Magazine

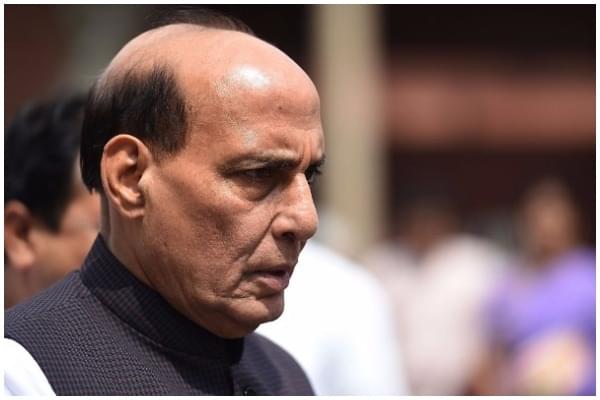

Book Excerpt: What Was Rajnath Singh’s Biggest Challenge When He Became Education Minister Of UP In 1991?

Gautam Chintamani

Nov 01, 2019, 02:02 PM | Updated Nov 16, 2019, 04:14 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Raajneeti: A Biography of Rajnath Singh. Gautam Chintamani. Ebury Press. Rs 290.56. (Kindle Edition).

The messy situation left behind by Mulayam Singh Yadav’s regime, one that was marked by turbulence and a stalled administration, might have helped the Kalyan Singh-led government come to power, but in just a few days after assuming office, Singh made it more than evident that he meant business.

Kalyan Singh established himself as a tough and able administrator with a no-nonsense approach in hardly any time and this became his signature.

There were instances when he jailed criminals, including MLAs, and also fired a minister from his own cabinet for violating his orders.

He went on to be known for not only the hard stance he personally took, but also of some of the members in his ministry, and the one who stood out was Rajnath Singh.

Singh was given charge of education of a state, which according to experts, had been deeply affected by political considerations and where the education system had become too politicised.

Uttar Pradesh was one of the few states in India that still had a Legislative Council — the upper chamber of the state legislature, a body in which teachers had guaranteed representation.

Teachers had traditionally been held in great regard in Indian society and, perhaps, that could be the reason why they were also given a special legal status by the Constitution of India which provided for representation to teachers and members who are elected by teachers in the Upper House of the state legislature.

UP’s council of ministers since 1952 had always had a representation of teachers, barring once when, in 1967, Chandra Bhanu Gupta as chief minister formed his 13-member cabinet that lasted for 15 days.

The significance of education in the politics of Uttar Pradesh can be gauged from the fact that many chief ministers have been former teachers, beginning with Sampurnanand, Sucheta Kripalani, Tribhuvan Narayan Singh, Mulayam Singh Yadav and Kalyan Singh.

Rajnath Singh too had joined a long list of education ministers in the state who had been teachers in the past, for instance, Acharya Jugul Kishore, Kalicharan and Swaroop Kumari Bakshi.

During Rajnath Singh’s stint as education minister, teachers wielded considerable influence both within and outside the state legislature.

There were other problems plaguing the education system that needed immediate attention.

Even after four decades of freedom from the British and despite an increase in the number of institutions, the education system in India had little to show in terms of achievements as well as what was being taught in schools.

The Kalyan Singh government gave more powers to management committees of private-aided schools, initiated self-financing courses and allowed self-financing schools besides transferring the power of pay disbursement to private managements.

In addition to wide-ranging alterations in lessons taught at the secondary-school level, including the introduction of Vedic mathematics and the addition of a chapter detailing the contributions of Keshavrao Hedgewar, the founder of the RSS, the teaching community took exception to many of Rajnath Singh’s reforms.

The introduction of Vedic maths raised many an eyebrow despite the fact that the world over, mathematicians found it helpful for children at pre-primary and primary levels to calculate complex numbers in a shorter time frame and sculpt young minds.

Questions were also raised about teaching children about the RSS even though historically, the RSS had not only been a part of mainstream nation-building activities but had also been invited to participate in the Republic Day parade in 1963 by then prime minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

At the same time, the teachers under the Madhyamik Shikshak Sangh (MSS), the strongest teachers union in Uttar Pradesh, were up in arms too.

The education minister’s ‘anti-teacher’ measures did not go down well and they announced a call for a boycott of examinations.

Things came under control only after assurances from the state government that there was no move to change legislation regarding the transfer of secondary teachers from one district to another or empowering the authorities to prolong indefinitely the suspension of any teacher.

If the field of education had become a springboard for successful politicians and a fecund garden for political activism, it had also spawned an industry with cheating in examinations as its mainstay.

In 1992, Rajnath Singh presented the historic anti-cheating law that declared cheating in examinations a cognisable offence.

The Anti-Copying Act, 1992, promised changes aimed at clearing the system like never before, whereby students caught cheating could be jailed.

This was accompanied by the simultaneous deployment of police in all examination centres across the state and its effect was more than palpable.

The percentage of students clearing the UP board high school exam came down from 57 in 1991 to under 15 in 1992.

Singh was told in no uncertain terms that his action would have far-reaching implications, or, in other words, his political future was at stake.

Even at the time of framing and, later, tabling the Act, there were well-wishers who sprung to advise the first-time minister.

Some of them went to the extent of hinting that the CM could probably try to fire from his shoulder and the credit, if it worked, would be Kalyan Singh’s while all the brickbats, the more likely outcome, would come his way.

But Rajnath Singh had no doubt about the measure. As a teacher, he had often found students not being inspired enough to do the right thing and the only way to bring about a change in the manner the young approached not just studies, but life, in general, would only be possible if they assumed greater responsibility, and what better place to start but one’s own self.

Gautam Chintamani is the author of ‘Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna’ (2014) and ‘Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak- The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema’ (2016)