Politics

Congress Hope Of Opposition Unity Has A Few Basic Structural Problems

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Jun 10, 2023, 01:21 PM | Updated 01:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

All edifices, whether material or metaphorical, have to be built on a robust structure if they are to stand. Otherwise, they will collapse in a heap while under construction.

The Congress party’s quest for opposition unity in the run up to the 2024 general elections suffers from such a basic structural problem in three ways.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi is, however, sanguine, and believes that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) can be beaten by a united opposition. “Just do the math”, he says.

Yet, for all his dreams of opposition unity, the threefold truth is that, either the BJP doesn’t exist in a state, or the Congress doesn’t, or a dominant third force doesn’t need the Congress to beat the BJP. The reason is that general elections in India are actually far more bipolar than we realize.

Indeed, the number of seats where an alliance with the Congress could have aided a united opposition in defeating the BJP can be counted on one’s digits (hands and feet).

If we study the BJP’s victories in 2019, in those states where the dominant player is an unaligned regional party, the Congress’s vote share was greater than the BJP’s victory margin in only 19 seats.

It's a small list: seven in Uttar Pradesh, seven in Odisha, four in West Bengal, and one in Haryana.

Pertinently, no seat from Bihar or Maharashtra features on this list since the Congress is already in alliance with regional opposition parties in these two states.

And in Haryana, while an alliance with Dushyant Chautala’s party could have helped the Congress win in Rohtak, albeit by a whisker, Chautala is currently allied with the BJP.

Under these circumstances, it is difficult to understand what arithmetic Rahul Gandhi employed to declare that a united opposition could win on its own, because, either there is insufficient vote transfer from the Congress to the opposition kitty, or it is just not required to beat the BJP.

In simple English: is there any value addition from an alliance with the Congress, which would help other opposition parties defeat the BJP in enough strength to win a combined 272 seats? Simple answer: no.

Instead, the only way that can happen is if the BJP loses 10-15 per cent vote share in at least 60 of the firewall seats it held in 2019 (and not, to re-iterate, through an alliance with the Congress).

And this situation exists because, as explained at the start, the bulk of the votes in most of the seats have already been bifurcated between two poles, where the Congress is either an established party, already in a coalition, non-existent, or irrelevant.

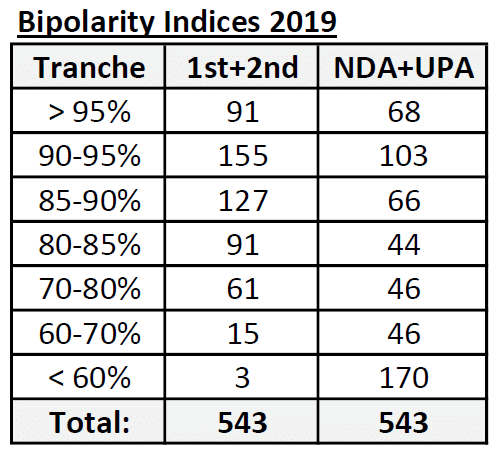

This is what the numbers say:

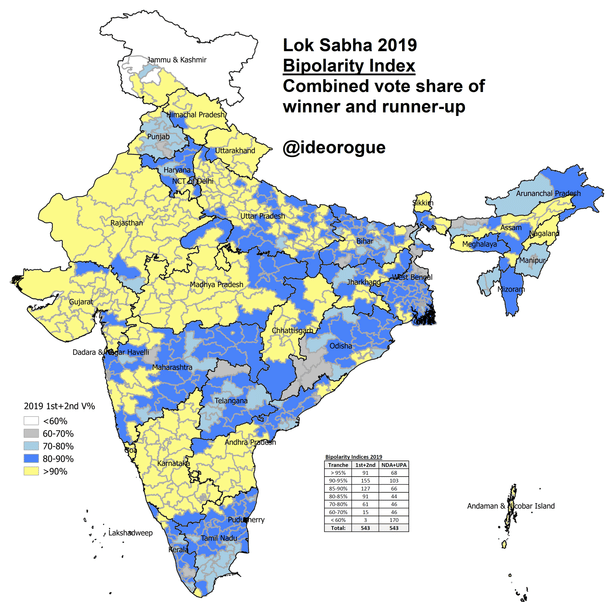

As the table above shows, 464 of 543 seats are clearly bipolar, with the winner and the runner up polling over 80 per cent of the votes cast. That is 85 per cent of the total. Just 18 seats have a bipolarity of less than 70 per cent.

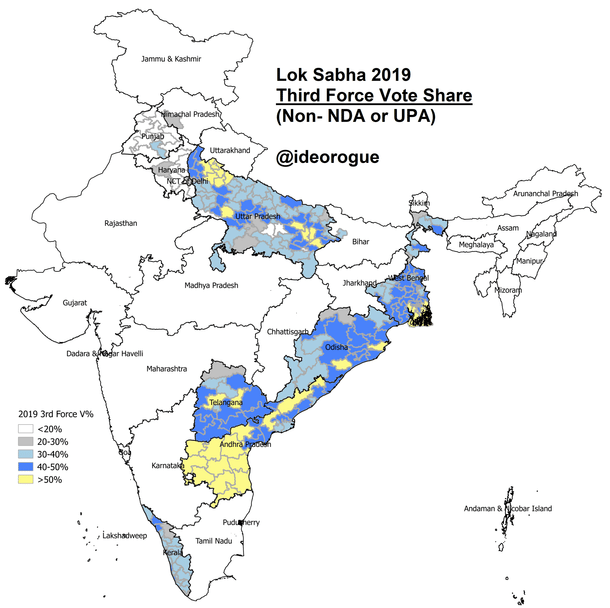

Of these 464 seats, 281 are direct contests between the two principal coalitions, in which, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won 236, and the BJP itself, 196. In the rest, the contest is mainly between the BJP and a regional party, as in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Odisha (and increasingly in Telangana), or between two regional parties, as in Andhra Pradesh.

But in these states, again, the Congress has been relegated to the periphery except for a few pockets in Telangana and northern West Bengal. Going by the 2019 results in Delhi, for example, even if the Congress struck an alliance with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), their combined vote share would be insufficient to dislodge the BJP in any of the seven seats there.

Similarly, and as mentioned earlier, even if the Congress were to improbably (but not impossibly) ally with the Trinamool Congress in West Bengal, or the Biju Janata Dal in Odisha, that would still change the outcome in only less than a dozen seats. And that is without factoring in a possible increase in the BJP’s vote share.

Likewise, they can’t align with the Communists in Kerala (they can and will, elsewhere) which means that, at best, they could have a tacit understanding in one or two seats like Thiruvanathapuram or Thrissur, where the BJP polls well.

But really, what is a handful of seats in West Bengal or Odisha in the grander scheme of things? Further, in other large states where the Congress is already in a coalition with regional parties, opposition prospects may brighten more because of new parties which joined it (like the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar, or Uddhav Thackeray’s party in Maharashtra), rather than any chimeral, additional contribution by the Congress.

The bottom line is that a material improvement in opposition performance can be wrought only if the Congress does better in those hundreds of seats where it is in direct confrontation with the BJP.

Whether the party can manage that, or not, is a question for the ages, but if it can’t demonstrate such intent and facility over the coming year, then its inability to force an outcome in its favour will be matched only by the apathetic response it gets from other opposition parties.

For, it is still a cleft-stick situation; if the Congress tries to regrow, it will be partly at the expense of the very opposition parties Rahul Gandhi dreams of aligning with; if it doesn’t, then its existing vote share will not be enough to defeat the BJP in adequate numbers.

This is the point about heightened bipolarity, which automatically lowers indices of opposition unity to avoid conflicts of interest, and presents an insoluble structural problem to the Congress.

You can’t vacate a space and then seek to re-enter it without disrupting the new equilibrium which evolved during your absence.

Thus, in conclusion, one reason why a number of opposition parties don’t appear too enamoured by Congress' calls for a united opposition is because they possibly believe that they can do better by taking on the BJP alone, while scavenging whatever is left of the Congress vote in their states.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.