Ideas

Thoughts On Diwali 2019: Partnering with Rama for the Common Good

Anantanand Rambachan

Oct 27, 2019, 04:26 AM | Updated 04:26 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

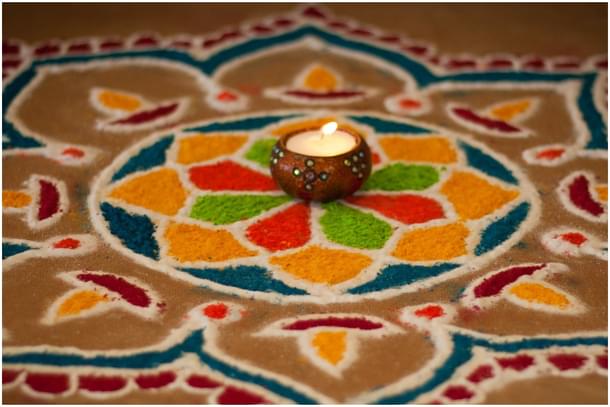

The word “Diwali” means an arrangement or a row of lights. Diwali is celebrated on the darkest night of the year when the necessity and the beauty of lights can be specially appreciated.

Given the rich regional and cultural diversity of India it should not surprise us that there are many narratives and traditions connected with Diwali.

One of the most popular traditions associated with Diwali is taken from the Ramayana, one of Hinduism’s sacred texts that tells the life story of Rama.

‘Ramayana’ literally means, ‘Rama’s journey.’

Diwali celebrates the return of Rama to his home in north-India city of Ayodhya after an exile of 14 years and his overcoming of the tyrannical, Ravana.

Rama was forced into exile by his stepmother who wanted her own son, Bharata, to occupy the throne of Ayodhya. Citizens of Ayodhya joyfully welcomed Rama home by lighting thousands of earthen lamps on the streets and in their homes.

For Hindus across our world, the story of Rama is more than the exile of a prince, his experiences in the forest, and his eventual return home. Rama is venerated as a divine being, the embodiment of God.

It is this belief that keeps the story and traditions of Rama alive, ensures its transmission across the ages, and generates new commentaries on the Ramayana. The story of his life is read as revealing something of the nature of God and God’s relationship to us.

My reflection is based on reading of the Ramayana as a theological narrative that instructs us about the divine in our world.

In spite of the belief that Rama is the divine in human form, there is a consistent feature of his mode of acting in the world to which the Ramayana calls our attention.

Rama continuously seeks human help to accomplish his purposes, small or great. In fact, we may say that Rama’s life is a story of such partnerships. These examples fill the pages of the Ramayana.

He needs the help of a boatman to ferry him across the Ganges river.

He asks the advice of the forest dweller, Valmiki, when he wants to find a suitable place to build a hut.

He befriends Sugriva and requests him to lead the search to find Sita who is kidnapped by Ravana.

He chooses Hanuman as a messenger to convey his words of love to Sita in her sorrow.

He requires help to build a bridge to Ravana’s fortress in Lanka and, to defeat Ravana, the greatest of his challenges, Rama assembles a large army, drawn from the entire creation.

At the end of the struggle with Ravana, he sends Hanuman as an emissary to ascertain if his brother Bharata and the citizens of Ayodha want him back. He returns to the lights of Diwali only when he is assured that the city loves him.

The point of all these examples in the Ramayana cannot be missed. God’s purposes are accomplished through partnership with human beings. God seeks the active cooperation of human beings.

The Bhagavadgita, another one of our sacred texts describes the divine, in the thirteenth chapter (14) as having hands everywhere, feet everywhere, eyes, heads, faces, and ears everywhere.

sarvataḥ pāṇi-pādaḿ tat

sarvato ’kṣi-śiro-mukham

sarvataḥ śrutimal loke

sarvam āvṛtya tiṣṭhati

Although a verse like this is read often as speaking of divine omniscience and omnipotence, it is faithful to the Hindu tradition to read such a text as teaching that our hands, legs, eyes, heads and ears are the instruments for the work of the divine in our world. The verse repeats the word ‘everywhere (sarvataḥ)’ to emphasize all hands.

God’s hands are not just Hindu hands, Christian hands, Muslim hands, Jewish hands, Buddhist hands or the hands of those with no religious commitments. God’s hands are black hands, brown hands and white hands. No hands are excluded; all hands are God’s hands.

To speak of all hands as God’s hands is not to undermine human agency or to imply that human beings have no choice. The divine does not violate human freedom through the exercise of force and power. Rama does not protest his exile and he returns to Ayodhya on the night of Diwali only when he knows that he will be welcomed back.

Partnering with God and becoming God’s instrument is a privilege offered to us by God and a choice that we must make. It is a choice of love which is by nature gentle, non-coercive and the very antithesis of compulsion.

We are free, like Ravana in the Ramayana, to reject partnership with the divine and to take an adversarial stand or like Hanuman to align ourselves in love and for love with divine purpose.

What does it mean to partner with God?

What does it mean, as the Bhagavadgita describes, to be God’s hands and feet, God’s eyes and ears?

The end of the story of the Ramayana is not the defeat of Ravana, but the return of Rama to Ayodhya and the establishment of a new community. The Ramayana speaks of this community as Ramarajya or the kingdom of God.

Ramarajya is not a Hindu community. If the hands of God are all hands, the community of God is an inclusive one that includes and cares for all being. It is a community free from poverty, disease and illiteracy. Hate and violence are overcome and human beings devote themselves in love to serving each other. Nature flourishes in radiant abundance.

If the formation of an inclusive community of love, justice and the overcoming of suffering is the ultimate purpose of the divine in the world, we become partners with God when we engage in work to overcome suffering rooted in poverty, illiteracy, disease hate and violence.

We become God’s hands and feet when we work positively to build inclusive communities of love, justice and peace, where the dignity and equal worth of every human being is affirmed.

The example of Rama teaches us that such a community does not come into being miraculously through divine intervention. It requires our active cooperation as co-creators every step of the way.

Without our partnership, the birth of this community is not assured. This fact is a profound human responsibility, but also one that acknowledges our human freedom.

Diwali reminds us of God’s invitation to become active and responsible partners for the universal common good and of our freedom to accept or reject this divine call. We must choose.

Diwali blessings to each one of you and your families.

Anantanand Rambachan is Professor of Religion at Saint Olaf College in Minnesota, USA and Co-President, Religions for Peace. His most recent book is ‘Essays in Hindu Theology’.