Ideas

How Hindu Rights Have Been Seriously Damaged By Article 30 And RTE Act

Sanjeev Nayyar and Hariprasad Nellitheertha

Dec 16, 2019, 04:40 PM | Updated 04:12 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

We are repeatedly told that all Indians are equal before the law but not told how some laws apply unequally to the majority community. The right to managing educational institutions is an example.

Article 30 (1) of the Constitution states: “All minorities, whether based on religion or language, shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice”.

What Is The Background To Article 30?

The initial draft versions of the Indian Constitution prepared by Dr K M Munshi had proposed explicit, and equal, educational rights to all communities. However, when this section was referred to the minorities sub-committee of the Constituent Assembly, what came out was a very different version.

It read:

All minorities, whether of religion, community or language, shall be free in any unit to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice, and they shall be entitled to state aid in the same manner and measure as is given to similar state-aided institutions.

The origin of Article 30 lies in the discussions held primarily in the Second Round Table Conference held in 1931. It was derived from the memorandum submitted by Indian Christian representatives then. The version of the clause in the memorandum actually asked for “equal rights for all religions”. However, in the joint agreement version, that particular phrase was left out.

Therefore, Indian Christians, whose schools received preferential treatment during British Protestant rule, wanted special rights to continue after Independence (the co-author of this piece went to a convent school that started around 1870).

When the Constitution was adopted, the majority community was anyway expected to enjoy complete freedom in matters of culture, religion and educational rights. Alas! That was not to be.

This article looks at various provisions of Article 30 and the Right to Education Act (RTE), their interpretation by courts and how they have been implemented. It is presented in a frequently-asked-questions (FAQs) format for easy reading.

Article 30 provides similar benefits to religious and linguistic minorities.

The first question is who is a religious minority? The Indian Constitution does not define the word ‘minority’ and assumes that Sanatana Dharma is an organised monolith like Abrahamic religions, based on one book and one founder.

In 1950, religious minority meant Muslims, Christians and Parsis. Today it includes Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains. The Constitution does not specify a population percentage beyond which a community ceases to be a minority. This is absurd for it means even at 500 million, Muslims would still be considered a minority because their population is less than that of the Hindus.

This lack of definition has resulted in quaint situations. In Punjab, Sikhs constitute more than 50 per cent of the population but are considered a minority for the purposes of Article 30 since their population, on an all-India basis, is less than that of the Hindus. Ditto for Muslims in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir or Christians in Meghalaya or Nagaland.

Next, who is a linguistic minority? Since the creation of linguistic states, a community whose mother tongue is the language of the state is the majority and the others minority.

So, a school started by a Gujarati-speaking Hindu in Maharashtra is a linguistic minority because Marathi is the language of the state. If the majority of the trustees of a charitable trust that run a school in Maharashtra are Gujaratis, the school is deemed to be run by a linguistic minority. Needless to say, this provides scope for misuse.

What Is The Current Scenario?

Over time, courts received numerous cases relating to educational rights, and passed judgements interpreting the provisions of the Constitution from the point of view of the majority and minority communities. Here are some significant court orders and their impact.

Q1. What type of institutions can be started by minorities given protection under Article 30 (1)?

According to ‘Kerala Education Bill’ judgement, the Supreme Court, in 1958, made it very clear that Article 30 (1) allows minorities to open and run “any kind of institution”. There are no limitations placed on the subjects to be taught in such institutions, and a particular religion or language may or may not be taught.

The SC judgement said,

In other words, the Article leaves it to their choice to establish such educational institutions as will serve both purposes, namely, the purpose of conserving their religion, language or culture, and also the purpose of giving a thorough, good general education to their children.

Thus, minorities can open schools, colleges, management institutions, medical colleges, etc. It will be deemed a minority institution if the religion or language of the management is minority. It does not matter if the nature of the institution has no relation to preserving the minority community’s culture and religion.

Does this not put the majority community at a disadvantage?

Q2. Do minority institutions teach or evaluate in a different way?

Notwithstanding the special rights, minority institutions teach the same way and evaluate using the same tools. In the ‘Ahmedabad St Xavier’s College….’ case, the Supreme Court said:

With regard to affiliation to a University, the minority and non-minority institutions must agree in the pattern and standards of education. Regulatory measures of affiliation enable the minority institutions to share the same courses of instruction and the same degrees with the non-minority institution.

Q3. Since the rights under Article 30(1) are meant to further the religious and cultural aspirations of minorities, one would assume its students are limited to those belonging to the minority community that runs the institution.

No. A minority institution can admit students from all communities. It does not have to admit a pre-determined percentage of students from that community to qualify as a minority institution. The courts support this view.

In the ‘TMA Pai Foundation vs Others 2002’ Case, the Supreme Court quoted one of its earlier judgements in the matter and stated:

…The real import of Article 29(2) and Article 30(1) seems to us to be that they clearly contemplate a minority institution with a sprinkling of outsiders admitted into it. By admitting a non-member into it, the minority institution does not shed its character and cease to be a minority institution. Indeed, the object of conservation of the distinct language, script and culture of a minority may be better served by propagating the same amongst non-members of the particular minority community…

Does the order tacitly support the propagation of religion by minority communities?

What is a good percentage in terms of ‘outsiders’ versus ‘insiders’ is left to individual state governments to decide. The figure for minority community students in Karnataka is a maximum of 25 per cent and in Maharashtra 50 per cent. It is doubtful if these percentages are in the public domain and monitored by state governments.

Thus, we see that in this market segment of ‘education’, the majority and minority communities are operating on the same material (institutions), performing the same processing (teaching, standards, evaluation) and delivering the same products (graduates) and yet only one market operator — the minorities — get special privileges. More about this later.

The British created a concept of majority and minority that does not exist in their country. They sowed the seeds for discrimination against the majority community that the Protestant majority does not suffer from in England. This idea of giving specific concessions to minority communities that do not apply to majority communities is, to the best of our knowledge, not found in any country.

Q4. Like Article 30(1) for minorities, do Hindus have similar rights?

The Supreme Court has on various occasions said that non-minority communities derive a ‘similar’ right from Article 19(1) (g) of our Constitution which gives every citizen the right to carry on any occupation etc. Article 19 reads:

“Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech etc

(1) All citizens shall have the right

(g) to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business”

However, the difference between the two sources of rights is that while Article 30(1) is unhinged and carries no exceptions, Article 19(1) (g) has a restrictive clause under Article 19(6) that imposes certain restrictions on the rights and reads:

(6) Nothing in sub clause (g) of the said clause shall affect the operation of any existing law in so far as it imposes, or prevent the state from making any law imposing, in the interests of the general public, reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub clause, and, in particular, nothing in the said sub clause shall affect the operation of any existing law in so far as it relates to, or prevent the state from making any law relating to, (i) the professional or technical qualifications necessary for practising any profession or carrying on any occupation, trade or business, or……

Since 1950 governments have, supported by the judiciary, used Article 19 (6) to bring in laws that control each and every aspect of establishing and administering majority community educational institutions.

Why is the majority community being denied the right to conserve their language, culture and religion?

Q5. What are the rights that minority have, but majority community institutions do not have?

In the ‘TMA Pai Foundation vs Others…’ judgement, the Supreme Court has listed these rights.

“50. The right to establish and administer broadly comprises of the following rights, i.e. to:

(a) Admit students

(b) Set up a reasonable fee structure

(c) Constitute a governing body

(d) Appoint staff (teaching and non-teaching), and

(e) Take action if there is dereliction of duty on the part of any employees.”

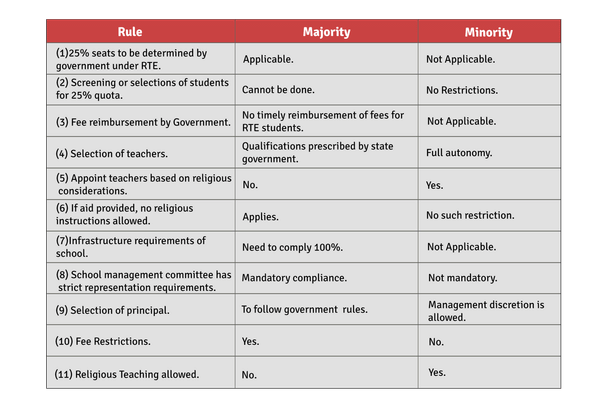

The table below compares rules for majority versus minority community educational institutions.

Let us look at some of these rights in some detail.

1. What does right to admit students mean?

This involves the type of students being admitted and the procedure to admit them to the institution

One, minority institutions need not reserve 25 per cent of the seats under the Right to Education (RTE) Act. Conversely, Hindu schools have to do so. The RTE was held to be valid by the Supreme Court in the ‘Pramati Educational Society’ case in 2014.

Why is the responsibility for educating children from the economically-weaker sections of society placed on the majority community alone?

Two, there is a huge disparity in the procedure to be adopted with respect to selection of students.

Section 13 of The RTE Act says:

No capitation fee and screening procedure for admission: (1) No school or person shall, while admitting a child, collect any capitation fee and subject the child or his or her parents or guardian to any screening procedure.

It means that an RTE-compliant institution cannot screen any child to determine whether or not he/she will fit well into the school for students admitted under the RTE quota. A Mumbai-based school administrator told this author that many parents moved their children out of their school due to the poor quality of students admitted under RTE. It is not that the school did not want to take students under RTE, but there has to be a profile match.

Minority institutions have always enjoyed complete freedom in selecting students. This has been highlighted by the Supreme Court in the ‘Sindhi Education Society Judgement:

A minority institution may have its own procedure and method of admission as well as selection of students, but such a procedure must be fair and transparent, and the selection of students in professional and higher education colleges should be on the basis of merit.

The words fair and transparent allow scope for misinterpretation and abuse.

As a result, minority institutions have freedom to select students that are not available to non-minority institutions.

2. How are schools paid for students taken under RTE?

There is invariably a large gap between expenses incurred and reimbursements by state governments. Reimbursements are not prompt either.

In February 2019, over 4,000 schools threatened a one-day bandh in Maharashtra due to a delay in the reimbursement of student fees to schools.

The state government tried to reduce its liability by modifying the norms for RTE reimbursement stating that “if a private school is using any government land and benefiting from the same, then the school would not receive reimbursement for students who have been admitted in the 25 percent RTE quota,” says a Mumbai Mirror report.

A Mumbai-based school was told that it could claim exemption from this provision if it paid property taxes in excess of Rs 1 lakh per year.

Delays in reimbursements adversely affect school cash flows, increase costs and puts them at a disadvantage as compared to minority community schools. Members of the majority community complain why so few schools are run by them and most are unaware of this discrimination.

Q3. How has RTE negatively affected Hindu schools?

According to the trustee of a Mumbai school that belongs to the majority community,

The number of students is restricted to 40. The subsidy does not cover all expenses. There is no clarity on what is covered under subsidy, for e.g. books, uniforms, fees for additional facilities, sports, etc. This leads to constant arguments with the education department who advice parents to demand the same from schools inspite of the department not being clear on the matter. If parents do not pay, the school has to bear the cost as you cannot single out these students.

There is no clarity on how the fee subsidy is fixed. It allows unfettered intrusion and interference by the education department and parents. It is very difficult to expel students for harmful activities, bad behaviour, etc. Vacancies on account of shortfall (difference between the 25 percent quota and the actual admissions taken under the quota) in the number of RTE students cannot be filled up at all, so seats remain vacant. This results in financial loss for majority community schools.

This is also a national loss as some students lose the opportunity to learn in private schools, which are better than government schools.

Why must schools of the majority community be discriminated against like this?

4. Right to appoint teaching staff.

In Maharashtra, majority community schools are given a copy of Teachers Rules Handbook. The name of the book by which they govern secondary schools is called SS Code. The minority community has to adhere to this only if they receive government aid. Further, state governments can transfer surplus teachers from one aided school to another without consulting management.

Also, according to a March 2018 Madras High Court order, irrespective of whether the institution receives government aid or not, teachers in schools run by minorities are exempt from the Teachers Entrance Test (TET). In short, teachers of majority community schools have to go through TET but not minority-run ones.

Minority institutions have complete autonomy in the selection of teachers, the only restriction is that the process must be fair and transparent — a subjective judgement, to say the least.

The Sindhi Education Society judgement elucidates on this matter as well:

…in the matter of day-to-day management, like the appointment of staff, teaching and non-teaching, and administrative control over them, the management should have the freedom and there should not be any external controlling agency. However, a rational procedure for the selection of teaching staff and for taking disciplinary action has to be evolved by the management itself…

Conversely, state governments have made laws detailing multiple qualifications for the appointment of teaching staff to educational institutions. Majority community-run institutions have to strictly adhere to these norms.

According to the trustee of a school in Maharashtra, all schools can fire teachers after conducting an inquiry as mandated by the law. But except for aided schools, the education department is not involved.

He adds that generally education laws in Maharashtra are applicable to every school, but the education department is reluctant to challenge the minority schools or take action on complaints. Also, all boards make it compulsory to adopt state qualifications for teachers. So indirectly, it is applicable to minority schools also.

When there is no standardisation of teacher qualifications, can the quality of teaching be consistent?

Further, a minority institution can appoint a teacher for a secular subject based on religious considerations, whereas a majority community-run institution cannot do the same, even if it intends to further the cultural and religious education of Hindus.

For example, in a minority school, even a teacher of mathematics or science can be selected in such a way that their adherence to the religious principles of the particular minority is taken into account.

On the other hand, no Hindu school can make choices of similar teachers involving any religious or dharmik factors.

This makes it difficult for Hindu-run schools to teach their culture and religion, and children grow up in a cultural void.

This is one of the many reasons why those who want to seriously study or teach Sanatana Dharma migrate abroad, mostly to the US, because there is freedom to learn and a better appreciation of Indian thought in that country.

4. Right to appoint management (principal)

Article 30 (1) provides minority institutions with a large amount of flexibility in the matter of appointment of a principal or headmaster.

The Supreme Court ruled thus in the ‘The Secretary, Malankara Syrian….’ Judgement:

Section 57(3) of (the Kerala University) Act (1974) provides that the post of Principal, when filled by promotion, is to be made on the basis of seniority-cum-fitness. Section 57(3) trammels the right of the management to take note of merit of the candidate, or the outlook and philosophy of the candidate which will determine whether he is supportive of the objects of the institution.

Such a provision clearly interferes with the right of the minority management to have a person of their choice as head of the institution and thus violates Article 30(1). Section 57(3) of the Act cannot therefore apply to minority-run educational institutions even if they are aided.

Only a minority institution can appoint a principal keeping aside concerns of seniority and merit in order to further the objectives of the institution.

One wonders why the principals of majority should be controlled by state laws when the same does not apply to those run by minorities.

5. Restrictions on Fees

Hindu schools have to get their fee structure approved by the state education department. Unaided schools do not require prior approvals from the state government for fixation of fees. If the increase in fees is challenged by the parents, then procedure laid down by the law is followed. In practice, minority school parents do not complain about increases in fees.

6. Right to provide religious education

Article 28 of the Indian Constitution states that no religious instruction shall be provided in any educational institution wholly maintained out of state funds. Simply put, no government school can provide any religious education.

Whenever the government provides aid to a Hindu-run institution (even private), the same becomes ‘aided’, thus teaching ‘religious practices’ is disallowed.

Conversely, when the same government provides aid to a private minority institution, it does not stop it from teaching religious principles and practices.

What is difficult to fathom is this disdain for teaching of Sanatana Dharma in educational institutions by those who drafted and interpret the Constitution. No wonder children grow up without an understanding or appreciation of Indian culture and thought.

Even if a government school has 100 per cent Hindu students, it cannot provide any religious education to them.

On the other hand, even if a minority institution has only 1 per cent of the student body belonging to the actual community, it can still offer religious education to all students belonging to any religion. This continues even if the said institution is aided significantly by the same government!

7. Based on Article 28, can the state government deny aid to a minority institution because it imparts religious education?

The Constitution, however, prohibits such a possibility through Article 30(2), which reads:

The state shall not, in granting aid to educational institutions, discriminate against any educational institution on the ground that it is under the management of a minority, whether based on religion or language.

Other Regulations For Hindu Schools

Hindu-run schools face multiple other regulations for which individual states have prepared rules — for example, mandatory requirement of a certain amount of real estate, infrastructure, sports and play equipment, compulsory establishment of libraries, setting up of school management committees with 75 per cent representation from parents etc.

Being exempt from the above, minority institutions have complete flexibility to set up any kind of educational institution — from a budget school to a premier institution.

In case of mismanagement in a majority community institution, the state can appoint an administrator but not if the school is a minority institution. Further, the state cannot insist on having its own nominees on the managing body in case of a minority institution. It has become difficult to ensure security of tenure to teachers in minority institutions.

Net Impact Of Article 30 And RTE

One, numerous Hindu-run institutions face threats of closure due to excessive government regulations. Many institutions, especially schools, have indeed closed down.

Two, RTE has given the Christian minority a disproportionate advantage in the education sector. First, they inherited the management of schools set up by the British. Second, they get freedom under Article 30. Third, those who wrote the Constitution did not visualise large funding from multinational Church-based organisations.

For example, the Ryan International Group of Institutions, founded by Dr A F Pinto in 1976, has over 130 institutions today in India and abroad.

We sent a questionnaire to Madam Grace Pinto, managing director of the Ryan Group, on various aspects of Article 30, including how much of this success would you attribute to your being a minority educational institution?

Her office responded, “Thank you for your email. However, we would not like to be part of this questionnaire. Hope you understand.”

A similar questionnaire was sent to the principal of Cathedral and Sir John Connon School, Mumbai, on 7 November 2019 (founded in 1860), but we are yet to receive a response.

By virtue of being a part of a global church network, Christian schools receive foreign donations. For example, the Tirunelveli Diocesan Trust Association received Rs 3.72 crore in 2015-16 and the Warangal Catholic Diocese received Rs 2.89 crore in 2016-17.

Did those who drafted the Constitution and interpret it visualise that Article 30 would be used by the minority community to set up a huge business and receive foreign funding from multinational church organisations to set up schools?

Three, minority schools are useful in facilitating religious conversions.

This is what Arihant Pawariya wrote in Swarajyamag.com with respect to the admission process in the Central Entrance Test (CET) for BEd courses in universities and colleges of Andhra Pradesh. The Supreme Court stated in its order of 25 September 2019 that “67 out of 200 students in New College of Education, Nizamabad, 90 out of 136 in Rayalaseema College of Education, Kurnool, etc, were admitted on the basis of Baptism Certificates. In most of these cases, the candidates declared themselves to be Christians subsequent to the date of submitting their applications for the Entrance Test.”

Former Infosys director T V Mohandas Pai wrote in Economic Times, “Two house maids who converted said that the school where their children went raised fees and due to their inability to pay they were told they would waive it if they converted (which they were forced to do). Of course, the school was rabid in their evangelism with these children.”

And these are only a few instances.

Four, slowly and steadily, institution building is slowing down amongst Hindus. Without institutions, Hindu society becomes weak — culturally, spiritually and educationally.

Five, communities resist being labelled as Hindu because of excessive government control. No wonder an institution as respected as the Ramakrishna Mission petitioned the courts in the 1980s that they are not Hindus.

Dr S Radhakrishnan, former President of India, wrote in ‘Recovery of Faith’, page 184:

When India is said to be a secular state, we hold that no one religion should be given preferential status.

Today, all excluding the religion of the majority community are given preferential status.

Article 30 must, therefore, be amended immediately and all sections of Indian society must be granted equal rights for running educational institutions.

Let us hope that in the near future, Article 30(1) of our Constitution shall read as follows:

All citizens shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

Those who speak about minority rights must read what the Supreme Court judgement in Mudgal vs Union of India (1995 SC 1531), para 35, had to say:

Those who preferred to remain in India after partition fully knew that the Indian leaders did not believe in the two-nation or three-nation theory and that in the Indian Republic there was to be only one nation – the Indian nation – and no community could claim to remain a separate entity on the basis of religion.

Is there any country in the world where the majority community is discriminated against like this?

Was the purpose of Article 30 to give minority institutions unbridled rights to set up educational empires and support conversions?

When there is so little freedom given to Hindu schools in education, will not the quality of education suffer?

Has not Article 30 led to a serious study of Indic faiths outside India rather than in India?

The Indian educational sector is divided into majority and minority institutions, one subject to excessive control and another to minimal government control.

Sanjeev Nayyar is a Chartered Accountant and founder of www.esamskriti.com. Hariprasad Nellitheertha is a software professional who is interested in spirituality, and law, and writes occasionally on these topics.