Ideas

Why The New Motor Vehicles Act Could Become A Blockbuster Success

Sarthak Agrawal

Sep 16, 2019, 02:48 PM | Updated 02:48 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The latest amendments to the Motor Vehicles Act are attracting a lot of public attention, especially since the new law came into effect on 1 September. Fines for many traffic violations have been increased by 10 times or more; for instance, driving without a licence which attracted a penalty of Rs 500 until last month will now require shelling out Rs 5,000.

Broadly speaking, there have been three kinds of responses to this move. There is a section of people who see it as a game-changer that would make our roads safer and transform commuters into law-abiding citizens due to fear of stiff penalties. The other group laments that the new rules will increase corruption and do little to improve road safety.

Finally, some people have complained that the fines are too high for the average Indian that must be reduced, and given the state of our roads, blatantly unjust.

The third argument is most peculiar since it seems to be a criticism of some compulsory road tax levied by the government. These fines are easily avoided by following the law and are meant to save lives and enforce discipline — not reward the government for building excellent infrastructure.

As for the first couple of points, I show using simple economic analysis why this law might be very successful in reducing road accidents, aided by the corruption inherent in our policing system. If the law was followed judiciously and corruption entirely absent, the fear of stiff penalties would surely improve behaviour on roads.

However, even in a system like ours, the new rules will go a long way in achieving their objectives — and may I add here, perhaps more effectively.

At the outset, we must first ask the question: why do so many people flout traffic rules?

This is a puzzle because abiding traffic law in most cases is very easy — wearing a seatbelt, purchasing a helmet, or getting a pollution under control (PUC) certificate, and all cost between nothing and a few hundred rupees.

In all but a few cases, rectifying behaviour has very little cost, especially so when considered alongside the fines non-compliance attracts (both earlier and more so now).

Why then is the law not taken seriously? It could be a combination of three things: the effective fine faced by commuters is much lower due to bribery, the probability of being caught is virtually zero, or people are simply following the crowd.

Given this context, we now ask what effect will a steep rise in fine amounts have on commuters? In my opinion, there are likely to be two main changes.

Firstly, the average bribe in the market will also rise multiple times. If the bargaining between an offender and a policeman breaks down, both of them know that the errant driver will now have to pay a much higher fine. The latter exploits this knowledge and is perhaps successful even in obtaining a 10 times rise in his bribe.

Secondly, we can expect more monitoring and enforcement from traffic policemen in the new regime.

Interestingly, many cops will act in this manner even without any such directive from their bosses. This is so because the cost-benefit calculation inherent in the decision to patrol will shift in favour of greater patrolling since while the costs remain unchanged, the benefits of catching an offender increase because of higher prospective earnings in bribes.

When evaluating whether to take a tea break at 4 pm in the day, knowing that the pleasure of sipping a cup of hot chai will now cost more than 10 times as much (in foregone earnings), more policemen might be compelled to be on duty.

The impact of these changes is best understood in a diagram below.

On the vertical axis we have the amount of patrolling while the horizontal axis measures the number of offenders on the road. The downward sloping line (light red) captures the idea that when frequency of monitoring increases, more people obey the law.

On the other hand, policemen patrol more often when there are a greater number of offenders around since their expected income from bribes goes up.

The other line (light yellow), therefore, slopes upwards. Where the two intersect, we obtain the actual level of monitoring and the number of offenders. When fines increase, the number of offenders for a given level of monitoring goes down since getting caught costs a lot more.

At the same time, for a certain number of offenders on the road, policemen will monitor more since their rewards from catching a lawbreaker increase drastically.

In short, the possibility of a bigger bribe acts as a better performance incentive. As we see below, these dynamics will eventually lead to a steep fall in number of offenders.

Compare this with a situation where bribery is completely absent. The level of monitoring is independent of the number of offenders and is perhaps quite low, as depicted by the horizontal line in figure 2.

We might have a situation where in a system with zero corruption, and without a 100 per cent role for technology, the number of offenders is still higher than the current system since there is little incentive for cops to do their jobs well. I am not hailing the pervasive corruption in our society as some kind of a virtue.

However, in this particular context, it is efficiently substituting for a missing institution — performance incentive for poorly paid and supervised public employees — and helping drive results.

There is a genuine concern amongst some people that amidst all this, hyperactive traffic policemen might overstep their mandate and start harassing law-abiding commuters.

However, under the new regime, cops are being asked to wear body cameras and submit video evidence if the case goes to court. If a person on the receiving end is convinced she has followed the law, she would insist for a challan and refuse to pay a bribe (more so now since bribes will be steeper too).

Even on the cop’s side, the value of his time is now much higher and he would rather direct his attention to an actual defaulter as opposed to making up a case where none exists.

Nevertheless, it is imperative that for individuals, who wish to appeal their challans, the judicial process is made more friendly and video evidence carefully considered in the court.

Interestingly, as the number of offenders on the road decreases, overall earnings of policemen from corruption might decline too. What is most ironic is that this will be an aggregate outcome of their individual actions.

If the policemen do not demand significantly higher bribes under the new regime, nor do they patrol more frequently, behavioural change will be hard to come by and the number of offenders is unlikely to dwindle significantly.

Due to the herd instincts wired in our brains, once a critical number of people on the road start observing the law, rest will follow. One of the reasons for high non-compliance is that the opposite seems to be the case at present.

If the mechanism discussed above is successful in pulling a large number of people to the right side of the law, we might see a social norm quickly developing which nudges even errant (or new) drivers to mend their ways.

Once the norm is in place, it might not even be necessary to increase challans proportionately in future with rising incomes and inflation.

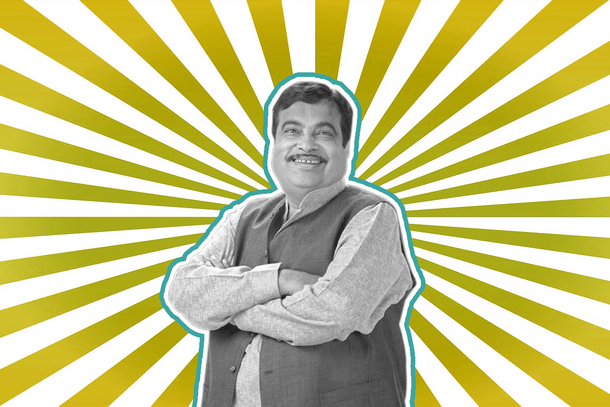

Some states are considering reducing fines by exercising their discretionary power since this issue lies within the concurrent list of the Indian Constitution. The Union minister concerned is not amused; a visibly irritated Nitin Gadkari said the burden of saving lives does not solely rest on his shoulders and the law was enacted not for filling state coffers but only with the intention of enforcing discipline.

He is absolutely correct; this law will improve road safety, challenge existing norms, and eventually even reduce corruption on the road. Better sense must prevail, if for nothing else, but to save innocent lives.

Sarthak Agrawal has a BA (Hons.) in Economics from Shri Ram College of Commerce and an MPhil in Economics from the University of Oxford.