Obit

R Aravamudan: Pioneer, Leader, Veteran Of India’s Space Programme

Karan Kamble

Aug 12, 2021, 04:03 PM | Updated 05:59 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Ramabhadran Aravamudan was there before it all — when the Indian Space Research Organisation or ISRO wasn’t called that, when the core team of the newly set up Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) constituted just a handful of young folks, and before India had even materialised a station for launching rockets.

It was the early 1960s. He was a graduate of the Madras Institute of Technology and a young electronics engineer working at the Reactor Control Division of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) at Trombay. At that time, Vikram Sarabhai was on the lookout for young professionals with an electronics background to form a core group that would set up a rocket launch pad in the southern part of Kerala.

Paths crossed as Aravamudan, who explored the job opportunity after learning about it from a friend, was among the first set of engineers chosen by Sarabhai to sow the seeds of India’s space programme in 1962.

A simple motivation led Aravamudan to go down an unmarked path. “I was interested in the opportunity since I wanted to get away from the crowd and noise of Bombay, and green and peaceful Kerala offered a perfect alternative,” Aravamudan said in his 2003 address when ISRO marked 40 years since the launch of the first sounding rocket.

And so he left for Ahmedabad to meet Sarabhai, despite the reservations expressed by his DAE colleagues of leaving a permanent position for an uncertain future. “But my mind was made up,” he said in 2003. It was the start of an illustrious career at ISRO, humbly helping pave the way for the excellence of India’s space programme to shine through over the years.

It began with about a year’s training with the American space agency National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). He was among the four engineers that first went to Washington, DC, United States, to train at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

About three months later, he and his early colleagues were joined by three more INCOSPAR recruits, among them a young A P J Abdul Kalam.

“We were exposed to all aspects of sounding rocket launching. We were also coordinating with people at home and providing details of the range, the safety distances, building plans, electrical details and so on,” Aravamudan wrote in the ISRO publication From Fishing Hamlet to Red Planet: India’s Space Journey (published in 2015).

A sounding rocket is one used for research purposes, such as to collect science data in or from the upper atmosphere and/or to test out instruments.

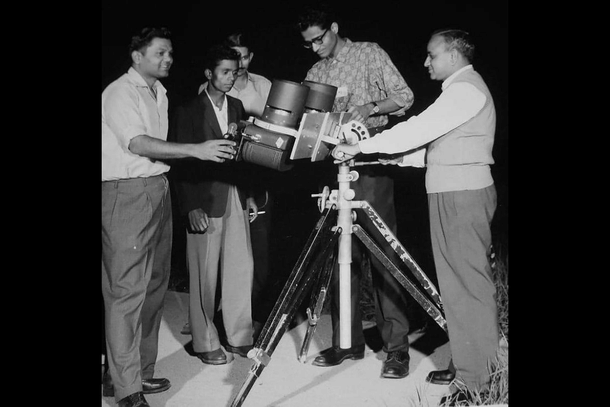

Next year, 1963, came India's first-ever rocket launch. The NASA-made Nike-Apache sounding rocket along with a vapour cloud payload, which was brought in from the United States, had to be lifted off. And here, Aravamudan had an important role to play.

“Aravamudan, whom we called Dan, was in charge of radar, telemetry and ground support,” Kalam wrote in his autobiography Wings of Fire, noting that Aravamudan was one of two colleagues “who played a very active and crucial role in this launch”. Kalam himself was in charge of rocket integration and safety.

This maiden launch on 21 November 1963 led to an increasing number of launches going into the second half of the decade, with Thumba being acknowledged by the United Nations in 1968 as a station that “will serve the interest of the international scientific community and all member States and contribute to international collaboration in creating opportunities for peaceful technical and scientific research”.

Around this time, Sriharikota, which is India's spaceport today, started to be viewed as ideal for rocket launches from the country. Aravamudan began developing the radar tracking system, besides other responsibilities, for the Sriharikota Range.

The Radar Development Project was fired up in 1971 with Aravamudan at its helm as the Project Director. It led to the development of two C-band medium-range radars that were successfully installed at Sriharikota in the latter half of the 1970s.

For his work in the area, he came to be recognised as a pioneer in the development of indigenous tracking radars. Radar tracking held particular significance in the military context.

Aravamudan also came to be known for driving the systems reliability and quality assurance activities at ISRO (INCOSPAR became ISRO in 1969). It was an essential aspect of India’s space activities because space systems, both on the ground as well as on rockets, had to be tested and greenlit independently before a space mission could proceed. Aravamudan was in charge of getting this important work off the ground.

Over the years, Aravamudan went on to serve Indian space science and engineering in many key positions, including as the Range Director of Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (first Indian spaceport in Thiruvananthapuram), Associate Director of Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Director of Satish Dhawan Space Centre (the spaceport of India) in Sriharikota, and finally Director of UR Rao Satellite Centre (then known as ISRO Satellite Centre) in Bengaluru. After this last stint in Bengaluru, he retired from ISRO in 1997.

“My personal journey has been synchronous with the growth of ISRO. Over the decades I was fortunate to be at the epicentre of crucial developmental activities, be it rocket technology, launch base establishment, spacecraft technology or the introduction of R&QA (Reliability and Quality Assurance) discipline in ISRO,” Aravamudan wrote in From Fishing Hamlet to Red Planet.

Along the way, he received many awards too, including the Aryabhata Award from the Astronautical Society of India in 2009 and the Outstanding Achievement Award of ISRO in 2010.

About 20 years after his retirement, he published ISRO: A Personal History in 2017, co-authored with his wife and veteran journalist and author Gita Aravamudan. It recounts the story of India’s space programme as it was built piece by piece by the many scientists — and he was the earliest of them — who happened to author the successful and inspirational story.

“The book will move not just his Indian reader but every citizen of post-colonised nations to recognise the kind of challenges that a developing nation will have to face when it wants to make itself self-reliant in science and technology,” writer and author Aravindan Neelakandan wrote in his review of the book for Swarajya, calling for the book, “one that elevates every Indian soul space high”, to be translated into all the Indian languages.

On Wednesday, 4 August 2021, Aravamudan passed away at the age of 84. He is survived by his wife Gita and children, and, of course, the glorious Indian institution that is ISRO.

Also Read: R Aravamudan’s Book On History Of ISRO Will Elevate Every Indian Soul Space High