Politics

Ayodhya Case: Why SC Bench And Muslims In General Must Read Sita Ram Goel

R Jagannathan

Sep 28, 2018, 01:16 PM | Updated 01:16 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Supreme Court’s refusal yesterday (27 September) to agree to the creation of a larger constitutional bench to rethink a 1994 verdict which held that “the mosque is not essential to Islam or the offering of namaaz” is correct – but partly for the wrong reasons. It is right because this was a needless red herring brought in by those who want to delay the start of hearings in the Ram Janmabhoomi case, which will decide whether the Ram temple can be built where the Babri mosque stood. Moreover, by trying to establish – before the Babri case is taken up – that mosques are an essential practice, the Muslim petitioners hoped to pre-empt any decision in favour of the mandir.

The decision, given through a 2-1 verdict, where the majority one was written by Justice Ashok Bhushan and Chief Justice Dipak Misra, and the dissenting one by a Muslim, Justice S Abdul Nazeer, is wrong for two reasons: it is not the business of courts to decide what is essential practice in a religion, whether it is Islam or Hinduism or Christianity. Those are matters of belief, faith and practice to be decided by the practitioners themselves.

However, Justice Bhushan rightly pointed out that the 1994 judgment was made in a particular context – the acquisition of the Ram Janmabhoomi land by the government after the demolition. That judgment also did not decide whether mosques in general are an essential part of Islam; it just underlined the point that no religious structure (mosque, temple or church) is immune to government acquisition, and the only thing that can prevent acquisition is if it were to be claimed that a particular mosque had special significance for a religion.

This is what the 1994 judgment (known as the Ismail Faruqui case) actually said in para 78:

“While offer of prayer or worship is a religious practice, its offering at every location where such prayers can be offered would not be an essential or integral part of such religious practice unless the place has a particular significance for that religion so as to form an essential or integral part thereof. Places of worship of any religion having particular significance for that religion, to make it an essential or integral part of the religion, stand on a different footing and have to be treated differently and more reverentially.” (Italics mine)

This is what bothers the Muslim petitioners, for it cannot be claimed that the Babri mosque had any special significance for the community. In Saudi Arabia and elsewhere, religious structures have regularly been demolished to give space for the expansion that special mosque, the one in Mecca. What bothers them is the reality that while the Babri mosque had no special significance for them, the Ram mandir in Ayodhya has enormous importance for Hindus as the deemed birthplace of Shri Ram.

It is also wrong for the court – and some of the Hindu petitioners – to treat the case as a mere property dispute and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) MP Subramanian Swamy surely is right to shift the goalposts by pointing out that the dispute is about the Hindu right to pray at Ram Janmabhoomi. Many Hindus regard it as an affront and a denial of their own even older belief that a temple existed where the Babri was constructed – and archaeological evidence supports this claim. They believe that the building of the mosque by Babar’s general on the temple’s ruins was intended to show Islam’s religious dominance over Hinduism. The demand for the Ram mandir is essentially about correcting this.

If the courts have any doubts over this, they should read two books by Sita Ram Goel (Hindu Temples: What Happened To Them: Volumes 1 & 2) to understand the overall context of the demand to build a Ram mandir in Ayodhya. The bench to be constituted to finally decide the Ram Janmabhoomi suit, as well as the key Muslim petitioners, should be presented copies of these books, apart from several others (of which more later) so that they know what the real issues are.

This brings us to the real underlying issue: can the courts, or even Parliament, decide this case to the satisfaction of all concerned? Whichever way the verdict goes, it is not going to make Hindus or Muslims willing to bury the hatchet and build a new relationship of greater trust in secular India. If Hindus win, and this is accompanied by triumphalist chest-thumping, it will be seen as a win for majoritarianism muscle and resented by Muslims. If Muslims win, it will tell Hindus that in secular India, even the courts are driven by minoritarian impulses, and unwilling to treat majority interests on a par with those of minorities. The sense of institutionalised discrimination against the majority will get reinforced.

The only way to ensure greater communal amity is through a mutual agreement between leaders of the two communities to allow the Ram temple to be built, in return for some concessions on the Hindu side on other issues, including possibly giving up claims to the temple sites in Mathura and Kashi, which are anyway debarred from a change in status by a law passed after 1992 by the Narasimha Rao government. The irony is that the Hindu claims are strongest in these two age-old religious centres. This in-your-face building of mosques, right next to where two of Hinduism’s holiest shrines exist, was surely a deliberate attempt by past Muslim rulers to demonstrate their religious dominance.

A compromise between the two communities, where the Ram Janmabhoomi land is shared between a mosque and a temple will be rejected by Hindus, for it means the historical record of Muslim rulers’ destructive iconoclasm will be given a whitewash.

If one were to step back and look at the genesis of this distrust, especially after 1947, one has to apportion a large share of the blame to Nehruvian and Leftist thinking, which has sought to shield Muslims in independent India from their own iconoclastic history. So, historians will now say any temples destroyed was the result of political necessity, and not Islamist religious fervour. And the Nehruvians would like to believe that a modern state must not make temples and mosques an issue today.

This is bunkum. No community or nation can run away from its past. Germans are not allowed to wish away the holocaust or the anti-Semitism of Hitler. The Chinese will never allow the Japanese to forget the rape of Nanking or other atrocities committed on its people during the period of Japanese occupation. Hindus will never be allowed to forget the damage caused by casteist discrimination. So, what is it about Islam that all historians are keen to shield present-day Indian Muslims from what got done earlier? Nobody can blame today’s Muslims for what Aurangzeb or Tipu Sultan did, but surely, they cannot be told that these rulers were not bigots.

Just as B R Ambedkar’s critique of caste and Hinduism should be required reading for Hindus, Sita Ram Goel’s two-volume study on the destruction of Hindu temples by Muslim rulers (Hindu Temples: What Happened To Them – A Preliminary Survey, and Hindu Temples: What Happened To Them – The Islamic Evidence) ought to be read by all educated Muslims. Arun Shourie’s Eminent Historians, which critiqued Leftist history that put a rosy tint on Islamic iconoclasm, and Ambedkar’s Pakistan, Or The Partition of India) must be read by all Muslims.

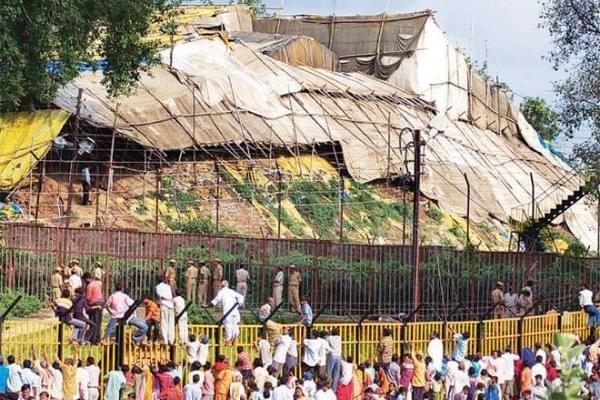

While present-day Muslims may well be aggrieved over the vandalisation and demolition of the Babri masjid in December 1992, they should also read two other books, Meenakshi Jain’s Rama and Ayodhya, and The Battle for Rama: Case of the Temple at Ayodhya. This will enable them to judge the demand for a Ram mandir in its right context.

It is significant that no “secular” or Left historian will even dare refer to these books, and that is why Muslims should read them. They will know that the Hindu case in Ayodhya is stronger than they think, and the Left has led them up the garden path by making then believe that there was no Muslim temple destruction on a large scale in pre-British Islamic India.

It is only with a real understanding of Indian history that Muslims and Hindus can finally bury the hatchet of communal discord.

Only truth can set us free from constant fratricidal conflict.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.