Politics

NEET: How Dravidian Parties And Fringe Groups Are Endangering The Future Of Tamil Nadu’s Students

SG Suryah

Sep 10, 2017, 04:17 PM | Updated 04:17 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

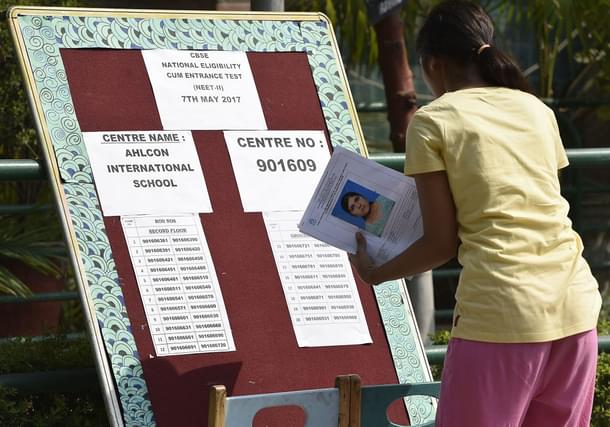

The National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for undergraduate medical courses has been the subject of a series of recent controversies in Tamil Nadu.

Regional political parties such as Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), firebrand fringe demagogues such as Seeman, and others have been accusing the Union government of ‘imposing’ NEET on Tamil Nadu’s students. Many conspiracy theories have been spun around this idea. For example, it has been suggested that the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Union government is using NEET to stealthily undo reservations for backward classes.

This article is an attempt to dispassionately analyse the origins, results, and impact of NEET on Tamil Nadu’s students aspiring to become doctors.

Let us begin with the origins of NEET.

Contrary to current narrative being encouraged by DMK and other elements, the origins of NEET belong to the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government era, of which DMK was a part.

NEET had been proposed to replace all other existing admission procedures for medical college seats back in 2010. It was proposed that state medical entrance exams, where they existed, be done away with, as also college interview processes and other intermediaries. This was naturally seen as an unacceptable incursion into the turf of many who stood to benefit from such processes. Over 100 petitions were filed in the Supreme Court against it. In July 2013, the Supreme Court quashed the NEET proposal citing violation of articles 19, 25, 26, 29 and 30 of the Constitution. This decision was then reversed by a Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court in April 2016.

Considering the timelines involved and other difficulties, seats in government medical colleges and government seats in private medical colleges were exempt from NEET in 2016. However, this exemption does not apply from 2017 onwards and NEET remains universal with over a million students writing it.

The second lie being spread by vested interests is that rural students from Tamil Nadu are at a severe disadvantage because of NEET. Let us examine this claim with the help of some data.

Between 2009 and 2013, merely 177 Tamil Nadu government school students secured MBBS admissions. That is, to repeat, only 177 students from government schools were able to get into MBBS course over a five-year period, and all this was before NEET. In 2014, this number was 32, in 2015 it was 35, and in 2016 once again only 35 students from Tamil Nadu government schools made it.

What these meagre numbers show is that students of private schools probably had access to expensive coaching facilities and were beating rural/government school students even before NEET. How come there had been little to no outrage about the meagre representation of government school/rural school students in the admissions paradigm before NEET?

Let us remember that until 2006, Tamil Nadu had its own state medical and engineering entrance examinations. So what you have now is the propaganda that a mere entrance exam severely discriminates against rural/government school students even as we know that only until 10 years ago Tamil Nadu had its own entrance exams.

So how did NEET perform in terms of rural and government school students getting into MBBS?

A cursory look at the district wise breakdown of admissions secured through NEET nails the lie that rural students are at a severe disadvantage due to the design of the exam. Consider the example of Namakkal, a district that had put 957 students into medical seats. This year, the district only managed 109 seats. How did this happen? The reason is that Namakkal is home to numerous “coaching factory” schools where students are made to ‘mug-up’ (i.e memorise) Plus Two syllabus without any care for analytical skills or critical evaluation. These students, until last year, were able to secure a disproportionate number of admissions because they usually did well in Plus Two exams and that was all that was needed. This year, under NEET, students are having to face the real world in a sense, and were seen struggling to compete.

So you have Namakkal, a ‘coaching factory’, that by any measure disadvantages rural and government school students seeing a correction.

But who gains when Namakkal loses? Ariyalur, a rather under-developed district, and other similar districts, have shown a good increase in the number of students they are able to send in. Ariyalur sent 21 students through NEET this year. Last year, it managed only four. The same is the case with Nilgiris, Thiruvarur, Sivagangai and Thiruvannamalai. All these districts have gained at the expense of Namakkal’s coaching factories. Surely, this is a more fairer system than before?

The third lie being propagated by fringe elements seeking to cash in on anti-NEET emotions is that NEET hurts the cause of social justice. The claim is that under NEET, students belonging to ‘forward castes’ secure more seats at the cost of ‘backward’ castes.

Once again, let us look at the numbers to understand the truth behind this claim. Some Tamil nationalist groups have even sought to spread a canard that reservations do not apply for admissions through NEET. Nevertheless such statements were quickly called out.

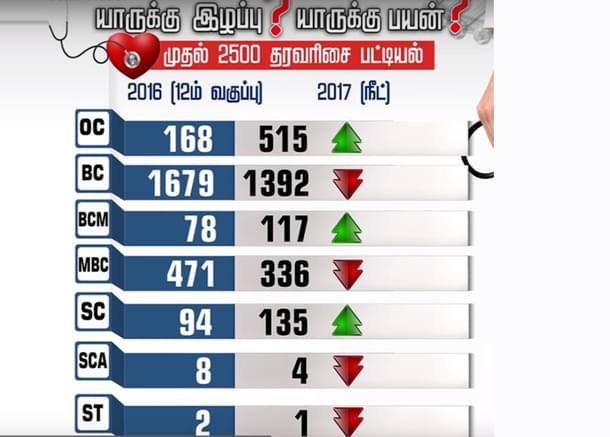

The propagandists sought to spread such lies based on the simplistic understanding of admission numbers. Consider the table below of community-wise take away of seats based on first 2,500 NEET/earlier rankings in Tamil Nadu. This was used in a television debate to highlight that Open Category (OC) students are securing nearly three times the number of seats under NEET and that this was evidence that ‘Brahmins’ have sneaked in stealthily through NEET. The assumption was that all OC students are Brahmins. (The table is used here to depict the narrative being propagated and is not necessarily fully correct). But what is the truth?

The truth is that only 193 seats out of 823 seats secured under this year’s NEET-based admissions were taken by ‘forward’ castes such as Brahmins and Chettiyars. The remaining seats were secured by backward castes (491), most backward castes (114) and scheduled castes (25). The term ‘OC’ in the table denotes open category and in states like Tamil Nadu, students entitled to reservations under BC, MBC and SC categories first compete for the OC pool and then compete for their reserved category pools. This technicality has been cleverly used to propagate an anti-NEET lie.

Let us now take a step back and try to understand how the state politics has dealt with the education system in general over the last few years. Surely, considering all the fuss being made about NEET, you’d think the body politic of Tamil Nadu would keep a hawk’s eye on the schooling system, syllabus, and others to ensure top class access to education for the state’s poor?

You’d be surprised.

Over 1,200 government girls’ schools do not have toilet facilities. Over 4,000 government boys’ schools also do not have an adequate number of toilets. About 40 per cent of government schools have leaky or no roofs. Seventy-seven per cent of government schools do not have adequate laboratory or computer lab facilities. Over 2,000 government schools have less than 20 students enrolled. More than 1,500 government schools have been closed. Some of this data is slightly dated (from 2014) but as recently as last year the Madras High Court came out with an extremely harsh series of statements on the state of government schools. (See this link)

You would think this is only about infrastructure. No, perhaps we can also look at how the state government has managed pedagogy and grading systems over the last 10-15 years.

The syllabus for Plus Two classes have not been updated for 12 years. In 2009, the state government introduced a syllabus system known as Samacheer Kalvi. The system ostensibly sought to provide an equal standard of education across Tamil Nadu’s schools. What it ended up doing was providing a venue for glorification of state’s political leaders and severe deterioration of teaching standards and learning outcomes.

Media house after media house have reported how the new syllabus system has severely degraded student’s learning outcomes (Report 1, Report 2, Report 3).

Since the government diluted the syllabus severely, we had students scoring unsually high marks. You can see how this resulted in a hilarious yet tragi-comic situation when students from the state cornered 75 per cent seats in a top Delhi University (DU) course. How? The DU affiliated Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC) admitted students using only Plus Two marks as the criterion and naturally, grade-inflated students from Tamil Nadu managed more than an edge in the admissions process. The college has since changed the process.

All this has caused parents to seek admission into CBSE (Central Board Of School Education) board schools across the state. No politician or activist has found it worth his time to take up these issues consistently – surely it is important to fix things in school and ensure the state’s students are competitive in future pursuits?

But all this is too much work for the parties in Tamil Nadu. Instead, over the years, they’ve gone after soft targets such as the Jawahar Navodaya schools that the Union government sets up across the country. They’ve claimed that since the schools teach Hindi as a compulsory subject, it would be tantamount to Hindi imposition and therefore such schools cannot be set up in the state.

Now, if you’d only spend a minute to see what these schools help other state students accomplish you’d understand why this is such a big deal.

Navodaya school fees for classes VI to Plus Two do not exceed Rs 300 even for higher classes. Boarding and food are completely free. Over 14,000 students from 598 Jawahar Navodayas attempted NEET entrance exams of which over 11,000 qualified. Of the 11,875 NEET-qualified students of Jawahar Navodaya school, over 7,000 have already secured medical admissions. None of them would be Tamil students because some parties here have made a voluntary school a topic of political difference.

You would think this extent of Hindi opposition would extend to opposing the establishment of new CBSE schools too. But what we have is that even close relatives of Dravidian party leaders run schools affiliated to CBSE and teaching Hindi. What’s more – a large number of CBSE affiliated schools have been allowed to be set up in the last few years. Is it anybody’s case that India’s endemic corruption and bribe-taking had nothing to do with the Dravidian parties allowing the establishment of these schools? Your guess is as good as ours.

So, we have a state government and political ecosystem that has allowed the schooling system to continuously deteriorate over the years. The system has stood witness to continuous grade inflation and erosion of standards. In the case of the SRCC BCom admissions, Tamil students were nearly the butt of grade inflation jokes.

Just to be clear, there are many things wrong with the NEET system. It is perhaps damaging in the long term because it does go against the federal character of the Indian union. Centralised testing cutting across the immense diversity of states in India is unfair for many reasons and has to be adopted, if at all, after careful study.

But what is equally true is that the continuing propaganda against NEET and the many falsities being spread in its name reveal much about Dravidian political discourse. It is hollow, farcical and does not really have the interests of Tamil students at heart. Worse, it is being spread by those that seek to further divisions between Tamils and the rest of the country. For this and this reason alone, it is worth standing up to such divisive fringe groups.

SG Suryah is State Secretary of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Tamil Nadu.