Politics

Muslim Reservations And Regional Authorities: RJD’s Bid To Reclaim Lost Ground In Bihar

Abhishek Kumar

Dec 24, 2024, 04:11 PM | Updated 04:11 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Sensing an opportunity to wrest back Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)'s hold on the Muslim vote bank, Tejashwi Yadav is recommending some unconventional policy measures, while hinting at an unconstitutional one as well.

Yadav is in the Seemanchal region — comprising Araria, Purnia, Kishanganj, and Katihar — for his 'Karyakarta Darshan Sah Samvad Yatra' (Worker Visit And Dialogue Yatra).

This region has 24 assembly constituencies, and in most of these seats, the Muslim community plays a decisive role during the assembly elections.

In 2020, Asaduddin Owaisi’s All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) spoilt RJD’s party by winning five seats there.

In his ongoing yatra, Yadav has been interacting with women and telling them about his proposed 'Mai Bahin Maan Yojana' (Mother Sister Respect Scheme), under which Rs 2,500 will be given to mothers and sisters.

But it is Yadav's comments on reservations for Muslims and the proposal to establish a Seemanchal Development Authority (SDA) that warrant a closer look. That's because it could have repercussions constitutionally and for the existence of Bihar as a state — especially in the wake of the party supporting the formation of a separate "Mithilanchal" state.

In one of the interviews, he was asked about the possibility of giving reservations to Muslims who are classified as backward in Bihar’s caste survey. However, Muslims who fall under the backward category do not get reservations because Article 341 of the Constitution of India does not allow their inclusion in the Scheduled Castes (SCs). On how he would proceed with their inclusion, Yadav said he would look into it.

Considering the RJD’s background and its position as a key player in the Indian National Inclusive Developmental (INDI) Alliance, Yadav's statement — despite not being overtly clear — is seen as his foray into the question of reservation benefits for Muslims.

In the past, the Congress, Trinamool Congress, and Left parties have supported this cause by introducing reservations in government jobs and public contracts. In May this year, the RJD supremo had advocated reserved seats for Muslims on the basis of backwardness and not religion.

Yadav choosing not to say no to the possibility of defining SCs in a way that would include Muslim castes stems from the political setbacks he has faced recently.

Although the RJD is known for its hold on Muslim-Yadav (M-Y) voters — who comprise nearly 32 per cent of the voters in Bihar — it was not the go-to organisation for Muslims in the 2020 assembly election, 2024 general election, and the recent bypolls.

While Owaisi’s AIMIM was a key player in 2020, during the 2024 general election, Yadav’s own experiment of modifying "M-Y" to "MY-BAAP" failed. The acronym "BAAP" refers to Bahujan, Agada (forward), Aadhi Aabadi (women), and poor. While the RJD succeeded in getting Kurmi-Kushwaha votes, Muslim votes moved to other parties, mainly the Congress.

In Purnia, Pappu Yadav was able to leverage his position and outmanoeuvre Tejashwi Yadav in securing significant Muslim and Yadav votes.

After the 2024 election, Purnia also witnessed bypolls for Rupauli, in which Bima Bharti, Pappu’s RJD rival in the Lok Sabha contest, was again given a ticket. Despite Pappu's appeal to vote for the RJD, Muslims (along with Yadavs) did not oblige.

Prashant Kishor’s yatra also gained popular attention. His old interviews criticising RJD for using Muslims as ‘lalten ka tel’ (oil used for lanterns) became a popular narrative regarding RJD’s M-Y push.

Kishor told Muslims that the RJD only uses the community for winning elections and does not care about their development. Not just in the media, he included this particular criticism in his local speeches, delivered during the Jan Suraaj Yatra, especially in the Seemanchal region.

Kishor was largely credited with Muslims not going the RJD way in the recent bypolls in Bihar. The RJD lost its bastion seats, like the Ramgarh and Belaganj assembly constituencies.

The setback confirmed the RJD’s fears around not selecting Muslim leaders for top places in the party. Seeing the low penetration of their community leaders in top positions, Muslim cadres actively shifted towards Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party (JSP), which provides avenues to move up the ladder.

JSP has also assured Muslims of at least 40 tickets in the 2025 assembly election. On the other hand, RJD provided only 17 tickets to Muslims in the 2020 assembly election.

RJD was suffocated, and sources said they needed a breather, which could only be engineered if Kishor’s momentum was broken.

After the bypoll results, Kishor allegedly insulted Javed Akhtar, JSP secretary in Muzaffarpur and a ward member, by asking him not to create a ruckus like RJD. A miffed Akhtar, along with 200 more Muslims, resigned from the party and burned Kishor’s effigy.

A few weeks later, Monazir Hassan, a former parliamentarian and minister in the Bihar cabinet, resigned from the core committee of JSP. Hassan is seen as the most popular Muslim face and a key organisational force in whichever party — RJD to BJP — he has served.

The developing trust deficit between JSP and Muslims is an opportunity for the RJD to strengthen its position. With this latest pivot towards Muslim reservations, Yadav also wants to tame the intra-alliance competition with the Congress for Seemanchal votes. The Congress wants to revive itself in Bihar by using Seemanchal as a stepping stone.

Apart from matching the Congress in asking for Muslim reservations, Yadav has also pitched for a special body dedicated to the development of the Seemanchal region, the SDA.

The need for SDA seems logical because multiple studies have shown that Seemanchal is one of the poorest regions in the country.

According to NITI Aayog's Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023, the Seemanchal districts rank among the poorest in Bihar. Araria has 52.07 per cent of its population classified as multidimensionally poor, while the corresponding figures for Purnia, Kishanganj, and Katihar are 50.70 per cent, 45.55 per cent, and 44.21 per cent, respectively.

The problem is low per-capita income and extreme inequality. For instance, Purnia and Katihar have well-developed urban clusters, but their rural areas pull down the statistics on human development and wealth parameters.

The region is trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty, electing leaders along communal lines, cursing them for five years after election, and re-electing them thereafter.

In Kishanganj, people ridiculed Mohammed Jawed for contesting again on a Congress ticket, but he emerged a winner for the second consecutive time.

The Seemanchal problem has its roots in demography and the politics surrounding it. A separate body does not seem to be the right way forward unless the underlying political issues are resolved. Perhaps no one understands this better than Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.

When Yadav was in an alliance with Kumar, he floated the idea of SDA to Kumar. “The CM said that if we set up a Seemanchal Development Authority, all other regions will come up with similar demands. Nonetheless, if the ‘Mahagathbandhan’ led by my party wins the assembly polls due in less than a year, we will go ahead,” said Tejashwi Yadav.

Kumar is correct here. Seemanchal is not the only region in Bihar that might demand special attention. Economic development in Bihar is highly skewed in favour of a few districts, foremost of which is the capital Patna. Even between the top two districts, the per-capita income (PCI) gap is too high.

According to the 2023-24 Bihar Economic Survey, Patna’s PCI (at constant prices) is Rs 114,541, while Begusarai comes second with a PCI of Rs 46,991. Apparently, taking out Patna’s contribution from Bihar’s GDP has a similar impact as leaving out Mumbai’s contribution from Maharashtra’s GDP.

Bihar's other regions have their issues with asymmetry. These places include the Kosi region (a segment of the Kosi-Seemanchal region), Bhojpur region, Tirhut region, and Mithilanchal region, among others. They also have intraregional overlaps with some districts, which is why their boundaries are still defined in a decentralised manner.

Kumar feared that a popular movement for more such bodies could arise from any of these regions, and he stood vindicated in September 2024 when (Tejashwi) Yadav himself promised that if given power, he would form the Mithilanchal Development Authority (MDA) for the development of Mithilanchal.

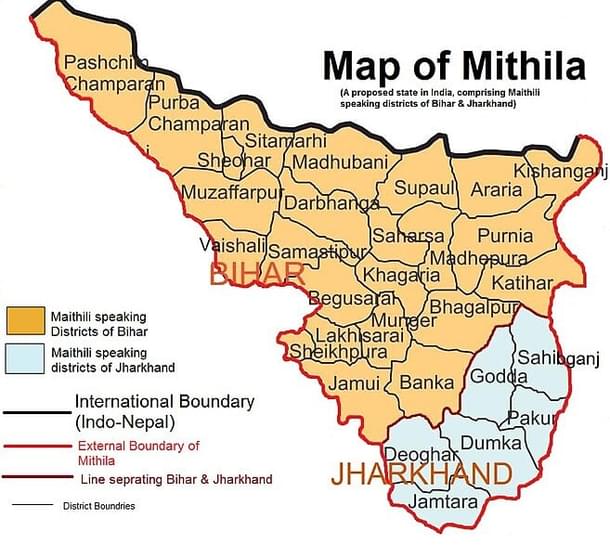

Though there are various conflicts among the pro-Mithilanchal lobby, by and large, the region comprises Sitamarhi, Madhubani, Darbhanga, East Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Saharsa, Vaishali, Madhepura, Begusarai, Munger, Bhagalpur, Samastipur, Sheohar, Supaul, Banka, West Champaran, Khagaria, and Seemanchal districts, among others.

The Mithilanchal region has about 33 per cent of Bihar’s population but contributes less than 5 per cent to the state’s GDP, arguably due to annual flooding, which takes away the productivity of 40 per cent of cultivable land.

The region has historically been mired by a lack of development and government neglect, despite some improvements in recent years.

It is no doubt the region needs special focus, and Darbhanga needs to be made the epicentre of it. There are efforts in this direction.

But Yadav and his party want to use this opportunity in a different way. A few weeks after Yadav’s proposal for an MDA, his mother and former chief minister Rabri Devi reinvigorated the age-old demand for forming a separate Mithilanchal state.

This demand is more than 120 years old and is mainly based on the unity of people who speak the Maithili language. Various movements, some democratic and some anarchic, like halting trains, were launched, but the demand was never met.

In recent years, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders like Kirti Azad, Gopal Thakur, and Ashok Kumar, among others, have also demanded the same.

The discussion intensified for a while after the Constitution was launched in the Maithili language.

While the senior BJP leadership has not spoken on the issue, the party and the broader National Democratic Alliance (NDA) will be in an advantageous position in the proposed state. The party is even stronger in key Mithilanchal places like Muzaffarpur, Darbhanga, Samastipur, and Madhubani.

The RJD and the INDI Alliance have to break NDA’s hold over the Mithilanchal region, which explains them speaking about an MDA and a separate Mithilanchal state.

The formation of a separate MDA, rather than taking the old, established route of equitable fund transfer and a push towards industrialisation, has political advantages for the party that brings it, rather than an economic advantage for regions.

Since Seemanchal is part of Mithilanchal, the proposal to form an SDA has to be viewed as a step in the direction towards MDA and ultimately Mithilanchal.

The angle of aggressive demographic expansion from Seemanchal to other regions of Mithilanchal in the long run, along the lines of West Bengal, is also a possibility worthy of deeper consideration. Santhal Pargana of Jharkhand, part of the original demand of Mithilanchal, has already met with this fate.

One major advantage of being in opposition is the agility to announce something off the socio-political radar and to mainstream it.

RJD fiddling with the Muslim reservation issue and the establishment of development authorities for Seemanchal and Mithilanchal is along these lines.

After all, administrative structure is not a hurdle for inclusive development; political structure is.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.