun preparing basic material for further studies. Something revolutionary is taking place in silence. BORI is currently working on producing a cultural index of the Mahabharata based on the critical edition, among other projects.

Shrikant Bahulkar, honorary secretary, a scholar in vedic and Buddhist studies, Ayurveda and classical Sanskrit literature, tells Swarajya, “we want to collect the information on various topics, like names of different personalities in Mahabharata, names of trees, mountains, geography, history, philosophical tenets and so on. Once we collect this information, that will be the basis for future studies.”

When BORI researchers talk about their work and milestones covered by it, I notice that the effort gone into these tasks and projects is understated. The immense volume of work involving the many mammoth projects is spoken about in a breeze. It's a prominent sign of sincerity that defines researchers here.

Mention ‘Arjun’, and a peculiar celebration in their voice strikes you. Throats melt. Thite, the dedicated veteran scholar, is one of them.

He says, "Arjun is one of the most important characters in Mahabharata. You will find so many references to him in the epic. Under the cultural index, we are concentrating on the numerous personalities and references, in the Mahabharata. This will be done in alphabetical order. For example, when we are exploring 'a', all references to characters beginning with 'a' will form a collection. References on Arjuna and Abhimanyu will be collected. Each aspect will be covered in a fascicule. Each fascicule published will be about 100 pages."

BORI researchers and scholars see Mahabharata at the core of BORI's work and history. "It is the heart and soul of BORI." It is also collaborating with the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies on a project on the Bhagavata Purana.

The institute, named after Dr Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarakar, the revered pioneer of scientific orientology in India, has connected the world to Indic knowledge, providing ground to Indological studies and research, provided texts, the premise, and pillars to criticisms, interpretations, translations, new texts, putting before scholars its work on Mahabharata, ancient manuscripts, and preservation of the most delicate, brittle and precious facets of heritage.

The beginning was made by Dr Bhandarkar himself, who laid the foundation for the Critical Edition of the Mahabharata. Thite says, "thousands of manuscripts in different scripts containing different number of verses were collected from India. Besides his work on the Adiparvan, Bhandarkar wrote a very detailed introduction to the problems existing and the solution to those problems in the field of work on Mahabharata. The Critical Edition of the Mahabharata was not end of the work. It was the beginning of the work."

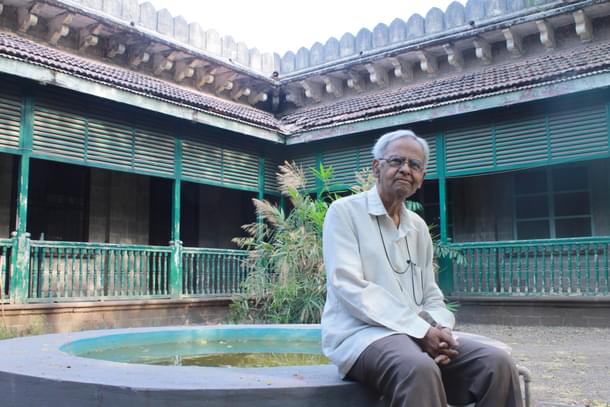

Sparing a few minutes from his desk for a picture under the afternoon sun, Bahulkar goes back in time. "After its inception, the institute immediately took up the project and worked for 50 years — meticulously. There are around 1,600 manuscripts, out of which, scholars collected 734 manuscripts of variety, various scripts written in various periods of time — broadly divided into southern and northern region of the Mahabharata and they brought out a critical edition of the text consisting of around 85,000 verses."

In 1966, BORI reached a milestone that would define its work and contribution among scholars of oriental studies and Indology around the world. It presented its Critical Edition of the Mahabharata — a textual one — in 19 volumes. The project raised a monumental benchmark for scholars exploring the critical study of the great epic.

Bahulkar counts its completion as one of the biggest milestones at BORI. "It is one of the biggest achievements because of the immense work and research methodology gone towards it. It is a big contribution to the world of oriental studies and Indology," he says.

This edition, according to him, is a landmark in the field of "what we call Indian textual criticism". It was completed on 22 September 1966. He proudly adds, "some scholars in foreign countries had already attempted this, but they found it very difficult and gave up the idea of bringing out a critical edition."

BORI's work on the epic has been acknowledged by scholars, researchers worldwide and students and research scholars in India. Bahulkar says, "The Critical Edition of Mahabharata — a treasure of critical material on the epic, was prepared with painstaking efforts to become a prestigious and appreciated editorial work. It is a milestone undertaken by BORI since its inception."

Bahulkar tells us that thousands of manuscripts were studied and interpreted for the task. The methodology applied had to focus on oral text. It had to be different from the methodology applied to written texts.

The scale of work and material was huge, and it set high standards of research for world scholars. "The credit for it goes to noted scholar V S Sukhtankar. He was well versed in Sanskrit and textual criticism, principles of editing, German and other languages, but he realised that the principles of textual criticism in the West, which were applied to the Bible and other ancient texts, Greek and Roman texts, cannot be applied in to this epic (Mahabharata).

And, that we cannot use the same methods of research as used in the study of written scripts in the West. He developed Indian textual criticism. This was a landmark. This work was completed on 22 September 1966. Dr S Radhakrishnan had come to grace the concluding ceremony that took place here at the institute," Bahulkar adds.

Another milestone of BORI is Bharat Ratna Pandurang Vaman Kane’s individual work History of Dharmasastra, published here. It runs in five volumes and is one of the most popular works among scholars even today. "He spent his whole life for this monumental work and single handedly prepared the history of Dharmashastra," Bahulkar adds.

At his desk, Thite goes through some pages of work being done under the cultural indexing of Mahabharata. He is shouldering a big task. The ongoing work of the cultural index to the Mahabharata is being done under his guidance. He says, "the compiling and editing of entries for Mahabharata's cultural index is a challenging task and it must continue. It throws open the treasure of numerous aspects in Mahabharata and of the great epic, including details related to all aspects. Arjun, himself, is a vast subject of study. And that is just one aspect I am naming. Cultural indexing will throw open a vast ground of culture, history and cultural history. It will also see us working on the rivers in Mahabharata."

The mysteries, matter and material of time, histories and cultures, live in manuscripts preserved and kept at BORI's manuscript hall, which is an enormous space, home to silence and scripts. Here, treasured manuscripts, more than 29,000 and counting, rest on clean shelves. Wrapped in red cloth — they come across as sacred artefacts hidden from the world outside.

These preserved manuscripts are symbols and holders of a continuing tradition. The red cloth envelopes history, histories and cultures. And the red cloth provides a protective layer to the tangible heritage — brittle, but breathing. The red wrap clothes a rich past living in scripts and languages. Amruta Natu, assistant curator in charge, describes red around manuscripts as "tradition". She says, "generally, white cloth is used as well. But we mostly use red."

Natu sits amidst heritage. She guards it firmly, even against my camera. The volumes of text placed on her sturdy desk, and it is here she whispers some facts to me. "There are 28,000 manuscripts, mostly in Sanskrit; around 4,000 manuscripts in Prakrit "related with Jainology".

She adds, "manuscripts are written in various Indian regional scripts, like in Bengali, Kannada, Telugu, Tamil. Then, there are manuscripts written in various material. There are palm leaf manuscripts. There is a collection of Kashmiri manuscripts as well, really precious ones. The oldest dated manuscript, 906 AD — it is a Jain narrative called Upamitibhavaprapanchakatha, it is on palm leaf and the oldest dated paper manuscript dates back to 1320 AD — a medicinal treatise — Chikitsasarasangraha."

The red cloth lends colour to antiquity. It, however, doesn't succeed in containing the fragrance of this invaluable heritage. It manages to escape. Among the preserved manuscripts here are also some rare ones — in scripts Devanagari, Sharada, Oriya, Bengali, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil. The silent shelves speak languages Sanskrit, Marathi, Arabic, Persian and Urdu. "Among these, there are also around 1,500 which contain miniature paintings, and around 150, on birch bark," Natu adds.

So far, nearly 10,000 manuscripts have been digitised. Natu hopes that all will be digitised. "This is a treasure that we have been preserving since the last 100 years. The catalogues would be placed on the website."

There are 300 manuscripts which are related to Ayurveda and medicine. Students pursuing studies in Ayurveda visit the institute and consult these manuscripts regularly. "When you see the whole class of Sanskrit literature, there are more texts related to poetry, poetics, drama, dramaturgy and rituals," she adds.

The rich repository consisting more than 28,000 manuscript, received 17,000 — which traveled from Elphinstone College, Mumbai, to Deccan College, Pune. Mumbai’s climate was not favourable to their preservation and the manuscripts collected under the Indian Manuscript Collection Project, eventually found home at BORI.

"Part of the valued collection is the collection of 838 manuscripts brought from Kashmir. These are birch bark manuscripts in the Sharada script. They are a great source for knowing Kashmir’s history. Then, there is a Rig Veda manuscript — part of the collection which was sourced from Kashmir. There are 5,000 manuscripts in Prakrit languages," Natu adds. The Rig Veda manuscript is listed by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) under its Memory of the World programme." Dating to 906 AD, it is one of the oldest in BORI's treasured collection.

For Natu, work includes guiding visitors, guiding field of subject, answer queries on typography, calligraphy, various courses deliver lectures, universities, how to read manuscripts procured, purchased or copied. The interesting part: BORI is training people to turn preservers.

"For the last few years, we have not approached people who collect manuscripts. This is because of limitation of resources. Another major reason is that we are a part of national mission for manuscripts. We are one of the manuscript resources and conservation centres. Under that project, we are working to guide people to preserve the manuscripts where they are. We approach people or staff in institutes to preserve manuscripts, so, we don't encourage even private collectors or general public to donate the manuscripts to us."

What is the way out? "We'd prefer to educate them (towards manuscript preservation). However, if they are not willing to keep the manuscript at their home or collection, then we preserve and keep those manuscripts," she adds.

The descriptive catalogues of manuscripts in the government manuscripts library of BORI are another facet of its contribution. According to researchers here, the entire collection has manuscripts which were collected since 1866, so, the first descriptive catalogue (of manuscripts related to vedas) was first published in 1916.

Natu adds, “since then, the institute is working on cataloguing the manuscripts. There are 20 planned categories or subjects, like manuscripts related to vedas, vyakarana, Ayurveda, etc. Out of 20 volumes, around 16 have been published. We are working on the rest. There are experts related to various subjects who are helping us."

According to Bahulkar, BORI's ongoing work in publishing research papers and inspiring the setting up of libraries, making accessible rare and treasured manuscripts to research scholars is strengthening its roots for the journey ahead.

He adds, "research projects and publications is one activity. Also in progress are annals and journals of BORI."

Existing for 98 years out 100 of BORI, its annals are time tested and famous medium for scholars from around the world to publish their work. Per year, editors select a few quality research papers, essays and books from around a 100 BORI receives.

The new entries are meticulously reviewed. "The weight of contribution from stalwarts and gurus such as Dr S K Belvalkar, Dr A D Pusalkar and Dr R N Dandekar, among others, who were also editors of BORI's annals, makes the texts authentic, respected and trusted the world over," Thite adds.

The annals travel from BORI to research institutes outside India. The flow, back and forth, between India and other countries continues as the institute receives research papers published in international journals. "The library offers these journals and research papers to people and scholars for a very affordable fee," Shreenand Bapat, curator in charge, says.

Senior scholars Swarajya met at BORI believe that the work undertaken at BORI will continue, but must involve new challenges, new research in Indology, more scholars and new realms of approaches and growth.

Bahulkar adds, "unfortunately, in India, oriental studies are restricted to Indology, and Indology is mostly restricted to Sanskrit, but we are expanding our area beyond Sanskrit studies. We want to pursue our activities in the field of Indology, consisting of Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, various religions of India and schools of philosophy, also, Indology, ancient history and culture."

According to him, in 100 years, BORI has managed to build free academic exchange and interaction across faculties.

Meanwhile, rare unknown texts, contemporary texts and texts on texts come out, and keep flowing into BORI. According to Dr K K Jain, who is currently heading the department of the Prakrit dictionary, BORI would be able to 'widen horizons' by looking at the neglected areas. "We are thinking of establishing centre for Asian studies and to begin with we would take up some projects related to Tibetan, Chinese and Japanese studies — mainly textual and cultural studies," he says.

The source material for the Prakrit dictionary “has been collected in an archive of over 600,000 reference slips", Jain looks back. He says, "in 1987, the institute undertook another project, that is critical and comprehensive dictionary of Prakrit languages like Ardhamagadhi, Shauryaseni and other major languages, which existed in the ancient and medieval period in various parts of India. It was supported and funded by the trust run by Navalmal Kundanmal Firodia — freedom fighter and a great man."

BORI's internationally-recognised library named after Dr R N Dandekar includes around 20,000 rare books among its collection of 125,000 on orientology — "some of these belong to the early days of printing", as Bahulkar puts it.

According to scholars here, more than 2,000 books were donated by Bhandarkar himself, and personal collections of stalwarts of oriental studies, such as A D Pusalkar, R N Dandekar, P V Bapat and P L Vaidya, are part of the esteemed edifice.

The extent of work and contribution from scholars involved with BORI can be roughly understood by the fact that their work is part of the collection, and books from their personal collection part of what scholars from all over the world now refer to.

There is another facet to it: books written in honour of committed scholars at BORI, like Thite ji himself. There is Self, Sacrifice and Cosmos: Vedic Thought, Ritual and Philosophy (Essays in honour of Prof Ganesh Umakant Thite's contribution to vedic studies), authoured by Lauren M Bousch.

Collaborations and collections point at an exchange flourishing as a facet of Indian soft power. Among the books fairly fresh in the collection are: The Seventy-Five Elements (Dharma) of Sarvastivada in the Abhidharmakoshabhashya and related works. Buddhakosha: A Treasury of Buddhist Terms and Illustrative Sentence (Vol. VI), and another book on Dharmakirti's Theory of Exlusion, published by The International Institute for Buddhist Studies, Tokyo, among others.

BORI is South Asia's biggest repository of ancient texts, and there is not a trace of pomposity to the building, exterior or interiors. It bears a low profile. The Indo-Islamic architecture wears meditative silence. The silence is broken by Pune's traffic outside the campus, and beautifully paused, by the striking of the metal gong, that sees scholars breaking for a short tea.

BORI has been the cradle of texts reaped from our civilisation. The Critical Edition of the Mahabharata, Critical Edition of the Harivamsha were completed in 1966 and 1969. September provides a rhythm to the completion of the great tasks undertaken here. According to Bapat, it is to mark, symbolically, the time of the year when BORI remembers the man who started the institute and the movement. "Bhandarkar ji's punya tithi falls in September," he says.

BORI's generosity is perhaps known by scholars in India and the world over, who have been able to turn the tide of their own literary works, research and explorations propelled by the texts opened and provided at BORI. I was able to get a glimpse of this generosity during my first visit. Bapat and Bahulkar ji were quick to tap my interest and thrill surrounding BORI's print and publishing heritage. "The press unit leaves a different aspect to BORI's heritage. You must see it next time you are here," they say.

Natu connects over her fascination for an artefact in BORI's collection — terracotta tablets dating back to sixth century BC. She says, "it is the oldest artefact in the collection. And to me, the depiction reveals that a kind of licence was given to her, during or for her travels, perhaps. These tablets — Assiriyan tablets in cuneiform script, were found in Mumbai."

Thite ji gives a glimpse of pages of cultural indexing and mentions quickly and briefly all aspects related to ecology, nature, women and men, that the cultural indexing of Mahabharata is unraveling to him and his team. "If you are serious about cultural history, culture and history, you will find all the important aspects related to them in Mahabharata's cultural index," he concludes.

A lifetime is short to be able to hold a part of what BORI has collected, assimilated, converged and shared in its 100 years. However, a beginning can be made into its next set of 100 by engaging with texts — in the quest for texts, cultures, histories, languages, and scripts, and over to the depths in Mahabharata.

For that one needs to engage with and support BORI. So that another 100 — of time clocked between Lokmanya and Adluri, also sees a Sukhtankar. Until then, the manuscripts must stay preserved — sacred and safe —in red cloth. So should Dr Bhandarkar's vision of BORI.

Pictures: Sumati Mehrishi

Sumati Mehrishi is Senior Editor, Swarajya. She tweets at @sumati_mehrishi