Ideas

World Watches, Wide-Eyed, India’s Gusto In Tapping Its Gust-Power

Swati Kamal

Oct 30, 2018, 02:55 PM | Updated 02:55 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Last week, an Indian organisation received the top UN Investment Promotion Award at a United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) event in Geneva, for its efforts to boost investments in the renewable energy sector. Invest India, the non-profit venture of the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, was given this award as recognition for “servicing and supporting a major global wind turbines company in the establishment of a blade manufacturing plant in India, while committing to train local staff and produce 1 gigawatt (GW) of renewable energy (RE). Implementation of the project is expected to reduce India's wind energy cost significantly".

In the Indian RE scenario, the spotlight is usually on the sun; wind energy initiatives, however, have been quietly making strong and steady strides, and standing tall in the face of challenges – much like the windmills that power it.

The RE sector as a whole has been growing. As per the latest government data, the share of energy from renewable energy sources has reached an all-time high of 13.4 per cent, as this article tells us.

Data from the period April 2015 shows an upward trend; the peaks and troughs that follow each other cyclically are due to the seasonality factors of sun and wind. The cyclical lows and highs keep getting higher, as we see, and both generation and share of RE in total energy has risen till August 2018.

To recap, the 2015 Union Budget had set forth a target of 175 GW RE installed capacity by 2022, of which 60 GW was to come from wind. By 2014, wind had an installed capacity of 21 GW already, while solar installed capacity was 2.6 GW. In that sense, wind needed a lower rate of growth to reach 60 GW.

Yet, much action has happened on wind power initiatives. As of June this year, the total installed capacity was 34.293 GW, which puts it at number four in the world, after China, US and Germany.

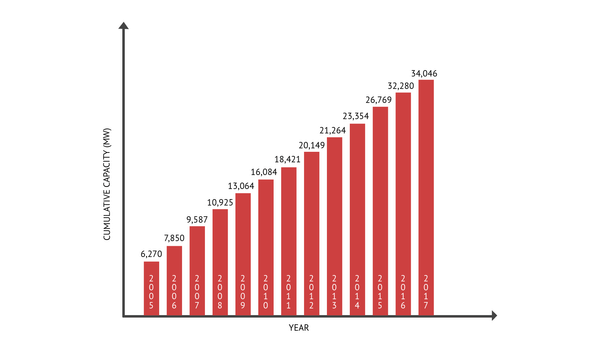

Installed wind power capacity

Capacity additions over the years have risen, and we see that post 2014, the gains have accelerated on the back of the aggressive targets set by the government. Read how the industry has been moving steadily ahead, and also how optimism fills the air, going forward: Whereas earlier, annual installations rarely exceeded 3 GW – the highest so far being 5.5 GW in 2016-17 – now we’re talking 9 GW-worth bids having been completed this year, and another 8 GW could be bid out before March. The order book in 2019-20 could start 16 GW, at least half of which could be executed during the year.

If capacity is growing, so are technical advances. Renewable energy major, Suzlon, commissioned the country’s tallest hybrid concrete tubular wind turbine generator in Tirunelveli district earlier this month. Suzlon put up one of its machines on a 140-metre high tower, the lower part of which was built with concrete, leaving scope to increase the height. Taller towers mean longer blades which, in turn, means larger swept areas, leading on to better capacity utilisation and, hence, more energy. Suzlon has over 11.9-GW wind power installed, and believes that the competitive bidding process has led to evolution in the market, making it essential to innovate and invest in research and development in order to lower cost of energy.

October also saw Denmark willing to open a Danish-Indian research centre for the development of wind energy in India, as reported by Copenhagen Post. Broadly, this is a three-year strategic sector co-operation with Indian ministries and national institutes, the focus being wind energy and the integration of renewable energy into India’s electricity network. Denmark is upbeat about the potential of the partnership, as India “is expected to become one of the world’s largest renewable energy markets in the upcoming years with wind energy being its leading interest.”

The Denmark development is significant – it is a pioneer in commercial wind power since the 1970s, and Danish companies also command a large share of wind turbine manufacturing. The article appeared to bordering on being awestruck: “If India can follow through with its plan, it will have a capacity to produce 66 gigawatts of wind energy in four years – Denmark currently has a capacity of 4.5 gigawatts. Furthermore, India is planning on gaining another 30 GW from offshore wind parks by 2030. This amount of power corresponds to 23 times the capacity of the 1.3 GW plants built in Denmark since 1991. “Indeed, all of the world is watching India’s gusto in making full use of its gust-power!

Ministry of New and Renewable Energy’s had in April 2018 invited expressions of interest for its offshore wind farms from developers to set up a 1 GW offshore wind farm in the Gulf of Khambhat, off the Gujarat coast. Several domestic and international companies had responded. The target for wind power capacity was set at 5 GW by 2022 and 30 GW by 2030. In October 2015, government had released the National Offshore Wind Energy Policy; in March 2018, it was exploring the potential of setting up a government-owned offshore wind farm off the Tamil Nadu coast, with four to five windmills of 6 MW capacity, each.

Offshore wind farms are windmills installed on the seabed, rather than on land. They generate higher amounts of power, because of the larger wind turbines, and also have minimal space constraints and physical obstructions. However, costs are high with power generation costing five times the tariffs for onshore wind power, even though the experience across the world shows lowering of offshore tariffs over the years. Europe, China, Japan and the US are the countries that invest in offshore wind energy.

Of course, while these plans will put us in the same league as them, a little bit of pondering over this is required, given the hurricanes and typhoons that happen along India’s coastline. Even though the Arabian Sea is less disposed to these, Hurricane Ockhi in 2017 had landed exactly near Gulf of Khambhat, where the offshore wind farm is being planned currently. The area is also located in the seismic zone. Would an alternative location along the West Coast make more sense?

Powered By Government’s Ambition

It can safely be said that a large component of the optimism in this sector comes from the policymakers’ charge.

Even though low tariffs were the Industry’s own doing – bids of Rs 2.44 a kWhr in the third round, with some firming in the fifth round to Rs 2.77, but still much below levels during the fixed feed-in tariff regime. Industry players now point towards the dangerous consequences of low tariffs. This will lead to non-viability of projects in non-windy states, and loss of jobs for millions as vendors’ margins are pressurised by turbine manufacturers, they say.

Recently, the Indian Wind Turbine Manufacturers Association has put forward several demands related to sub-station wise auctions, Solar Energy Corporation of India selling the power procured from wind auctions only to DisComs in non-windy states, and assured volumes as detailed here.

The government has hand-held the industry through the years, and painstakingly removed thorns that hamper its working. Last year, for instance, was a difficult year for the industry. The government took a slew of measures to ensure ease of working for companies, including a) guidelines by the Power Ministry to prevent DisComs from directing ‘back downs’ (which means that they would unplug their transmission from the grid when it got overloaded), once the wind power plant was commissioned; b) the minimum power purchase agreement (PPA) would be 25 years and in the interim if any changes in laws caused losses to developers, they would be compensated by the power procurer; c) Evacuation of power if not done as per agreement would need to be compensated. Several other conditions were laid down and also the crucial ones related to auctions – both open and closed as also reverse auctions – for smooth functioning of the bidding process and supply of power.

Clearly, the government is doing all that is in its power. But should it? – is a different matter.

Lest This Ambition Be Quixotic

An interesting perspective related to this is provided in a Brookings report titled, ‘Working to turn ambition into reality. The politics and economics of India’s turn to renewable power’ by Rahul Tongia and Samantha Gross. This paper seeks to question further investments in RE, in the absence of accompanying institutional and regulatory actions to reduce the cost of grid integration.

The first challenge it talks about is costs - as of now, the cost of RE cannot yet compete against most existing coal-fired generation, despite bids as low as Rs 2.4 per kwh. It mentions that “a number of analysts and stakeholders have called the lowest bids not just aggressive, but bordering on irrational”. Whereas falling RE costs have inspired discussions of “grid parity”, when RE will push coal off the Indian grid, the fact is that the full costs of integrating RE into the grid have not been included in this. In a December 2017 report, the Central Electricity Authority had estimated the hidden cost of RE on the rest of the system at approximately Rs 1.5/kWh of RE for selected high-RE states.

Next is DisComs: almost all are owned and controlled by state governments and most are struggling financially - so that delayed payments, renegotiating PPAs, or avoiding signing new PPAs are definite possibilities.

The third point is about RE integration into the grid - as RE’s share increases, it will have to be integrated, and other sources like coal will need to back down to accommodate it. But the point is, that RE generation will be rising yet variable generation. RE is not dispatch-able nor coincides with peak demand. So, for optimum absorption, it will need a “long-distance RE-centric transmission”, which requires investments in this area. At high levels of RE penetration, the system requires storage solutions so that RE can provide power when it is needed, and we need a clear roadmap for that. The authors project the need for massive new storage capabilities - at acceptable costs - starting around early 2020s.

Additionally, RE potential, especially wind power is concentrated in a handful of states. RE output on some days will likely surpass total electricity demand in these states, even by 2022. Adding to the challenge, the frameworks for sharing power across state borders are not robust.

The central government’s RE ambition cannot be translated into reality because the Centre cannot set RE targets for states. Where RE is far ahead - nearly all states with RE targets above 10,000 MW have a strong wind component - the targets are being met. Yet, the overwhelming majority of RE, anticipated in a handful of RE-rich states, is unfair as they bear a disproportionate burden in terms of grid integration. As they are faced with surplus electricity supply, and no mechanisms to compensate them exist, many of these states in the south and the west have delayed signing new PPAs for RE. The burden and costs of RE are now borne almost entirely by the RE-rich states. Enforceable renewable purchase obligations (RPOs) are the way out, and they were tried by the central government, but met with resistance from states.

These existing challenges must be dealt with, if investments in RE are to yield reasonable benefits. Already, availability and cost of capital are huge impediments to RE development in India; billions of dollars are required in solar and wind each, with wind being higher.

Why RE at all then? The authors make an interesting and important point: that India does not need to meet its RE targets to achieve its goals under the Paris climate agreement. They argue that “the central government focuses on RE to show leadership in energy policy. Moreover, it sees RE policies as a way to attract global capital, which is not forthcoming for coal. RE developers are a natural ally in this vision”. The overall picture is confused, with mixed dispositions - the states lag the central government in RE ambitions, and do not have Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPO) that add up to the national targets; for consumers, RE targets don’t matter as long as they get cheap and reliable electricity; for railroad, RE is a menace as it earns its revenues from moving coal. And finally, there’s the political power of coal producers.

The authors conclude by saying that whereas the multitude of challenges described in their paper are not unique to India, and are inevitable in any large-scale transition; however, India’s timeframes are exceptionally aggressive and it is starting with a much weaker grid, so greater effort will be needed to plan for a high RE future.

In the light of all this, efforts must be taken to build `RE support system’. Global technologies, batteries and smart grids, experience and expertise and better financing can act as important supplements to India’s optimism in and enthusiasm for RE - and specially in wind energy, because it deserves it.

Swati Kamal is a columnist for Swarajya.