News Brief

Remembering Guru Nanak Dev: How Indic Perspective Tackles Questions Of Identity Like ‘Are Sikhs Hindus?’

Yaajnaseni

Nov 12, 2019, 08:19 PM | Updated 08:19 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

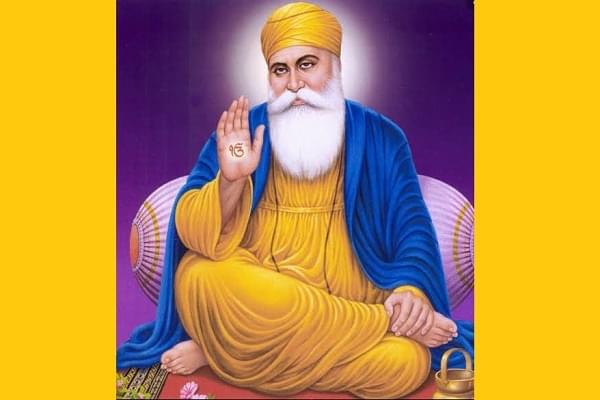

Today is the 550th Prakash Parv or birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev.

For us, this day shouldn’t only be an occasion of outwardly celebration but also of understanding and imbibing the teachings of saint Guru Nanak.

The words of the enlightened Guru to whom the brave Sikhs trace the foundation of their faith aren’t only a source of spiritual bliss but also provide the answers to many contemporary social and political questions that bother us.

Are Sikhs Hindus?

Before we move further, it is important to answer one such question that has raised much controversy lately: are Sikhs Hindus?

The short answer is, No.

Why? Because ‘Hindu’, ‘Sikh’, ‘Buddhist’, ‘Jain’ are modern political categories that are defined in such a way. These terms in themselves, in today’s times, don’t denote their meanings in the Indic framework.

Consider an example, today, if you find a particular document relating to someone which mentions they are Hindu, what can you gauge from that? Just the fact that they don’t identify as any other religion. You would have no idea how much Hindu they are in knowledge/belief/practice.

In this western framework, exclusivity under-grids the identity, that is, to identify yourself, you have to situate yourself opposite to the ‘other’. A famous example regarding implications of the western framework of identity imposed upon Indians was of Husseni Brahmins - Were they Brahmins or were they Muslims?

The Indic Perspective

In the Indic thought - which permeates Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, Buddhism etc - how one identifies oneself is of no significance as far as spiritual domain is concerned.

Under Indic thought, most, if not all, cultures believe that the body is the temporary abode of atman - is destructible and temporary, and therefore, the identities and relations associated with it are also temporary.

What defines the gati of a jeeva is Karma - one’s actions, and not how one chooses to identify himself (It is also important to note that the law of Karma doesn’t discriminate, any action - even towards plants and trees, stones and rivers - begets Karma).

Based on one’s Karma, a jeeva makes rounds of the world through different genders, races, castes, nationalities and situations. The freedom from this cycle of birth-rebirth is Moksha - a concept common to most, if not all, major Indic cultures.

Therefore, the concept of exclusive identity - and attachment to it - is antithetical to the spiritual progress within Indic framework. It is a symbol of Ahamkara, which has to be shed.

It is also important to note that the Indic concept of time is not linear (say, from the time of the prophet to the judgement day) but cyclical. Construction gives way to destruction and destruction gives way to construction. Men are born, then die. Civilisations arise and then fall. New technologies replace older ones. Customs, traditions also keep changing.

In all these times, the enlightened beings - those who have broken the shackles of Karma and become one with the Ultimate - from king Janaka to cobbler Ravidas - express their experiences and their journey for the benefit of others. These expressions are one and the same in the spiritual domain, but different in the cultural domain.

In cultural domain, these enlightened beings produce unique artworks, literature, music etc (the accessible forms of the Ultimate Knowledge), and others become responsible for protecting these. The students become responsible for protecting the knowledge passed on by their teachers. Such an arrangement is necessary for preservation, and it has more to do with Karma - what you do - than what you call yourself - the identity.

These unique cultures act as the little laboratories that preserve the Sanatana (the timeless - Akal) wisdom in their own ways. They interact with each-other to create a healthy debate, discussion and balance in the society, that saves it from rotting from inside. This is what makes the Sanatana Dharma, Sanatana (the timeless - Akal).

It is important to note that Ultimate Truth is many-sided, and the our enlightened teachers - operating in their unique context - provide unique solutions for protection and preservation of Dharma and attainment of Moksha.

These countless little laboratories, operating on common rules of Satya (the common commitment to the Truth), Ahimsa (non violence), and Dharma (righteousness), are also behind the remarkable resilience of the Indic civilisation in the face of persecution.

To summarise, Sikhs are not Hindus and vice versa. (or, by the Indic dialectics, Sikhs are Hindus and vice versa, both true).

One of the clues is that the great men of both the traditions didn’t feel the need to paste an identity on themselves in any significant way in their works. They had attained liberation, in the true sense of the word.

If we start reading these great men, we will understand how irrelevant, and stupid, this question of identity really is.

Despite the intense pressure from the hegemony of western model of religions that emphasises identity, property and quantity over knowledge and philosophy, hopefully, we will be able to get some clarity by the end of this article, by the grace of Guru Nanak Dev.

Sanatana wisdom and Sikhism

Guru Nanak Dev isn’t merely a great historical personality who was born in Nankana Sahib on Kartik Poornima in 1469 and left the earth in 1539 in Kartarpur, he is also the embodiment of the spiritual wisdom - the eternal knowledge - that is made available to the common people by enlightened beings - our great sants - from time to time.

Here is how this spiritual wisdom is described in Hymn 36, Japuji Sahib:

gi-aan khand meh gi-aan parchand, tithai naad binod kod anand

In the realm of wisdom, spiritual wisdom reigns supreme. The sound-current of the Naada vibrates there, amidst the sounds and the sights of bliss.

Naada is the Sanskrit word for "sound", or more precisely, the vibration that is the source of all sounds. Naada philosophy is based on the premise that the entire universe consists of sound vibrations. Naada is the hidden energy that connects the outer and inner cosmos. The words, Naada yoga, can be translated to mean "union through sound."

Guru Nanak emphasised Nam Japna - the repetition of God's name and attributes, as a means to feel God's presence. Here, the connection of Nam Japna with Naada becomes clear. By Nam Japa, one achieves the "union through sound."

The above hymn might have also reminded one of the phrase Satyam Shivam Sundaram from Yajurveda, and not coincidentally, as in the very next line, Guru Nanak Dev, giving a glimpse of the indescribable realm of spiritual wisdom (taa kee-aa galaa kathee-aa naa jaahi), as the source of incomparable Beauty.

saram khand kee banee roop, tithai ghaarhat gharhee-ai bahut anoop

In the realm of humility, the Bani is Beauty. Forms of incomparable beauty are fashioned there.

Readers will now see that how in such a simple yet immensely beautiful way, Guru Nanak Dev has summarised so many complicated concepts with his Bani. The indescribable becomes achievable for common people like us by the grace of this Bani.

The ultimate truth, or Satyam, or Satnam, is manifest in the form of Naada - that is what constitutes the realm of spiritual wisdom - this Naada pervades the whole cosmos and its essence is captured by the Bani. Therefore those who recite it, can achieve spiritual wisdom which is full of Ananda - bliss.

To further clarify, the very kind Guru also describes that the same Bani takes different form in different realms. In the realm of humility, Bani is the Beauty. In the realm of Karma, Bani is power (karam khand kee banee jor) and in the realm of wisdom, Bani is the supreme spiritual wisdom.

Therefore, Guruji clarifies that whatever realm one chooses, his Bani shall motivate him towards righteousness or Dharma (tis vich Dhartee thaap rakhee Dharam saal).

In the Gian-Khand, the Bani guides one to the true knowledge. In the Karma-Khanda, the Bani enables one to achieve power to establish Dharma and destroy the evil.

In the Saram-Khanda - the realm of humility - where one foregoes once own ego in devotion to the God, Bani is the source of ultimate Beauty - the beauty of the God’s name - that fills the heart of the devotee (tin meh raam rahi-aa bharpoor).

To further bring out the essence, we should discuss a little about the Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram (the following discussion is sourced from a previous article published in Swarajya).

Readers must remember that the nature of Brahman - the Ultimate Reality - the object of Moksha - is described as ‘Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram’ (the ultimate truth, the ultimately beneficial and ultimately beautiful). These three combined together, create Paramananda (the ultimate happiness).

A mumukshu (one who wants to free himself of the cycle of life and death, bonds of karma and the suffering, that, as Buddha said, is implicit in the samsara), can hold any one of these - Satyam - the pursuit of the Truth; Shivam - the pursuit of well-being; and Sundaram - the pursuit of beauty - and reach the Ultimate.

Those in the explicit pursuit of the truth are jnanamargi, the instrument is intellect and the object is knowledge. The pursuit of well-being involves practices that benefit the individual self as well as the whole humanity, along with other beings including the forests, the earth and the oceans - the instrument is Karma (Karmayoga) or Kriya (Kriyayoga) and the object is Kalyana.

The third is the pursuit of beauty. This is best characterised by the Bhakti marga. The instrument is bhava (emotions) and object is ishwara. A bhakt doesn’t want worldly success, Swarga, or even Moksha, but only the saanidhya of her beloved God. The instrument of beauty transforms our general, day-to-day pleasant experiences into those of divine nature.

It is important to remember that the distinction between these three paths is only from the frame of reference of samsara - a device for us common folks to understand. From the frame of reference of one who is enlightened - this distinction (more aptly, the perceived difference) melts away.

Therefore, the categorisation given above should not be construed to suggest water-tight experiences. A Yogi reaches the enlightenment through deliberate disciplining of the mind and the body, and Jnani reaches through Knowledge, and a Bhakt through Bhakti, but all three experience all three- Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram - and their works also reflect the same.

The words of the enlightened masters don’t compartmentalise the cosmos into mine and thine. Irrespective of the path taken towards enlightenment, their teachings cover all the realms of existence.

This unity despite diversity of paths is evident in the remarkable continuity of the timeless wisdom as expressed by the saints separated by hundreds of years and thousands of kilometres.

Take the example of Shankaracharya and Guru Nanak Dev.

In the hymns from Japuji Sahib, Guru Nanak Dev, all the while explaining the character of the God as Nirguna and Nirakar, tells us to recite the name of the Jagadeesh (lakh lakh gayrhaa aakhee-ahi ayk naam jagdees) as only His name can save one when death approaches (mannai jam kai saath na jaa-ay).

Similarly, Shankaracharya, a proponent of Advaita Vedanta, asks us to recite the name of Govinda (bhaj Govindam) as the mere knowledge of grammar wouldn’t save us when death approaches (nahi nahi rakshati dukrinkarne).

It is remarkable that both Shankaracharya and Guru Nanak give the description of God as timeless and formless, yet recite the names of Govinda, Hari, Rama, Jagadeesh etc.

The word Hari allegedly appears over 8000 times in Sri Guru Granth Sahib, the word Rama over 2500 times. Govinda, Murari and other names also appear several times.

We wouldn’t go into the concept of Avatara for the sake of length, however, the readers can themselves see that the unifying experience of enlightenment is all-inclusive.

(Some argue that Rama of Sikhism is different from the Ayodhyapati Rama, as former is timeless and formless. This confusion arises due to ignorance on both the sides. One might read Adhyatma Ramayana to understand the concept of Avatara and that Ayodhyapati Rama is timeless and formless.)

The character of liberation or Moksha is to make one free - and not bound to any particular words or description of the Ultimate - as that would be contradictory to the nature of the Ultimate itself.

Both Shankaracharya and Guru Nanak say that by his own grace, the God makes himself available to the devotees. Meaning, based on the capability and temperament of the devotee, the God himself shows him the path suitable for him.

Such thinking is behind the tolerance, peace and plurality in India despite immense diversity.

There are several other similarities between Japuji Sahib and Moha Mudgara. For example, both Guru Nanak and Shankaracharya warn us against outward religiosity and empty rituals (mannai mag na chalai panth; Udar Nimittam bahukrit veshah).

From the outsider’s perspective, the language of communication changes, the words change but the same experience of enlightenment is described by different Gurus and sants.

It is also important to note that the usage of the word Bani is indicative of the enlightened state achieved by Guru Nanak Dev. He has completely immersed himself in the Satnam and his Bani has become one with the Truth.

Therefore, seeing bani as mere words coming out of the Guru’s mouth would be a superficial understanding, instead it signifies the timeless wisdom communicated by an enlightened being.

Interestingly, a similar way of expression is found among the enlightened saints in the Vedas for whom ‘I’ no longer means their bodily-self, as the ‘aham’ has been united with the ‘Brahman’. An example would be Brahmavadini Vaak - a Rishika (woman saint) - mentioned in Rig Veda. The Ambhrni Sukta or Devi Sukta is attributed to her.

The description of the God - the Ultimate - by Guru Nanak and Vaak is also strikingly similar.

On the same lines, rishis born in times and places very different from that of Guru Nanak exhibit the same timeless knowledge - the Sanatana wisdom - that such enlightened beings, very kindly, make accessible for us through their works.

These enlightened beings were liberated - quite literally - from the narrow identities and descriptions that imprison our egos in this world. It would be a matter of grave loss if we ignore their words of their wisdom by being focused on superficial fights based on our perceived identities.

Sure, conflict is an unavoidable aspect of samsaric (worldly) existence, and some time or the other such conflict may arise due to samsaric reasons (political, social, economic and so on). The key is to not confuse and turn them into religious (in the Indic sense) conflicts, and solve them accordingly.

On the other hand, if we focus on the words of our great Gurus, and correspondingly, our own conduct, we will find these superficial fights disappearing as quick as the fog disappears when sun shines. Let’s us resolve to strive for such a Prakash on the 550th Prakash Parv.

A 25-year-old IIT alumna with deep interest in society, culture and politics, she describes herself as a humble seeker of Sanatana wisdom that has graced Bharatvarsha in different ways, forms and languages. Follow her @yaajnaseni