Ideas

How Indore Became India’s Cleanest City

Ekta Chauhan

Feb 05, 2018, 07:42 PM | Updated 07:42 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

As I landed in the city on a dusty October afternoon, I had expected a typical Indian city with litter by the side of the road and more than a few overflowing sewers. But, well, I was surprised. Madhya Pradesh’s largest city has also become India’s cleanest – and it’s not a sight to be missed.

While in Indore, you cannot escape two things in particular about the city – the smell of the delicious street food and the bright yellow cleaning trucks playing the “Swachh Indore” jingle as they go about their daily cleaning routines. The everyday efforts of the city government as well as the citizens to maintain cleanliness is both admirable and inspiring.

Indore was declared as the cleanest city according to Swachh Survekshan 2017, an initiative of the Urban Development Ministry. The path to the top has been a long and hard one for the city, but the Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC) has ensured that solid long-term plans – and not quick fixes – were adopted to address the city’s problems. The IMC, which governs 85 wards and a population of over 27 lakh people, implemented a series of carrot-and-stick measures over the last year that has led to the position the city finds itself in now. The city has swiftly moved up from its 149th rank in 2014 to the top of the ladder this year.

The IMC especially placed great emphasis on waste segregation and door-to-door collection. So instead of “adding” dust bins, the city moved towards the more novel concept of a binless city, and removed over 1,400 bins. Earlier, in the absence of door-to-door collection, residents had no choice but to put their garbage in plastic bags and then throw them into public dustbins – more often than not, throwing the bags around the bin rather than inside it. As a result, heaps would accumulate over days with strays and rag pickers taking out their due share and leaving the rest of the surroundings unpleasant.

Removal of dustbins thus also reflects the success of door-to-door collection. Smaller litter bins have now been placed for pedestrian use. This writer herself went with local municipal officers on two drives in Sarafa and Indira Nagar, and the precision and dedication of all those involved deserves applause. Sarafa, popular for its delicious street food, was also known for its dirty streets littered with food packets, plastic bottles and other such items. Having travelled to various cities, I had also made my peace with dirty, old city quarters that you had to brave if you wanted a taste of the local culture. But not here; every shop has two separate bins, and the wait is diligent for the municipal truck to come for the evening collection drive. Some of the owners would specifically point towards the dustbins while they returned my change, and ask me to dispose dry and wet waste separately.

While the IMC has levied heavy fines on those caught littering the roads to discourage the practice, incentives have been offered for those doing good work as well. A discount of 5-10 per cent was offered on property tax to those who installed bulk waste converters to compost organic waste. Many hotels grabbed the opportunity and now operate waste converters on their premises. For those who do not have the space to accommodate an organic waste converter, a waste collection fee ranging from Rs 2,000 to Rs 5,000 was charged every month.

To further encourage participation, the IMC incentivised innovative solutions and practices through competitions and awards from the mayor and the municipal commissioner. We had the opportunity to interact with some of the officers and ground staff from the health department of the IMC and each one’s dedication was admirable. Most of the “darogas” go on their daily patrol early morning with their wireless device and constantly keep a track of all the municipal trucks and sweepers; the exercise almost reminds you of a military drill.

There are constant drives to make citizens aware of the health hazards of spitting, public urination and littering with the help of radio FM, TV advertisement, jingles and newspapers. Slogans have been painted on 1.5 lakh square metres of wall space across the city too. It’s hard to see a wall without a message painted. And the impact of this massive campaign is visible. During my four-day stay in the city, I could hardly see anyone littering or urinating in public.

The city’s residents proudly flaunt their city’s rank on the cleanliness index. Ramesh Kumar Chopra, president of Residents’ Welfare Association of the upmarket area of Indira Nagar, even claimed that Indore’s streets are now better than those in most Western countries. During our brief discussion over tea, he gave credit for the success of this mission to the efforts of local municipal officers as well as the guidance provided by the city mayor, Malini Gaud.

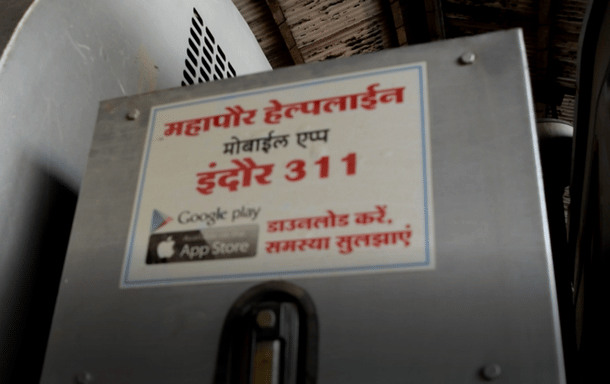

Much of the credit for the success of Indore’s cleanliness mission has been given to its current mayor. She has been taking personal interest in the city’s hygiene and it is reflected in her initiatives, like the Mayor Helpline and App (available in English as well as Hindi for local use). On our interaction with health department officials, we were told that citizens could lodge a complaint about issues related to cleanliness in their area, and most of them were resolved within 48 hours. The app receives a range of complaints from breakage in community toilets to overflowing dustbins, which are then directed to the mayor’s office for prompt resolution.

Collecting garbage from every household is, however, only one aspect of the mission, the other being keeping the public areas clean. Main roads are swept thrice a day instead of twice as in most cities. Mechanical sweepers are used every alternate day. Roads are washed every night using pressure jets with the aim to make the city “dust-free”, a task that may sound impossible in other Indian towns.

The trucks themselves are cleaned regularly and one would hardly find the trench associated with such vehicles (and those who work for them). We accompanied one such truck to find out where the garbage was being dumped. The trenching ground once again is a sight difficult to see in any other city in India. After the garbage is cleaned and sorted, composting is done simultaneously and used to develop green belts around the dump.

Indore has successfully set itself apart from the usual lack of political will and blame games among different departments. The “foreign-like” state, as said by a number of its residents, is not only the result of technology and the manpower employed, but also the collaboration between the government (at both the state and city levels), non-state actors (non-governmental organisations and commercial establishments) and citizens. The slogan “milkar ye sankalp kare, Indore ko swachh banana hai” (let’s pledge together to make Indore clean) beautifully captures the spirit of the drive.

Ekta is a staff writer at Swarajya.