Ideas

Superficial Similarities And Profound Differences: Why Hindutva Must Reject The Trappings Of Western Right

Aravindan Neelakandan

Sep 21, 2025, 07:00 AM | Updated Sep 20, 2025, 09:48 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

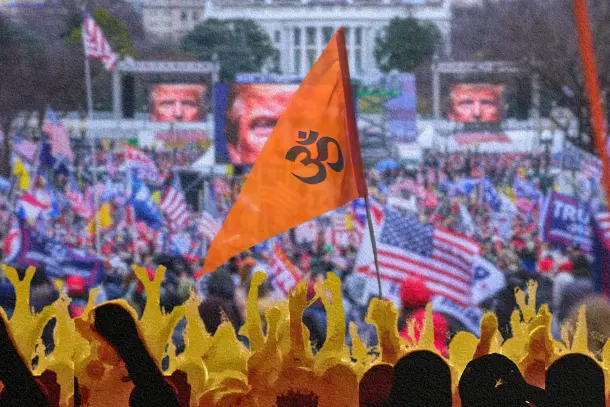

The rise of right-wing movements in the West seems to echo, for some, the nationalist assertions of Hindutva in India.

This perceived alliance, built on a shared critique of globalism, woke kind of liberalism, and Islamist extremism, presents a tempting proposition: a global front of cultural conservatives.

But this alignment, however tactically appealing, is a profound ideological trap for the Hindutva movement. Especially because it rests on a false equivalence, conflating the deep, pluralistic civilisational currents of Hindutva with the exclusionary, often racialised, nativism that animates much of the modern Western right-wing.

To navigate this perilous landscape, proponents of Hindutva must look to their own complex history and the diverse figures who have engaged with the idea of being Hindu.

In the oceanic churn that happened in the first half of the 20th century, two Westerners who chose each an entirely different Indian path, in their own perspective, offer starkly contrasting archetypes that serve as a crucial guide:

Satyanand Stokes born Samuel Evans Stokes (1882-1946), the American Quaker who became a Vedantic-Hindu freedom fighter, and

Maximiani Portaz (1905-1982), the French-born Greek-Italian Nazi sympathiser who took the name 'Savitri Devi' and tried to create an imagined bridge between 'Hitlerism and Hinduism'.

Stokes's journey embodies a genuine synthesis rooted in service and Darshanic harmony, while what Savitri Devi represents is a grotesque appropriation, a colonisation of Hindu symbols for a supremacist European ideology.

Their divergent pathways are not mere historical curiosities; they represent two fundamentally different paths, two irreconcilable visions of what it means for Hindu Dharma and society to engage with the non-Hindu world.

The choice between the path of Stokes and the trap of Maximiani Portaz is the critical challenge facing Hindutva today.

Samuel Stokes to Satyanand Stokes

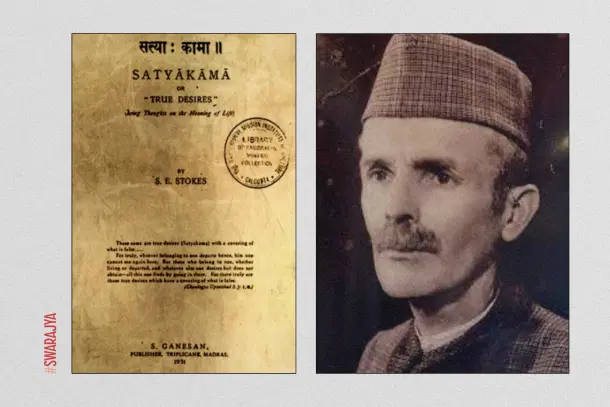

The journey of Samuel Evans Stokes is a powerful testament to a journey of profound identity dissolution and reconstruction. He arrived in India in 1904 as a young American Quaker with a missionary's zeal, but his complete immersion in Indian life systematically dismantled the inherited framework of his Western, colonial, and evangelical identity.

His first disillusionment with the racial baggage of the colonial Church prompted him to shed his Western markers and adopt a life of austerity. This commitment soon evolved from evangelical 'charity' to a formidable campaign for social justice, as he led the fight against the exploitative begar system, moving from addressing symptoms of suffering to confronting its structural causes.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre shattered his faith in British rule, propelling him into the heart of India's freedom struggle, where he became the only American to serve on the All India Congress Committee and was jailed for sedition, earning Mahatma Gandhi's deep admiration.

Parallel to this political transformation, his spiritual quest led him from questioning Christian dogma to a deep, personal study of the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. This three-decade pilgrimage culminated in his magnum opus, Satyakama, and his formal conversion to Hinduism in 1932, when he adopted the name Satyanand meaning 'one whose joy is in Truth', as the final, honest expression of his evolved beliefs and as a practical necessity for his family's full integration into their adopted community.

His formal conversion to Hinduism in a simple ceremony in 1932 was, therefore, not a sudden decision but the final, culmination of his quest. In his letter to the editor of Harijan, he explained:

Each of us who takes spiritual matters seriously finds in the course of time the path wherein his spiritual aspirations and needs find their truest satisfaction. It was because I found mine in the spiritual outlook of the Upanishads and the Gita more completely than anywhere else that I wished to be a member of the Hindu community and thus afford those I loved the opportunity to develop freely and naturally in the midst of the atmosphere that had these great scriptures as their basis.

Maximiani Portaz to Savitri Devi

In stark contrast, if Satyanand Stokes's journey was one of discovery, Savitri Devi's was one of rigid, pre-formed ideological confirmation. She arrived in India not on a spiritual quest, but on a political mission to find a "living pagan Aryan culture" that could validate her fervent, pre-existing Nazi beliefs.

Her engagement with Hinduism reveals a temporary and superficial tempering of her racism for purely pragmatic ends.

In her early work, A Warning to the Hindus (1939), she advocated for a tactical relaxation of caste prejudice, arguing it was a necessary sacrifice for the "self-preservation" of the Hindu elite to create a unified political front against religious conversions. This was not a change of heart but a cold calculation.

Over time, even this pragmatic flexibility vanished, and her core racism resurfaced, now cloaked in Hindu terminology. She began to champion the caste system as a divinely ordained racial hierarchy, an "ideal racial caste system", designed to preserve Aryan purity, thereby fully fusing her esoteric Nazism with a hateful and distorted interpretation of Hinduism.

This final, hardened ideology reveals her entire project not as an interpretation of Hinduism, but as an act of ideological conquest. She weaponised the Bhagavad Gita to serve this end, seizing upon Arjuna's fear of varna-sankara (confusion of castes) and twisting it into a biological condemnation of racial mixing.

Krishna's call to dharma was perverted into a justification for 'detached violence', chillingly equating the ideal Kshatriya warrior with the 'perfect SS warrior'.

Where Stokes remained a perpetual student, allowing the Gita to reshape his worldview, Savitri Devi was an ideological coloniser, forcing the scripture into the rigid mould of her pre-existing hatred. Her legacy, therefore, is not one of synthesis but of violent appropriation, a testament to how sacred texts can be twisted to sanctify a politics of absolute hatred.

Curiously, Stokes, a strong devotee of Bhagavad Gita also saw the possibility of this appropriation attempt and wrote to Congress high command, warning of this as a global danger. He wrote to Gandhi thus:

A new caste system, based on race and power, would become firmly established with the German “Aryan” as Brahman and Kshatriya, the other European races as Vaishya, and the non-European peoples as the Shudras of the world.

So he wanted Gandhiji to see Ahimsa in a holistic manner and support the defeat of Hitler. Incidentally, Sri Aurobindo, as early as 1940 had perceived the demonic nature of Nazi movement and its corrupt pagan nature. He wrote a poem 'The Children of Wotan'.

...A seed of blood on the soil, a flower of blood in the skies.

We march to make of earth a hell and call it heaven.

The heart of mankind we have smitten with the whip of the sorrows seven;

The Mother of God lies bleeding in our black and gold sunrise...

Mahatma Gandhi initially considered Nazism as just another violent Western political philosophy. Many Indian nationalists were taken by the idea of a possible Nazi support for Indian freedom movement given the use of words like 'Aryan' and the use of Swastika.

With Whom Does Real Hindutva Align?

This reveals the unbridgeable chasm between Maximiani Devi's racialist appropriation and the foundational principles of Hindutva thinkers like Veer Savarkar and Mahatma Gandhi. The distinction is best understood through the lens of Dharma.

For Devi, any relaxation of caste hierarchy was, at best, a temporary, tactical concession for political survival, an Aapad dharma. In stark contrast, Veer Savarkar called for the caste system's complete destruction, framing the eradication of untouchability not as a matter of convenience, but as an 'absolute Dharma' and a 'command of Dharma'.

On this moral imperative, Savarkar found common ground with his political adversary, Mahatma Gandhi, who also condemned untouchability as a profound

Thus, Savitri Devi's 'Hinduness' is a grotesque caricature, the projection of a foreign, supremacist ideology that contradicts the core anti-caste convictions of the very movement she claimed to admire. Its danger lies in its allure to those who mistakenly believe a rigid, birth-based hierarchy is an essential part of Sanatana Dharma, when for its key reformers, it was an evil to be uprooted.

Two Models and Contemporary Politics

The failure to distinguish between these two paths, between the civilisational coherence exemplified by Stokes and the exclusionary nativism embodied by 'Savitri' Portaz, is the fundamental error in any proposed alignment between Hindutva and the Western right-wing.

The universalism, spiritual egalitarianism, rejection of biological racism, birth-based social hierarchies and acceptance of pluralism inherent in the principle of Hindutva are philosophically incompatible with the exclusionary nativism, racial undertones, and authoritarian tendencies that characterise much of the Western right-wing.

Profound dangers and seductive fallacies arise when proponents of Hindutva seek alignment with the modern Western right-wing based on superficial similarities. While both movements may share a rhetoric of nationalism, cultural preservation, and a critique of wokeism and Islamist extremism, their foundational ideologies are not just different; they are, in many crucial respects, philosophically antithetical.

The Fallacy of Equating Civilisational Unity with Exclusionary Nativism

A core tenet of the contemporary Western right-wing, from European populist parties to the American alt-right, is nativism, an ideology asserting that a nation should be inhabited exclusively by a homogenous "native" group, and that non-native elements, whether people or ideas, are an existential threat to the nation-state. This is a fundamentally exclusionary, purist, and often xenophobic worldview.

The great fallacy arises when this is equated with the Hindutva concept of civilisational unity.

The Hindu civilisational model, as articulated by thinkers from Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore to Veer Savarkar and embodied in the principle of Samanvaya, is historically inclusive and synthetic. It describes a broad, assimilative civilisational process that has successfully integrated diverse peoples, Shakas, Jaths, Kushans, and others, into its socio-cultural fabric over millennia.

Its foundational Samanvaya process is a philosophical commitment to discovering unity in diversity, not by eliminating it.

This is the philosophical opposite of nativism.

The Hindu civilisational model has been a sponge, absorbing and integrating myriad influences; the Western right-wing model is a fortress, designed to repel and exclude.

An alignment with the latter forces Hindutva to abandon its unique pluralistic genius and adopt a narrow, alien framework of ethnic nationalism that is not only philosophically incompatible but practically unsuited to the profound and celebrated diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

The Fallacy of Conflating Cultural Identity with Racial Purity

Savitri Devi serves as the ultimate cautionary tale of this second, and perhaps most dangerous, fallacy. She interpreted Hindu concepts like 'Aryan' and 'caste' through the crude, biological lens of Nazi racial science, a fundamental and violent misreading of a complex socio-spiritual system.

Her entire ideology was predicated on the idea of a pure, biological race whose blood must be preserved at all costs.

This stands in stark and irreconcilable opposition to the views of foundational Hindutva thinkers. Veer Savarkar, the very man who popularised 'Hindutva', explicitly rejected biological racism and the notion of racial purity.

In a remarkable passage celebrating the reality of human admixture, he argued that 'sexual attraction has proved more powerful than all the commands of all the prophets put together' and that 'to try to prevent the commingling of blood is to build on sand'. He concluded,

Truly speaking all that anyone of us can claim... is that one has the blood of all mankind in one’s veins. The fundamental unity of man from pole to pole is true

This highlights the critical distinction between a cultural-civilisational identity (Sanskriti), which is central to Hindutva, and a biological-racial identity, which is often foundational to Western right-wing extremism.

The former is based on shared values, history, and philosophy and is potentially open to anyone who adopts them. The latter is based on blood and lineage and is inherently and permanently exclusionary.

To align with the Western right-wing is to risk importing a toxic racialist logic that is not only alien to Hindu thought but was explicitly and forcefully repudiated by the very seers who took forward Hindutva into the modern age.

The Fallacy of Equating Dharma with Authoritarian Theocracy

A third and profoundly dangerous fallacy is the conflation of the Indic concept of Dharma with the creedal dogmatism characteristic of Western right-wing religious fundamentalism.

Western religious fundamentalism is typically a creedal religion, deriving its authority from the belief in a singular, exclusive sacred text that is considered the 'only absolute truth'. Its political expression often involves the attempt to impose a rigid set of non-negotiable dogmas upon society, demanding a complete break with other traditions and viewing alternate spiritual paths as inherently false.

This approach is fundamentally exclusionary, seeking to enforce a singular, divinely revealed code and uniting its followers through a 'commonness of belief' rather than a shared culture.

This stands in stark and irreconcilable opposition to the concept of Dharma as understood within the authentic Hindu tradition. Hinduism is presented as the most perfect type of a 'non-creedal' religion, one that is not based on a singular, absolute truth but on a broad spirit of free research and experience.

Dharma, in this context, is not a rigid code from one book but a transcendent ethical and moral principle that stands above any single text or even the will of the majority.

Hindutva thinker Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya (1916-1968), posited Dharma, which he also referred to as Chiti, the national soul, as this transcendent guiding principle. To illustrate this, Upadhyaya used the historical example of Charles de Gaulle, who defied the will of the French majority when they voted to surrender to Hitler.

De Gaulle, Upadhyaya argued, derived his right to resist not from the popular will, but from the higher Dharma of national independence. This demonstrates a crucial difference. In the Hindutva framework, Dharma acts as a check on power, a set of eternal principles to which even rulers and majorities are accountable.

The crucial difference is functional:

Western fundamentalism seeks to use political power to impose its exclusive creed on society.

In the Hindutva framework, dharma acts as a check on power, providing a set of eternal principles to which even rulers are accountable.

To align with Western religious fundamentalism would force Hindutva to abandon its unique pluralistic heritage and its dynamic concept of Dharma in favour of a narrow, exclusionary, and dogmatic framework that is philosophically alien to its core.

The Long Term Alternative for the Current Crisis

Once the Hindutva distances itself from these three fallacies that make it align with the right-wing vision of the West, then one can see the path to navigate not only the current crisis but also set a protocol for sustained future economic policy.

International trade, investment, and diplomacy should be viewed not as weapons in a zero-sum contest for supremacy, but as tools for mutual benefit and global well-being. This approach does not preclude firm negotiations or the resolute protection of legitimate national interests, but it frames these necessary actions within a broader ethical context of global responsibility and a refusal to engage in purely transactional, ego-driven geopolitics.

Achieving this capacity needs two-pronged policy framework.

The nation's internal policy, its sva-dharma, is to its own people. This sacred duty is fulfilled by implementing the principles of Integral Humanism, building a self-reliant, equitable, and sustainable domestic economy through Swadeshi and Antyodaya.

This creates a strong, resilient foundation, ensuring that India's engagement with the world comes from a position of internal stability and justice, not desperation or weakness. From this position of internal strength, the nation's external policy should be one of principled cooperation for the welfare of the world (Loka-samgraha), in line with the timeless Indic value of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.

Atmanirbhar Bharat is an embodiment of this vision of holistic self-reliance.

Economic 'Karma Yoga'

The path forward lies in embracing the spirit of Economic 'Karmayoga', a vision rooted in the Gita's timeless wisdom and articulated through the indigenous framework of Integral Humanism. This is the path of a self-assured, self-reliant, and compassionate India.

It demonstrates the enduring relevance of the Gita's message: that right action, performed with wisdom and detachment, remains the surest path to both individual liberation and collective well-being in a complex and interconnected world.

This is the choice at the fork in the road. It is a choice for an authentic future not authoritarian falsehood, one that resists the siren song of foreign ideologies of blood and soil, exclusiveness and violence and places its faith in the enduring, universal, and harmonious spirit of India's own civilisation, the Sanatana Dharma.