Ideas

Pedagogy Of Oppressed: Decoding The Legacy Of West Bengal Violence

Sumit Gupta

Jun 17, 2019, 04:39 PM | Updated 04:39 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The violence in West Bengal has always been romanticised by the demagogues. In an unfortunate continuum of extreme violence, Bengal’s politics has been spearheaded by Trinamool Congress, which paints a very gory picture of the state. Several incidents are responsible for perpetuating the violence under which the whole of West Bengal burns. In one of the recent instances of violence, various parts of the city of joy plunged into an unabated turmoil, triggering a string of accusations from Trinamool without any concrete evidence.

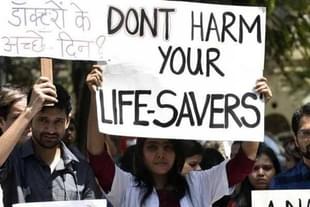

However, violence has become commonplace for the people West Bengal to face such inferno. Every day, we hear news about scuffles in eastern India that ultimately lead to widespread violence. In one of the recent incidents, doctors in Kolkata protested against an unfortunate incident wherein, two medical professionals were assaulted at Nil Ratan Sarkar Medical College and Hospital allegedly after a 75-year-old patient succumbed to his condition on the night of 10 June.

The patient’s kin blamed the medicos for negligence after which a mob of more than 200 people attacked the junior doctors at the hospital. The incident has led to intense protests by doctors that first started in Bengal and then spread across the country. The inadequate and, to many medical professionals protesting or otherwise, unacceptable response of West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee further angered the doctors, who have refused to call off their strikes despite an ultimatum.

Before continuing further, let us look at the rise of Banerjee in West Bengal. In December 2006, she waged a 25-day hunger strike to condemn the attempt by the West Bengal government to forcibly acquire land from farmers to build an automobile factory in the state. Similarly, in 2007, the then Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) government led by Buddhadeb Bhattacharya decided to turn the region of Nandigram into a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). About 10,000 acres of land was to be acquired for chemical industrial purpose. But, the local peasants of Nandigram agitated against this government move.

In that situation, Banerjee rose to prominence by championing the cause of the peasants of Nandigram. It was in her protest rallies in the region, where she made the war cry of maa maati manush (mother, motherland and people). Her agitation forced the CPI-M to drop the SEZ plan and abort the strategy of evicting the Nandigram peasants from their land. She became the hero for farmers, who were being oppressed by the then government. She led from the front, thus ultimately establishing herself in Bengal’s politics. She freed the oppressed peasants from the vicious clutches of the oppressor. Therefore, it can be conclusively said that she was an eclectic woman who fought for the cause of peasants, working class, and at the same time talked about development.

But, the reverse psychology consumed West Bengal politics after she came to power in 2011. Once in power, she became the perpetrator of the very violence she stood against. Under the garb of championing a cause, she became an autocratic leader, who rules the state with an iron hand.

For example, in the panchayat elections of 2003, 11 per cent of the seats were uncontested, in the 2018 elections, 34 per cent of the seats were won uncontested by Trinamool, which is evidence of the dominance wielded by the ruling party in these elections. Nothing really changed except the party banner under which violence is now being perpetrated. Worse still, with the CPI-M and the Left Front government gone, the crucial element of political management of large-scale violence and conflicts rests with Trinamool Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party (a nascent party in West Bengal).

Against the backdrop of these developments in Bengal, there arises a curious question. What led the intellectuals, students and people of West Bengal to take up the route of violence? Why violence has become a part of the Bengali psyche now? Why the oppressed became the oppressor after acquiring power? Why West Bengal is burning in reverse psychology of fear and violence? These became the natural questions as the people engaged in clashes are essentially from Bengal.

To understand the curious case of Bengal, we can take cue from Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire. He explains the relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor. On the one hand, despite the immense weight of oppression, the oppressed still militate against the unfreedom that they find themselves caged in; on the other hand, under years (sometimes generations) of subjugation they ‘internalise’ the image of the oppressor.

The oppressors, thus, ironically, become the model of humanity for them. And they are torn between their inherent need for liberation and their desire to mould themselves (their way of thinking, their belief system, and their ethics) in the cast crafted by the oppressors; and thus, to identify with them. The oppressed after getting liberated become the oppressors and thus this vicious cycle of widespread subjugation continues.

West Bengal politics is in the grip of this vicious cycle. Singur, Nandigram and Lalgarh incidents propelled Banerjee to power but ironically she began to oppress with the same intensity as the capitalists and industrialists who suppressed the peasants of the state.

The book by Freire is relevant for the political scenario of West Bengal wherein large-scale hegemony exercised by the oppressor leads to the oppressed internalising a similar image. The oppressed have begun to identify themselves with the oppressor and thus even after getting liberated from the oppressor, they (oppressed) adopt the lifestyle of the oppressor. It becomes a usual practice for them. Their judgement gets clouded by the continuous struggle and thus they tend to forget the cause for which they stood for. The culture of violence has in no way retreated. It only changed hands.

Political violence has always been an integral part of Bengal’s history. The forms of such violence – over time – have mutated and transformed themselves. In delineating diverse aspects of the state’s legacy of violence, the oppressed thus becomes the oppressor who revolve around political parties and aim at controlling the electoral turf, which in turn stands in sharp contrast to the philosophies that spurred the earlier forms of violence the state had witnessed.

The recent scuffles and unabated violence cannot be directly attributed to Banerjee. It is the effect of reverse psychology which ought to be blamed partially. But, in the end, it is still in the hands of Trinamool, which regulates the democracy and political structure in the state.

It is still in the hands of Banerjee on how she perceives this challenge of reverse psychology and thus establishing herself as a political stalwart or becoming a rabble-rouser, which completely destroys the very purpose for which she stood for in her days of struggle to power. The extension of the olive branch to the doctors is one such move from Banerjee. Let’s see how these incidents play out in the upcoming assembly election.