Magazine

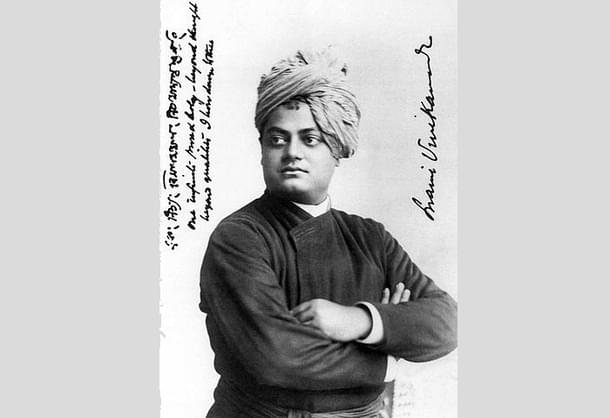

The Nationalist Monk Who Believed In Power Of Free Markets And Competition To Destroy The Caste

Hindol Sengupta

Mar 03, 2017, 08:29 PM | Updated Jan 12, 2021, 06:13 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The biggest political truth of Vivekananda’s life was that he came from a country which was under colonial rule. So what did he think of nationalism, which was sputtering to life all around him? What did he think of the idea of an independent India?

I think the answer to this, first, is given in a rather funny tale. It features in the writings of Marie Louise Burke, who, in turn, quotes from the notes of another prominent follower of Swami Vivekananda in America, Mary Tappan Wright, wife of Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard who facilitated Vivekananda's participation at the Parliament of Religions. The incident takes place when Vivekananda is staying at Annisquam, a little New England village. Vivekananda narrates a tale after supper.

“It was just the other day,” he (Vivekananda) said, in his musical voice, “only just the other day—not more than four hundred years ago…Ah, the English, only just a little while ago they were savages…the vermin crawled on the ladies’ bodices...and they scented themselves to disguise the abominable odour of their persons...Most horrible! Even now, they are barely emerging from barbarism.”

This shocked some of his listeners. One of them said, 'that’s not true, this was almost 500 years ago!'

Said Vivekananda:

“And did I not say ‘a little while ago’? What are a few hundred years when you look at the antiquity of the human soul? They were quite savage. The frightful cold, the want and privation of their northern climate has made them wild. They only think to kill...Where is their religion? They take the name of that Holy One, they claim to love their fellowmen, they civilise—by Christianity!—No! It is their hunger that has civilised them, not their God. The love of man is on their lips, in their hearts there is nothing, but evil and every violence. I love you my brother, I love you...and all the while they cut his throat! Their hands are red with blood.”

Dramatic fare for a sleepy New England audience!

This is not a well-known story in the Vivekananda chronicles. But more than his lectures and talks on nationalism, more than his serious tomes, this somewhat funny, almost mocking, over-dramatic story gives a brief but illuminating glimpse into the nationalist mind of Vivekananda, telling us in an instant what the man really thought. I read it again and again. Hidden in Mary Tappan Wright’s half-stumbling prose, in Vivekananda's sarcasm and his dramatics, it occurred to me that there could have, indeed most likely would have, been tremendous sorrow at the state of his country. Even as Vivekananda travelled through the free world, his evolved sensibilities would, no doubt, have considered how bereft his own home truly was. I see this incident as one of the most powerful recorded instances of the rawness of Vivekananda's nationalistic feelings, though conveyed in a half-joking manner. But he isn’t done that day yet.

“But the judgment of God will fall upon them,” says Vivekananda. “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord, and destruction is coming. What are our Christians? Not one-third of the world. Look at those Chinese, millions of them. They are the vengeance of God that will light upon you. There will be another invasion of the Huns,” adding, with a little chuckle, “they will sweep over Europe, they will not leave one stone standing upon another. Men, women, children, all will go, and the dark ages will come again.”

At this point, Mary Wright notes, “Vivekananda’s voice became indescribably sad and pitiful; then suddenly and flippantly...'Me, I don’t care! The world will rise up better from it, but it is coming. The vengeance of God, it is coming soon'’’.

How soon, he is asked here, is soon?Perhaps a thousand years, he answers. This brings some succour. Most likely, Mary Wright doesn’t quite recognise the humour when she jots down: “They drew a breath of relief. It did not seem imminent.”

“And God will have vengeance,” (said Vivekananda.) “You may not see it in religion, you may not see it in politics, but you must see it in history, and as it has been, it will come to pass. If you grind down the people, you will suffer. We in India are suffering the vengeance of God. Look upon these things. They ground down those poor people for their own wealth, they heard not the voice of distress, they ate from gold and silver when the people cried for bread, and the Mohammedans came upon them slaughtering and killing: slaughtering and killing they overran them. India has been conquered again and again for years, and last and worst of all came the Englishman. You look at India, what has the Hindoo left? Wonderful temples, everywhere. What has the Mohammedan left? Beautiful palaces. What has the Englishman left? Nothing but mounds of broken brandy bottles! And God has had no mercy upon my people be-cause they had no mercy. By their cruelty, they degraded the populace, and when they needed them, the common people had no strength to give to their aid. If man cannot believe in the Vengeance of God, he certainly cannot believe in the Vengeance of History. And it will come upon the English; they will have their heels on our necks, they would have sucked the last drop of our blood for their own pleasures, they have carried away with them millions of our money, while our people have starved by villages and provinces.”

But this “vengeance” that the monk speaks of—how will it come to pass? Who will bring it forth? Who will fight? Who will defeat the English? How will God get His revenge? Here again is a bit from Vivekananda’s teachings and writings, which are so recent, in a sense, they could have easily been written today. He says:

“And now the Chinaman is the vengeance that will fall upon them: if the Chinese rose today and swept the English into the sea, as they well deserve, it would be no more than justice.”

I am not suggesting that Vivekananda foresaw, Nostradamus-like, the rise of China. I am merely pointing out that he sensed the pulse of history, that, in the course of his travels, he had picked up nuances of global history and could, long before India received her independence, sense the changing world order to come. He was able to look far beyond the status quo of his environment, beyond current affairs, so to speak, and discern hints and signs about the future. Nations have risen and fallen throughout history—of what consequence is that to a yogi? Enough, this tale seems to suggest, if the colonial yoke is on you. Little wonder then that with such opinions, the “British government kept a vigil on him during his stay in England in 1896”, and “while Vivekananda was at Almora (in India), his movements were seriously watched by the police”.

This story is an interesting starting point to understand Vivekananda’s thoughts on nationalism. As a monk, Vivekananda saw India’s sense of self-rooted in spirituality more than anything else. His sense of the nation comes from religion. His sense of pride, dignity and self-preservation on behalf of the nation also come from spirituality. Vivekananda is consumed by the sense of the divine in everything he does. And so his imagination of the nation too is replete with the aura of God.

On 5 April 1894, the Boston Evening Transcript reported that Swami Vivekananda “made a profound impression here”. “Brother Vivekananda considers India the most moral nation in the world. Though in bondage, its spirituality still endures.” That could well be the summation of his nationalist pitch—and a constant urgent prodding that runs through his work for the people of India to shrug off their lethargy and discover their true potential and glory. “Arise, awake”—his words that have been featured on countless calendars are a clarion call to his nation, his way of vigorously shaking his fellow Indians by the shoulder.

Look at the names of many of his speeches and writings about India—“A plan of work for India”, “The problem of modern India and its solution”, “The education that India needs”, “Our present social problems”, “The work before us”. It is almost as if the more he travelled across the country and, later, the world, the more Vivekananda was convinced that in order to change the world, he must change India. That, in order to take the immortal message of Hindus to the world, he must uproot the sloth and malice that he saw among the Hindus around him.

He is the first modern Indian spiritual figure to give emphasis on the word “strength”. Without strength, in body and mind, there can be no national greatness, Vivekananda is telling us, and the search for God too is incomplete without strength.

“Struggle, struggle (he writes in a letter in 1894) was my motto for the last 10 years. Struggle, still say I. When it was all Struggle, struggle was my motto for the last 10 years. Struggle, struggle, was my motto for the last ten years. Struggle, still say I. When it was all dark, I used to say, struggle; when light is breaking in, I still say, struggle. Be not afraid, my children. Look not up in that attitude of fear towards the infinite starry vault as if it would crush you. Wait! In a few hours more, the whole of it will be under your feet.”

Vivekananda is rich and realistic today because his philosophy is both materialistic yet ascetic. Though he is constantly urging that “money does not pay, nor name; fame does not pay, nor learning. It is love that pays”—these transcendental exhortations would be almost meaningless without his engagement with the temporal. He writes:

“We talk foolishly against material civilisation. The grapes are sour… Material civilisation, nay, even luxury, is necessary to create work for the poor. Bread! Bread! I do not believe in a God, who cannot give me bread here, giving me eternal bliss in heaven. Pooh! India is to be raised, the poor are to be fed, education is to be spread, and the evil of priestcraft is to be removed. No priestcraft, no social tyranny! More bread, more opportunity for everybody!”

He urged: “Have fire and spread all over. Work, work.” Vivekananda’s nationalism is also intriguing because while he never really engaged directly with politics, he seems to have been cognizant of the fact that his work could, indeed would, form the base of a political consciousness, of a new spirit of recontemplating the nation. When he returned to India in 1897, he declared: “For the next 50 years, this alone shall be our keynote—this our great Mother India. Let all other vain gods disappear for the time from our mind.”

Historian Jayashree Mukherjee says, “Perhaps he was the only monk in history who could so vociferously relegate to the background, the god of his own religion for the greater cause of his country.” She believes that there are three modern proponents of the idea that India needs to be seen as a mother, as Bharat Mata—Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, author of Ananda Math (which had the song “Vande Mataram” in it), Aurobindo and Vivekananda. Aurobindo called Vivekananda “a very lion among men”.

“The tributes of great Indian nationalists and the statements of different political activists including revolutionaries of the colonial period as well as numerous government reports like the Tegart Report (1914), Tindall Report (1917), Ker Report (1917), and the Rowlatt Report (1918)” suggest, says Mukherjee, that Vivekananda’s impact and inspiration to Indian nationalism of the time was significant.

Vivekananda was an original. He was a man who called himself a “socialist”, though his lens and method were by urging men to know God and not economics. But Marx rejected God and Vivekananda was no Marxist. Benoy Kumar Sarkar, the social scientist, has argued that Vivekananda was a socialist, “not of the Marxian type, but of the Utopian brand”. In fact, Vivekananda understood how useful the free market was. He argued—as the Dalit social scientist Chandra Bhan Prasad does today, that “the only way to destroy the caste system in India was through free market”.

Vivekananda said:

“With the introduction of modern competition, see how caste is disappearing fast! No religion is now necessary to kill it. The Brahmana shopkeeper, shoemaker, and wine distiller are now common in Northern India. And why? Because of competition. No man is prohibited from doing anything he pleases for his livelihood under the present government, and the result is neck and neck competition, and thus thousands are seeking and finding the highest level they were born for, instead of vegetating at the bottom.”

Vivekananda was also keen on sharp, strong forms of nationalism. He found Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Shivaji Festival of particular interest and even agreed to preside over its Bengal edition once. Vivekananda met Tilak and even stayed at his Pune home for some time. He is known to have supported the idea that the Indian National Congress—inspired from America—should declare independence.

Mukherjee writes that Vivekananda’s youngest brother, Bhupendranath Dutta, who turned to militant nationalism, “regarded Vivekananda as one of the direct sponsors of militant nationalism” against the British Raj. Vivekananda himself is known to have said that Bengal was “in need of bomb and bomb alone”. There is also some evidence that Vivekananda wanted to gather and rouse the princely states against the British. He even met “Sir Hiram Maxim, the bomb-maker” to that end but realised that the country was not ready for such an armed revolt against the colonial rule at that time. He told the revolutionary Jyotindranath Mukherjee, aka Bagha Jatin, “India’s political freedom was essential for the spiritual fulfilment of mankind.”

At the same time, Vivekananda seems to have been cautious of involving himself or the Ramakrishna Mission in politics—a position the Mission steadfastly maintains even today. Later, he seems to have advised Sister Nivedita against starting a political party, even though she became increasingly active in the Congress. That one of his key disciples took such a keen interest in Indian nationalism perhaps is another indicator of the power of Vivekanandas teachings.

Beyond his wish to see India liberated from British rule, however, his primary desire, the one that fuelled most of his life’s work, was to see the reawakening of spirituality among Hindus. He believed it would impact not just the whole of Indian society—including the upliftment of non-Hindus who shared the same philosophical if not religious heritage—but also pave the way for India’s freedom. His argument seems to be, how can a nation, whose people realise the importance of the freedom of the soul, remain enslaved?

“In Asia,” wrote Vivekananda, “religious ideals form the national unity.”

Vivekananda, in Vikramjit Banerjee’s words, is a “radical traditionalist”. He attempts, constantly, to improve the institutions that he sees around him—not just the institutions, in fact, but the people themselves, for he believes that if people transform, the institutions will improve. And how can people transform? By rediscovering the foundation principles of their philosophies and faith.

“Millions of germs are continually passing through everyone’s body; but so long as it is vigorous, it is never conscious of them. It is only when the body is weak that these germs take possession of it and produce disease. Just so with the national life. It is when the national body is weak that all sorts of disease germs, in the political state of the race (the hint here is clearly colonial rule) or in its social state, in its educational or intellectual state, crowd into the system and produce disease. To remedy it, therefore, we must go to the root of the disease and cleanse the blood of all impurities. The one tendency will be to strengthen the man, to make the blood pure, the body vigorous, so that it will be able to resist and throw off all external poisons.”

Vivekananda is a monk, a man of religion, and therefore he sees “that our vigour, our strength, nay, our national life is in our religion”. He envisages the nation, its liberty, and its politics through the lens of spirituality—and, in the process, seeks to redefine spirituality itself.

“This is the theme of Indian life-work, the burden of her eternal songs, the backbone of her existence, the foundation of her being, the raison d’être of her very existence—the spiritualization of the human race.”

Most importantly perhaps, Vivekananda shows the best path— or what he felt was best in his context—we can take from the West and then apply or merge those principles with the greatest truths, as he saw them, of Indian philosophies. It is his ability to bring these two worlds together which makes Vivekananda’s vision for the nation so modern and important even today.

His nationalism does not shun the world; it embraces it. He soaks up ideas of freedom and politics from around the world and creates a nationalism which takes the most powerful ideas from around the world and connects them to a deep, old Indian ethos. Vivekananda’s nationalism taught us to approach and accept the world on our own terms and therein lies its value.

As he said,

“The ignorant Indian, the poor and destitute Indian, the Brahmin Indian, the pariah Indian, is my brother...The soil of India is my highest heaven, the good of India is my good.”

Hindol Sengupta is the author, most recently, of 'Life, Death and the Ashtavakra Gita', co-written with Bibek Debroy.