Politics

No More Excuses to Keep Netaji’s Post-45 Whereabouts a Mystery

Anuj Dhar

Jan 14, 2015, 03:12 PM | Updated Feb 12, 2016, 05:17 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

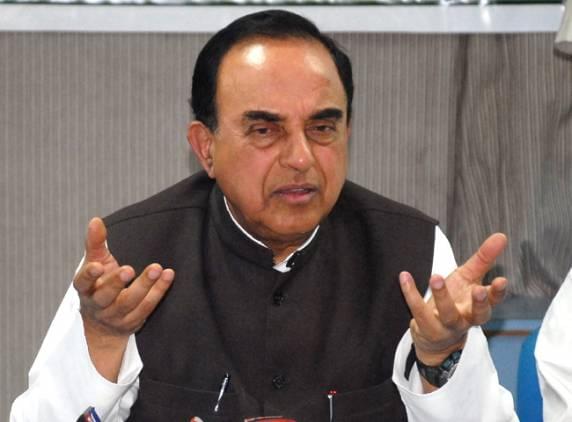

Records suggesting Netaji was alive post-August 1945 have leaked inadvertently. Now that Subramanian Swamy has reiterated his theory that Bose was killed in Russia, the government must come clean on the mystery. Modi’s government is better placed to declassify the files than all preceding governments.

The irrepressible Subramanian Swamy has created a flutter again by claiming in a press meet in Kolkata that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was killed in Siberia on Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s orders.

The outcry that has followed Swamy’s bombshell has pitted believers against disbelievers. Many think Swamy’s track record, especially his prescient observations in the Sunanda Pushkar case, lends credence to this latest charge of his. Others have rubbished the charge outright.

What is the reliability of the claim that Netaji was in Russia? Is there anything on record to suggest that he was there after his alleged death in Taiwan in August 1945, as we are told by mainstream historians?

After Bose was reported dead by his Japanese friends, the Government of India under the British created a group of intelligence and military officers to inquire into the Japanese claim. The Combined Section (CS) worked out of the Military Intelligence Directorate in the GHQ, India and was headed by Intelligence Bureau (IB) Deputy Director W McK Wright.

Rather early into the probe, the sleuths blew holes in the Japanese account. For one, there was no direct evidence of Bose’s death. No dead body, no picture, no documents — just the claim by a few ‘eyewitnesses’ that Bose had died while on his way to Tokyo to discuss the Indian National Army’s surrender.

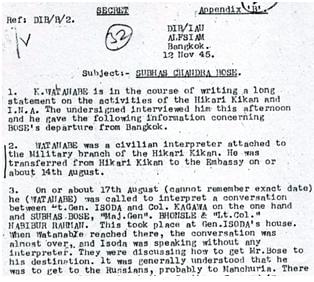

And then the IB found Kinji Watanabe, an interpreter attached to Hikari Kikan (the Japanese military organisation liaising with Netaji’s free India government), who had taken part in a secret meeting between Bose and Japanese military and intelligence officers just before the reported air crash in Taiwan. Watanabe told the IB that when he reached the venue, the Japanese led by Hikari chief Lt General Saburo Isoda were discussing “how to get Mr Bose to his destination”.

“It was generally understood that he was to get to the Russians, probably to Manchuria… With regard to Bose’s going to Russia, it was an understood thing… that he was going to hand himself up to the Russians,” reads the record of Watanabe’s interrogation declassified in 1997 by our government to mark free India’s 50th year. When governments undertake large scale declassification drives, some records that are otherwise meant to be hidden from public are released inadvertently.

Watanabe’s revelation was supported by several Japanese and INA officers, including those who were present in that meeting. General Isoda, who had worked out Bose’s last known flight, eventually conceded in the 1970s that “the purpose of his flight was to go to the Soviet Union and, with the aid of Soviet Union, he was to continue his independence movement”.

Long before World War II came to an end, Bose had been planning his next move as he could foresee the Allied victory. Contrary to general perception, Soviet Russia and Japan remained friends till about the end of the War, even though Russia was part of the Allied bloc.

In fact, Bose wrote a letter to the Russian Ambassador in Tokyo seeking Russian help in his fight to free India. This letter now lies in Moscow in former KGB archive — according to a Russian researcher, who saw it and copied its contents. The letter carries a comment from the Commissiar of State Security (NKGB) to the chief of the 5th division of the first command of NKVD — the forerunner of the KGB.

As to what advantage lay for the Japanese military in sending the Indian leader to Russia, Watanabe was able to recall Bose’s own words in another report:

Once I have been given an interview with the Russian Ambassador, I have perfect confidence in my success in persuading Russia to help our independence movement and at the same time I am sure that I can do something to improve the relations between Japan and Russia, and it might serve to decrease the menace Japan is feeling on the Manchurian side.

Also available in a file at the National Archive in New Delhi is the following assessment made by the Combined Section several months after Bose’s reported death. It was based on multiple, reliable sources, all of which ruled out Bose’s death:

In December, a report said that the Governor of the Afghan province of Khost had been informed by the Russian Ambassador in Kabul that there were many Congress refugees in Moscow and Bose was included in their number. There is little reason for such persons to bring Bose into fabricated stories. The view that Russian officials are disclosing or alleging that Bose is in Moscow is supplied in a report received from Tehran. This states that Moradoff, the Russian Vice Consul-General, disclosed in March that Bose was in Russia.

What have now gone missing are the post-1947 reports received by the Jawaharlal Nehru administration. For instance, a 1952 top secret note, now untraceable, conveyed the following from a former Bose aide-turned-Nehru loyalist and envoy to the foreign secretary:

A special messenger from Netaji came to see me on 16th from Bangkok with a letter from him asking me to get ready to secure transport from the Japanese and to leave for Manchuria, and to meet him there. He suggested that although the Soviets had declared war against the Japanese, it would be desirable to be arrested by the Soviet authorities in Manchuria because we could later negotiate with them and might persuade them to accept us as their friends and not enemies.

Despite all this and much more being on record, Prime Minister Nehru rebuffed suggestions to officially take up the matter with the Russians. The allegation is that Bose was left out in the cold. Once at a diplomatic gathering, he rebuffed a proposal to take up the Bose issue with the Russian ambassador. He said it was a “talk of chandukhana” — gossip in a den of opium addicts.

He was a lucky man as the records discussed above, and many more, were not in public domain back then. But then, there is much more that remains classified in our age. The Prime Minister’s Office alone has 60 files regarding Netaji, Rajya Sabha MP Sukhendu Sekhar Ray was informed last month. Are we living under the British rule that our government maintains secret files on the man Mahatma Gandhi called “Prince among patriots”? Would the Government of India dare to keep files secret on other national icons?

We must demand disclosure of every secret paper regarding Netaji, especially those held by intelligence agencies. We should do so for the very reasons heaven and earth are being moved to crack the mystery of Sunanda Pushkar’s death: truth, justice and transparency.

Of course, it has been many years that the Bose mystery has been going on and on. But one must appreciate that with the government hostility on one side and a lack of credible information on the other, a solution to India’s longest running controversy was not possible earlier.

For more than a decade, Anuj Dhar has devoted himself to resolving the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Subhash Chandra Bose. His 2012 bestselling book India's Biggest Cover-up (Netaji Rahasya Gatha in Hindi) triggered the demand for declassification of the Bose files.