Magazine

‘Mr And Mrs Jinnah’: A Tale Of Unrequited Love And Its Aftermath

Sanjeev Ahluwalia

Aug 08, 2017, 02:08 PM | Updated 02:08 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

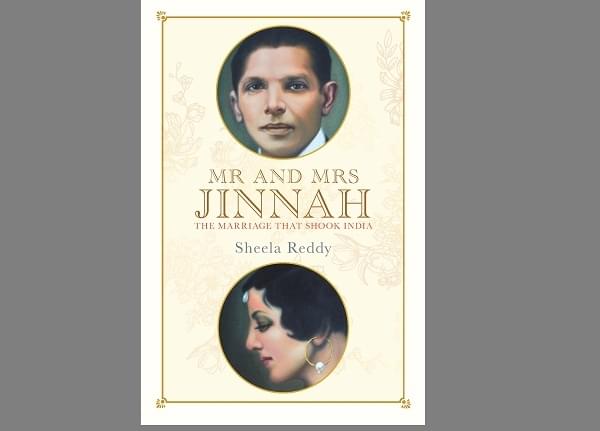

Reddy, Sheela. Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage that Shook India Penguin Random House India, 2017. 464 pp.

Sheela Reddy has a winner in this deftly crafted and diligently researched work on the life and times of Rattanbai Petit Jinnah. But this is not a racy read to be completed on the flight from Mumbai to Delhi. Try it only when you have the time and mindspace for it. There have been other works on the Jinnahs earlier – Khawaja Razi Haider’s Ruttie and Jinnah and Kanji Dwarkadas’s Ruttie Jinnah: The Story of a Great Friendship.

The recent release of the private papers of Padmaja Naidu provided the impetus to revisit Ruttie and her times. The author paints a broad canvas of the life and times of the commercial, professional, political and zamindari elite of the British Raj during the first three decades of the 20th century with the rumblings of guided democracy as a backdrop to profile Ruttie.

Other characters enter through the door opened by her, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah, or “J” as Ruttie called him – a relentless achiever, penniless son of a bankrupt Shia businessman in Karachi, who became the most sought-after barrister in Bombay, a multi-millionaire by the time he was 40 years old; the political leader of Indian Muslims and eventually, Quaid-e-Azam of Pakistan; austere to the point of having cold baths in freezing England and yet a dandy dresser, with an eye for fast cars and a mansion on Mount Pleasant Road, Malabar Hill.

Ruttie could have passed into the pages of history unnoticed had it not been for two red lines she crossed. First, at a time when caste and religion were impregnable walls for getting married, Ruttie, a Parsi, married Jinnah, a Shia, without her parents’ approval. Even today “Love Jihad” – a Muslim man marrying a non-Muslim woman, remains socially somewhat unacceptable. But in 1918, this was unheard of. Such were the religious rigidities, that even Motilal Nehru, a contemporary, anglicised Kashmiri Pandit barrister from Allahabad, twice president of the Congress, could not stomach his daughter, Nans (later Vijay Laxmi Pandit), marrying a Muslim man she loved. He successfully moved heaven and earth to break up the romance, aided and abetted by Mahatma Gandhi.

For Ruttie, to have followed her heart, without considering the consequences, was typically foolhardy but also exceptionally courageous. Second, characteristically, it was Ruttie who pursued and wooed Jinnah, a regular guest at the Petit mansion, which with its fabulous cuisine and gracious hospitality was a melting pot of high society.

“I abducted him” was Ruttie’s conclusive declaration to the judge hearing the abduction charge lodged by her father against Jinnah, once he came to know of their secret marriage according to Islamic rituals. It is easy to understand why Ruttie desired Jinnah. He was quite simply the most desirable man around, seemingly impervious to the charms of dozens of swooning society damsels, including, rumour has it, Sarojini Naidu. It was a challenge Ruttie could not ignore.

Not so obvious is why Jinnah wanted Ruttie. Salacious rumour, implausibly, insinuated that it was Ruttie’s wealth which attracted Jinnah. The author perceptively suggests that behind his mask of male invincibility lay an insecure man, craving love and affection. Ruttie, a romantic with undentable self-confidence, bravado and panache must have been the perfect blend of strength and womanly caring which Jinnah had never experienced. Their romance was short lived. From the time they got married in 1918 – when Ruttie turned 16, the cold embrace of Jinnah’s austere life began to cool the flames. It was not the age difference which mattered (Jinnah was 24 years older than her).

Jinnah had devoted himself to his work and to politics since 1898 when he first came to Bombay from Karachi. There was never any time for anything outside his professional and political ambitions. For Ruttie, life was meant to be enjoyed, travelling, meeting and making friends, partying and dancing – which Jinnah detested, interspersed with a fierce commitment to social causes and extravagant gestures defying convention, like sitting on Jinnah’s desk with her legs dangling, during business meetings.

The need to shock, to be out of the ordinary, manifested itself in unorthodox behaviour in Ruttie – refusing to courtesy to the Viceroy, instead greeting him with folded hands in the Indian way; venturing out into the Lower Bazaar in Shimla to eat chaat by the roadside, which upper class women of her time never did. Her portrait penned by Lady Reading, the wife of another Viceroy, is tellingly pointed: “Very pretty, a complete minx. She had less on in the daytime than anyone I have ever seen.” Not surprisingly, the marriage quietly unraveled.

Ruttie longed to join Jinnah in his struggle against the British. On one occasion, whilst Jinnah and the Home Rule Leaguers were engaged in a fierce struggle within the Bombay Town Hall to outvote the supporters of Governor Lord Willingdon, who wanted a memorial erected to honour the governor’s services, Ruttie succumbed to her secret desire to directly engage with the massive crowd gathered outside. Climbing atop a soap box, she delivered a rousing speech which had the crowd begging for more.

Such was the tumult they created, that the Commissioner of Police arrived to disperse the crowd. She refused to leave and resolutely stood up to the water cannons which were unleashed on her and the crowd, drenching them completely. Her beauty, now clingingly displayed, her passion and her determination were much praised.

Jinnah never commented on her actions. But Ruttie understood that her place was not to lead but to sit mutely behind Jinnah in public support of him. This continues to be the role for many talented but unfortunate Indian women even today in our patriarchal, gender-biased society. Jinnah was entirely self-centred, craving attention and love, but only on his terms and at his bidding.

The more traditional amongst modern Indian women continue to resignedly cater to it. But Ruttie never was a traditional Indian woman. She, more than any other, was what rich, Indian women from anglicised homes were being taught to become by imbibing the “enlightened” European-style education and lifestyle they were exposed to. That hers was the right way was reinforced by the examples of liberated womanhood around Ruttie. Sarojini Naidu, her key confidante and a frequent guest at the Petit Mansion, equally at ease in Gandhiji’s ashram as in Bombay high society, spent more time out of home on lecture circuits and Congress meetings than with her family in Hyderabad. But her good fortune was to find in MG Naidu the perfect, enlightened, supportive husband, gently explaining to their daughter, Padmaja, that her mother had committed to serve the nation, which thereafter became a duty she could not ignore even at the expense of spending less time with the family.

A girl child was born to the Jinnahs in 1919, known today as Dina Wadia married to Neville Wadia of the illustrious Mumbai industrial family. But parenthood created no new bonds. Like the other super rich, anglicised Indians of the time, the Jinnahs outsourced care of their child to European nannies and tutors. Jinnah took no interest in her, beyond willingly paying the bills of the nannies. But that was not atypical for the times.

Why Ruttie, who seemingly adored children and lived with a menagerie of pets, took no interest in her child, remains less clear, except if examined through the lens of Ruttie’s all-consuming love for Jinnah, which left no place for any other.

Seeking a stabilising routine, Ruttie emulated her mother and diverted her creative energies into wifely duties, turning Jinnah’s mansion, South Court, into a breathtakingly beautiful home. But she was unable to cope with the loneliness of unrequited love. Jinnah was not given to expressing his emotions. On the contrary, his entire life had been a struggle to master them.

Ruttie, ostracised by the Parsi community, took refuge in dancing, the occult, Theosophy and ultimately drugs. Ironically, Motilal Nehru visited the lonely Ruttie whenever he was in Bombay. Every visit to the miserable Ruttie must have served to reassure him that he had done the right thing in saving his own daughter from crossing the communal divide. By 1928, the couple were ready to part. Jinnah chided himself for marrying a mere child.

Ruttie felt stifled by the need to keep up the charade of a hollowed-out marriage, which was devouring all aspects of her character except the role she was expected to play. “Try and remember me beloved,” she wrote to Jinnah “…. as the flower you plucked and not the flower you trod upon.” Her letter to Jinnah on separating is a damning indictment of unrequited love. “Darling, I love you. I love you – and had I loved you a little less, I might have remained with you.” Within a year of separating, Ruttie was dead – rumour has it, through an overdose of drugs. She died on her birthday – February 20 – at the age of 29.

Born at the dawn of the 20th century, Ruttie exuded the confidence and exuberance of one born to lead. But her gilded life remained imitative, out of context, a parody of an alien culture, lacking in the sense of purpose or deep roots, which are the bedrock of inner peace and happiness.

Rapid urbanisation and the tech explosion in India have spawned similar incentives today to live “out of context”, “over the top” lives, in insulated, comfortable, alien bubbles. But take heed of Ruttie’s lesson – nothing which is out of context is sustainable.

Sheela Reddy’s book is a treasure trove. A must-have for your bookshelf.

Sanjeev Ahluwalia is Advisor, Observer Research Foundation. He specializes in economic governance and institutional development.