Magazine

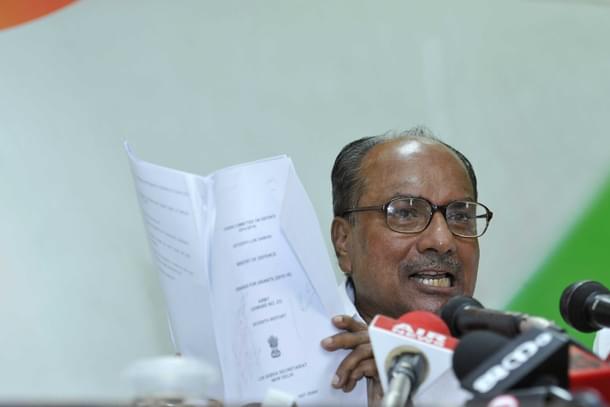

The Sins Of ‘St Antony’

Prakhar Gupta

Aug 04, 2018, 04:27 PM | Updated 04:27 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

During Arackaparambil Kurien Antony’s seven-and-a-half-year tenure, the longest-ever for an Indian defence minister, a joke was popular among analysts and journalists covering the security beat: the minister took a decision promptly only when he was offered a choice between tea and coffee.

Of course, this was said in jest. But given what went on at the Defence Ministry under Antony's watch, this is not very far from the truth.

Antony took over as defence minister from Pranab Mukherjee in October 2006, two years after the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) came to power. As one of Sonia Gandhi’s closest confidants, he was tasked with preventing a Bofors on the UPA. For Antony, a staunch party loyalist, who was brought back into the Congress fold — after he quit in the late 1970s — by Rajiv Gandhi, Pakistan was not the first victim of the Bofors guns, the Gandhis were. The last time the Gandhis had absolute control over the party and the government, the Bofors scandal had taken it away.

His image of ‘Mr Clean’ of Indian politics, which the media in Kerala had built meticulously for decades — came in handy for the Congress and the Gandhis. However, it was this image that proved disastrous for the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the three sword arms of the Indian military. With all his focus on the longevity of his clean image and preventing another Bofors, the ministry and the armed forces lurched from one crisis to another during Antony’s tenure.

The worst of these crises struck in 2011, when the then chief of the Indian Army, General V K Singh, filed a statutory complaint at the MoD on the issue of his official date of birth in the army's records. The voluminous statutory complaint sent to the MoD, the first ever by a serving chief of the 1.3 million strong force, exposed the deep fissures between the army and the government during Antony’s tenure. Antony, however, allowed the situation to worsen to a point where Singh moved the Supreme Court. On the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2012, just days after Singh retired as army chief, Antony called his actions “nuisance”.

This wasn’t the only time Antony allowed civil-military relations to hit rock bottom. In 2013, Antony forced the army to retract its statement on the brutal killing and beheading of five Indian soldiers along the Line of Control by the Pakistan Army, leaving the force incensed. After the incident came to light, the Northern Command of the army had issued a statement saying a Border Action Team of the Pakistan Army had carried out the attack. For reasons that remain unknown to most, Antony appeared in the Parliament the following day, claiming '20 heavily-armed terrorists along with persons in Pakistani army uniform' were involved in the attack.

In February 2014, navy chief Devendra Kumar Joshi resigned taking moral responsibility for a series of accidents, which had occurred during his tenure. In the past, and even under the UPA, chiefs of the three services and other senior officers were convinced not to resign when they offered to. In 2006, when Mukherjee was defence minister, the then navy chief Arun Prakash had offered to resign after the 'War Room Leak' scandal. Despite the fact that Prakash's nephew was involved in the scandal, a far more serious incident, his offer to resign was firmly rejected. Vice-Admiral Sureesh Mehta, deputy chief of naval staff and the officer directly in charge of the War Room, also continued to serve. Moreover, accidents were not unique to the navy. By some accounts, at least 28 planes and 14 helicopters of the Indian Air Force had crashed since 2011. Despite these facts, Antony hardly made any effort to convince the navy chief to not resign. To many, including those in the armed forces, it appeared as though the minister and the bureaucrats had found someone to blame for the accidents.

There were also times when Antony appeared more concerned about the survival of the government than national interest and security.

In 2007, when the Left parties — sympathetic to China — threatened to launch an agitation against the Indian Navy’s plans to hold Exercise Malabar with the United States in the Bay of Bengal, Antony chose to secure his party’s interests and not the country’s. Concerned that the protests by Left parties—supporting the government in New Delhi — would bring the fissures out in open, Antony recalled a senior officer and questioned the navy’s decision to hold the exercise in the Bay of Bengal. His logic: why hold the war game in the Bay of Bengal when the coast which it is named after, Malabar, lies in his home state of Kerala?

The same year, Antony again appeared supportive of the Left when it protested against the proposed Civil Nuclear Agreement with the US. His line: the Congress should not sacrifice the alliance with the Left front for the nuclear deal as it may need the bloc’s support after the next Lok Sabha polls.

Antony’s tenure was marked by slow acquisitions of equipment, cancellation of contracts and whimsical blacklisting of contractors, even on the ground of suspicion of kickbacks and association with a company that has been debarred. And while this may suggest that Antony successfully tamed corruption, the conclusion is far from the truth. While Antony did manage to prevent a Bofors on the UPA, he failed to stem corruption altogether. These cases come to mind:

One, the AgustaWestland helicopter scam. In 2010, the UPA government entered into a contract for 12 choppers worth Rs 3,600 crore from the Italy-based AgustaWestland to carry the prime minister, the president and other VVIPs. Despite alarm bells on kickbacks and allegations of corruption as early as 2009, Antony — known for blacklisting firms over tiniest suspicion — chose not to act until a court in Italy ordered the arrest of Finmeccanica (of which AgustaWestland is a wholly-owned subsidiary) chairman, Giuseppe Orsi, and AgustaWestland chief executive officer Bruno Spagnolini on charges that they paid bribes to secure the deal.

Two, the Tatra trucks scandal. In 2012, then army chief General V K Singh had revealed that he was offered a Rs 14 crore bribe to clear the purchase of a batch of 1,600 Tatra trucks in September 2010. Not only was Antony informed about the bribe offer by Singh, but he also received a letter from Ghulam Nabi Azad, a senior Congress party colleague and then health minister requesting action on the issue on behalf of UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi as early as October 2009. However, Antony claimed in Parliament that he did not act because a ‘written complaint’ wasn’t made.

Three, the Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) scandal. In a missile deal worth Rs 10,000 crore, signed just days before the 2009 general elections were announced, the Congress-led UPA government agreed to pay six per cent of the total cost — Rs 600 crore — as “business charges to IAI". The deal, with this unprecedented charge, passed through the Cabinet Committee on Security without Antony raising an eyebrow.

There was a clear pattern in all these cases. Even when he was aware of possible scams and scandals in the ministry, Antony remained quiet.

What explains Antony’s inaction? Most have arrived at the conclusion that he was inept. But again, can a politician, who has managed to build a clean image — unlike most senior members in his party — even as he successfully climbed the political ladder over a career spanning four decades, be inept? It is highly unlikely.

However, it could be his urge to maintain the image of Mr Clean, apart from preventing another Bofors, that explains his inaction. The cancellation of contracts, slow movement on new deals and preemptive blacklisting of contractors based on suspicion were the symptoms of his urge to come out clean at whatever cost. Fewer the deals signed, lesser the chances of his ministry being implicated.

Sure, this sounds outrageous. But numbers tell the same story. According to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Defence, there was a “steady decline” in the number of contracts signed in the 2007-08 to 2011-12 period. Only 84 defence contracts were signed in 2007-08, 61 in 2008-09, 49 in 2009-10, 50 in 2010-11 and 52 in 2011-12, the committee’s report says. The number of deals, as the report shows, started declining soon after Antony took over.

Antony’s inaction, in effect, was a strategy camouflaged as administrative ineptness. And at all times, his clean image came to the rescue.

When he left office in 2014, amid a barrage of allegations of corruption against the UPA government, Antony had no charges of corruption against him. He had largely succeeded in coming out clean from the ministry most prone to allegations of corruption and also managed to prevent a Bofors on the UPA.

But did it come at a cost of endangering India’s security?

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.