Politics

Electoral Bonds Data: Smoking Gun, If Any, Should Worry Trinamool More Than BJP

R Jagannathan

Mar 15, 2024, 10:32 AM | Updated 10:32 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

From the rudimentary data on electoral bonds released by the Election Commission of India, the smoking gun is visible by its absence (see the raw data on all donors and receivers here and here).

The data, sent by the State Bank of India (SBI) to the commission, merely provides a list of donors, and the amounts encashed by various political parties over the 2019-24 period (12 April 2019 to 24 January 2024), and there is no obvious link between the two.

In fact, the only evidence of a smoking gun points in the direction of the Trinamool Congress (TMC), which was the second largest recipient of electoral bonds after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), receiving Rs 1,609.5 crore, compared to the BJP’s Rs 6,065.5 crore.

The half share of the BJP in the total proceeds of Rs 12,155 crore deposited by political parties with their banks is almost entirely explainable in terms of the fact that the party has been in power at the Centre and many states for the largest part of the period in question.

It is normal for corporates to want political and policy stability where they want to help the party in power to stay in power.

While a quid pro quo cannot be ruled out for donations to the BJP, this will take a long time to establish.

A simple linkage between contributor and party recipient is not enough to establish a quid pro quo, though one can certainly suspect it if the SBI provides unique codes linking the two, and someone further links the two sets of data to any policy or favours given to that party around the same time.

Since electoral bonds were made available only for 10 days four times a year (January, April, July and October), and for 30 days during Lok Sabha election years, these favours will have to be traced to those months before (or after) the donations were made.

Even then there is the additional issue of having to prove that the policy changes were made only to favour the donors. But any such data will be enough to set off a loud political pow-wow.

Most probably the anti-Modi media will be busy chasing those links and end up chasing its own tail, though we can expect a lot of innuendo and tendentious reporting.

Also, missing from the initial list of donors are the two A's — Adani and Ambani — the favourite whipping boys of the opposition.

It is highly unlikely that these two big businessmen did not contribute to the BJP or several other national and regional political parties, given their multi-state business interests, but they were probably smarter than the rest in hiding their donations through layers of front companies or even less known individual donors linked to these companies.

If there is a smoking gun in the data revealed so far, it points in the direction of the Trinamool Congress, that great white hope of the anti-Modi brigade.

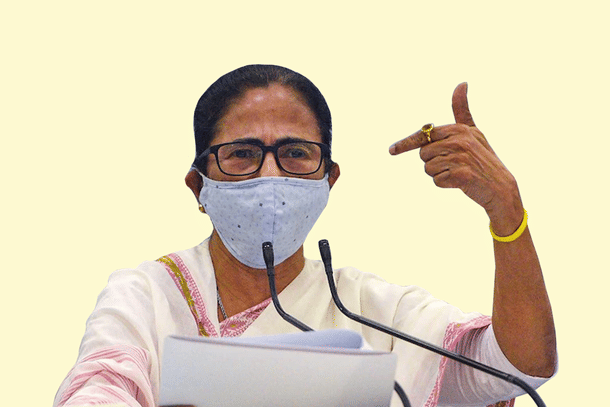

And the question is simple: how does a regional party whose state has a decaying industrial base, and whose Chief Minister was personally responsible for driving out the Tata Nano project from Singur in 2008, get so much money from corporates?

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Trinamool party cadres and political figures have been running various protection and extortion rackets in the state (read some of the allegations here, here, here and here). It takes no leap of imagination to suggest that corporates too must have faced demands from the party.

The SBI's request for more time to put out the data seems to have been designed to give the impression that it had something to hide — which is why the opposition smelt blood — but so far it has only led to a temporary cul-de-sac. It will take more time and media digging to get closer to the truth.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.