Magazine

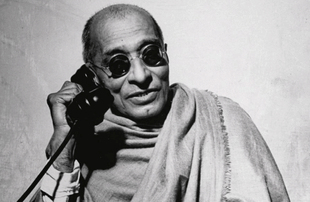

Rajaji, The Master Craftsman

Ramnath Narayanswamy

Dec 10, 2018, 11:00 AM | Updated 11:00 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Rajaji was indisputably a life of considerable accomplishment, something that was acknowledged even by his critics. In this article, the author writes a tribute to Rajaji the writer.

There are a number of stories that are not too well-known about Rajaji. Lawyer, elder statesman and writer, he was a towering figure of impeccable repute who commanded universal respect and was described by Mahatma Gandhi as “the keeper of my conscience.” Apart from writing several works of lasting impact in both Tamil and English, he was the composer of Kurai Ondrum Illai, a heartrending ode to Lord Venkateshwara, the presiding deity of the Tirumala temple in Tirupati. It was set to Carnatic music and sung by M.S. Subbalakshmi.

His was indisputably a life of considerable accomplishment, something that was acknowledged even by his critics. The first of the two stories that I am about to narrate is known only to the circle of Ramana devotees.

It is said when Gandhiji visited Tiruvannamalai before independence, he failed to visit Ramanasramam, the spiritual retreat founded by Sri Ramana Maharishi, despite exhorting a number of people who came to him in search of peace of mind to meet the sage. Gandhiji would invariably ask them to go to Ramansramam. During his visit, however, the Mahatma failed to make contact with the sage. When the sage was later questioned as to why the Mahatma did not enter the Ashram’s premises, the sage replied: “Gandhi would like to come here but Rajagopalachari was worried about the consequences. Because he knows that Gandhi is an advanced soul, he fears that he might go into samadhi here and forget all about politics. That is why he gestured to the driver to drive on.”

Here is the story as witnessed by Annamalai Swami, a close devotee of the sage: “In the 1930s, Mahatma Gandhi came to Tiruvannamalai to make a political speech. Since the organizers had selected a piece of open ground about 400 yards from the ashram, many people in the ashram had hoped that the Mahatma would also pay a call on Bhagavan. When the day of the speech came, I, along with many other devotees, waited at the ashram gate in the hope of catching a glimpse of Gandhi as he drove past. When he finally passed us, he was very easy to spot because he was being driven to the meeting in an open car. Rajagopalachari, a leading Congress politician who had organized this South Indian speaking tour, was sitting next to Gandhi in the car. As the car was moving very slowly, I ran alongside it and saluted Gandhi by putting palms together above my head. To my astonishment and delight, Gandhi returned my greeting by making the same gesture. The car stopped for a few moments near the ashram gate, but it started again when Rajagopalachari gestured to the driver that he should drive on and not enter the ashram.”

The second story is also connected to Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai. This incident was witnessed by the late Belagere Krishna Shastri, author of the spiritual classic Yega Has It All. It is a beautiful and extraordinary text.

This writer had the unexpected pleasure and privilege of meeting Belagere Krishna Shastri in Bangalore several times. Krishna Shastri was a staunch devotee of Sri Ramana Maharishi. In what follows, I recount one of his experiences. He told me how he visited Ramanasramam three times when the sage was still in his mortal coil. His second visit was in 1948. During this visit, the renovation of the Patalalingam in the magnificent Arunachaleshwara temple was to be inaugurated by C. Rajagopalachari, then Governor General of India. The distance between the ashram and the location of the Arunachaleshwara temple is a brisk walk of about 30 minutes.

To his surprise, Krishna Shastri noticed that there was no sign of festivity in the ashram. The Maharishi was in his usual posture with devotees around him. He saw Rajaji enter the ashram and prostrate before the Maharishi. For about 10 minutes, nothing happened. Supplicating himself before the sage, Rajaji asked the Maharishi if he would grace the inauguration with his presence. The Maharishi replied: “Why did you think what is here (in the ashram), is not there too (in the temple)?” The inauguration took place without the Maharishi.

But my main focus in this tribute to Rajaji is not Rajaji, the politician or Rajaji, the statesman but Rajaji the writer. He was an astonishing storyteller. There are several generations of young adults who have been enthralled by Rajaji’s recounting of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata which were published by the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan and has today gone into several editions. They continue to inspire people even today. As a raconteur, Rajaji was a master craftsman. His constructions go directly to the heart of the matter, the language is pithy yet compelling and compassionate and at every stage of the narrative there is an attempt to glean the insight from the story. It lends the narration an incredible power to impact the reader.

My first exposure to the Ramayana and the Mahabharata came from Rajaji. I read them both for the first time when I was about 10 years old; like most kids, I would read them many times over. I still do. My father was an avid reader of the Bhavan’s Journal and our house was strewn with publications from the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

Rajaji’s Ramayana and Mahabharata stood out in that collection. When I think of my childhood, I am first reminded of Rajaji and these two epics; they are irreversibly connected. I could never put them down. Rajaji had that rare gift to draw the reader into a conversation; if you read one chapter, it would leave you thirsting for more.

“In the moving history of our land,” wrote Rajaji, “from time immemorial, great minds have been formed and nourished and touched to heroic deeds in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. In most Indian homes, children formerly learnt these immortal stories as they learnt their mother tongue—at their mother’s knee; and the sweetness and sorrows of Sita and Draupadi, the heroic fortitude of Rama and Arjuna and the loving fidelity of Lakshmana and Hanuman became the stuff of their young philosophy of life.”

This helps to explain why Jayaprakash Narayan wrote: “Rajaji is one of the makers of modern India and architects of her Swaraj. Even at the hoary age of 80, he has a political influence on this country which is quite beyond the influence of the (Swatantra) party he leads. But it is not as a political leader—though he has reached a supreme rank in that sphere—that he will be remembered by later generations, but as a teacher of humanity. His deep insight into human nature, his extraordinary knowledge, his ripe wisdom, his capacity to make his way through a forest of inessentials and externals to the heart of a problem, all go to make him a timeless teacher of man. It is his commentaries on the ancient classics, Sanskrit and Tamil, his interpretation and exposition of religion, that will give him in history a far more secure place than his political endeavours and achievements.” May that ever be the case.

The author is a senior Professor at IIM Bangalore. He is completing a volume on Investigations from the Epics for Managers

Ramnath Narayanswamy is a senior professor at IIM Bangalore.