Legal

Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain’s Criticism Of Waqf Amendment Is Overzealous And Impractical — Here's Why

Monalisa Nanda

Mar 31, 2025, 01:52 PM | Updated 01:52 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The seminal Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2024, introduced in the Parliament in August 2024 has sent ripples across all quarters, be it social, political or legal.

Opinions on its merits and shortcomings have poured in from all sides. The Bill has met with a certain degree of resentment from those who believe that not enough has been done to dismantle the one-sided, minority appeasing character of the Waqf Act, 1995.

Among the most vocal critics advocating for more drastic changes is Advocate Vishnu Shankar Jain, whose recent 48-post thread on X proposes amendments that go far and wide beyond what the amendment presently does.

While reform is certainly needed, Jain's proposals represent an overcorrection that threatens to undermine the reformist and progressive approach that the Government has taken with the Bill.

Amongst other things, he has suggested for the dissolution of Waqf Tribunal and setting up the National Waqf Disputes Resolution Commission, for waqf surveys to be conducted by Waqf Boards instead of the State Government, etc — all the while drawing false parallels with the manner in which Hindu endowments and institutions are governed under law.

This stems from a stunted understanding of the issues surrounding governance of waqf while looking at it from a coloured, religious lens rather approaching it as a matter affecting land dealings.

The Government’s vision with respect to waqf governance, on the other hand, is thorough and comprehensive, and aims to dismantle the draconian, one-sided powers of the Waqf Boards, while ensuring that the vast number of properties categorised as waqf at the present do not fall into litigation upon the enactment of the amendment.

Why Waqf At Its Core Is A Revenue Issue And Not A Religious One

Undeniably, the origins of the existing Waqf Act, 1995 stem out of a hard political bargain reached by the PV Narasimha Rao-led Government with Muslim leaders in the aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

The government promised an arm and a leg to satiate the Muslim community by enacting a law that gave overarching powers to the State Waqf Boards to identify any property as waqf without any burden of proof, deeming evacuee properties left behind during partition to be waqf amongst other things.

However, the manner in which waqf governance has shaped up over the past three decades has taken it away from its original religious characteristics.

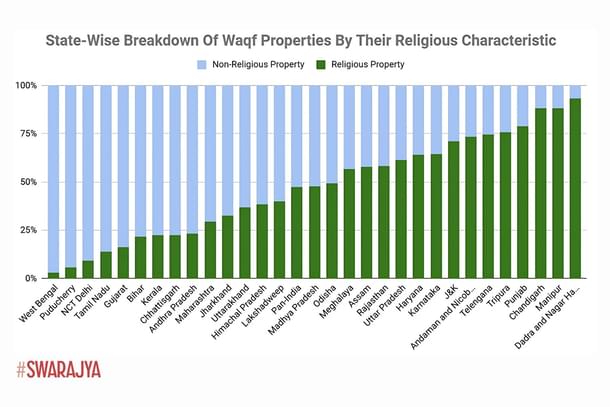

Out of the 8.7 lakh properties registered as waqf, nearly 52% are properties of non-religious character, i.e, agricultural land, shops, buildings, schools, etc. Furthermore, even out of the remaining 48% properties, nearly 40% are graveyards alone, and thus cannot be deemed to be active sites of practice of Islamic faith.

Thus, effectively, only around 30% of all properties categorised as waqf are actively religious in nature. This means, out of the 8.7 lakh properties classified as waqf, over 6 lakh properties do not see any religious practice and are merely encumbered pieces of land that cannot be transferred or converted, thus prohibiting their usage for any form of welfare or development either by the Government or by private parties. A state-wise breakdown of this is depicted in the graph below:

Thus, given that a vast chunk of waqf properties are non-religious, waqf governance is a matter that has immense ramifications on the manner of utilisation of land across the country as well as the value of real estate. Hence, viewing the issue from a religious perspective alone is inherently myopic. It is this historic wrong that the Government has set out to undo via the present amendment.

The Bill strives to bring extensive reforms by abolishing the power of the waqf board to identify any land to be waqf, requires for waqfs to be created by practicing Muslims only via a registered waqf deed, omits the provision for non-Muslims to mark their donations as waqf, gets rid of the provision classifying evacuee properties to be waqfs, provides for CAG audits of waqfs, etc.

These provisions, once implemented, will free up an extensive number of properties that are presently encumbered as a result of being classified as waqf.

It is this premise to the amendment that Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain has missed out in his vision for waqf governance in India. Beyond this foundational divergence of views, his propositions also lack substantive legal or logical backing.

On the matter of Waqf-related disputes

What Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain has proposed: He recommends that the Waqf Tribunal be disbanded and be replaced by a National Waqf Disputes Resolution Commission. As per his proposal, all the pending disputes before the Waqf Tribunal are also to be transferred to this Commission.

Why this proposal is superfluous: The proposal only replaces an existing quasi-judicial body with another quasi-judicial body with a mere name change.

Under the existing framework, it isn’t the Waqf Tribunal that is particularly problematic, it is the restrictive dispute resolution provisions that are a much bigger hurdle. For instance, the existing Act prohibits the Tribunal’s orders from being challenged before any Court.

However, this issue has already been resolved in the amendment Bill wherein the Tribunals’ orders have been made appealable before the respective High Court within a period of ninety days from the date of delivery of the order.

Furthermore, at present, nearly 41,000 cases are pending before the Waqf Tribunal. Replacing the Waqf Tribunal with a Commission only transfers this pile of pending cases to the Commission without resolving the pendency issue in finality.

On the matter of survey of Waqf properties

What Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain has proposed: That the State Waqf Boards bear the cost of survey of waqfs properties in the state instead of the State Government. His rationale behind this is for taxpayers' money not to be used in surveying waqf.

Why this proposal is superfluous: The Supreme Court, in 2022, had observed that Waqf Boards are “State” under the definition of Article 12 of the Constitution. This means Waqf Boards are a State Government authority.

Thus, there is no substantive difference between waqf surveys being conducted by either the Waqf Board or the State Government. In both the cases, costs are borne by the state exchequer as is the case for any Government survey conducted for the updation of land revenue records.

Moreover, given that the amendment Bill anyway gets rid of Section 40 of the existing Act that allowed for the Waqf Board to identify waqf properties and now waqfs can only be created via a registered waqf deed, the need for conducting waqf surveys becomes moot.

Additionally, the Bill also provides for the details of waqf properties for every state to be uploaded on a unified central portal within six months of commencement of the Bill, again negating the need for a survey.

On the matter of District Administration implementing Waqf Board directions

What Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain has proposed: He has argued that it is derogatory for the District Administration to implement the directions of the Waqf Board and has further stated that the managers of Hindu trusts are not put on a higher pedestal than the District Administration.

Why this argument is superfluous: As stated above, State Waqf Boards have been recognised to be a facet of the State Government itself. Thus, there exists no procedural or legal flaw in making the District Administration implement the directions of the Waqf Board.

Furthermore, this argument arises from a false parallel drawn between the managers of Hindu trusts and the Waqf Boards. In the context of Waqf, the equivalent of a manager of a trust would be the Mutawali or the caretaker of the Waqf and not the Board itself.

On the other hand, Hindu endowments are generally governed by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment Department of the respective state, as is the case in Tamil Nadu, for instance. Thus, in the Hindu context too, the Department of Endowments would naturally depend on the District Administration for implementation of their directions, given that the administration is responsible for the implementation of all executive actions in the district. Thus, this comparison is misplaced.

All or Nothing approach cannot be taken with Waqf reforms

To reject the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2024, is, in essence, to reject the larger vision of the Government of taking down the arbitrary and draconian power structures associated with the Waqf Act, 1995.

What Adv. Vishnu Shankar Jain has done by calling out the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC)on Waqf — for not incorporating the propositions made by him — follows the same line of thought as those who criticise the Government for not abolishing Waqf altogether.

A common thread that links these two perspectives is that they throw the baby out with the bathwater. While being deeply suspicious and critical of the amendment Bill, they ignore the vast and pervasive reforms that the Government has tried to introduce to the manner of governance of waqf in the country.

Note: The author would like to thank Ananth Krishna S for their inputs.

Monalisa Nanda is a lawyer and public policy consultant.