Politics

Output-Outcome Monitoring Framework: A Critical Budget Reform

Urvashi Prasad and Shashvat Singh

Jul 22, 2019, 04:35 PM | Updated 04:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Over the last few years, the Government of India has undertaken several expenditure reforms, including the simplification of appraisal and approval processes as well as structural changes in the process of preparing the Budget itself. For instance, the distinction between plan and non-plan expenditures has been done away with.

Another key reform has been the development of the Output-Outcome Monitoring Framework (OOMF). This framework for FY 2019-20 covers major Central Sector (CS) and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) with outlays larger than Rs 500 crore, along with clearly defined and measurable output and outcome indicators as well as targets for the current financial year.

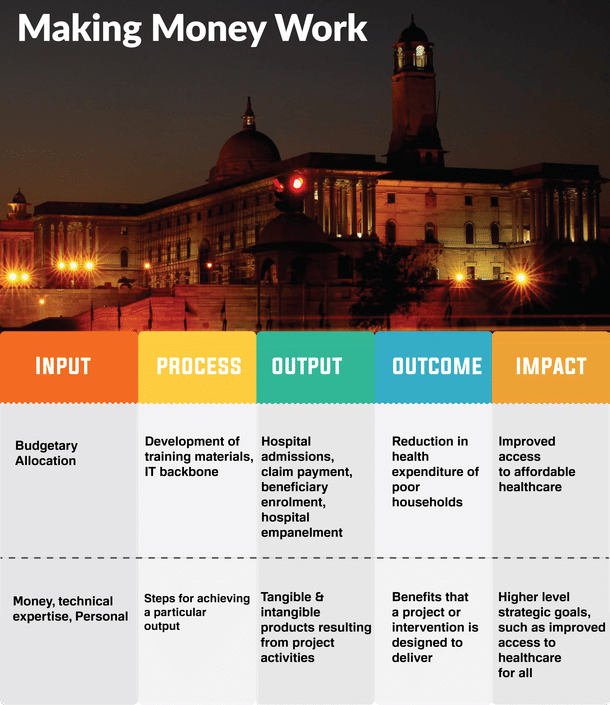

For instance, for the Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), which is a centrally-sponsored health insurance scheme, the financial outlay for 2019-20 is Rs 6,400 crore. The measurable outputs for the scheme include number of hospital admissions, number of identified beneficiaries, amount reimbursed for claims and number of hospitals empanelled. The targets for each of these respective outputs for the current fiscal year are 50 lakh, 5 crore, 4,000 crore and 16,500 respectively.

The outcome for this scheme is reduction in healthcare expenditures that push households into poverty. The overall impact of the initiative will be improved access to healthcare for poor and vulnerable households.

Similarly, under the National Rural Health Mission, the financial outlay for health system strengthening is Rs 27,039 crore for 2019-20. A key output for this intervention is expanding the basket of primary healthcare services provided through health and wellness centres. The target for the current financial year is to set up 40,00 such centres. A critical outcome for this initiative is improved utilisation of primary care services as well as screening and management of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). For 2019-20, the targeted outcome is screening 1.5 crore people for NCDs.

Figure 1: Illustration of OOMF with the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) Scheme

The rationale behind presenting outputs and outcomes, in addition to budgetary outlays, is that it enables greater accountability among the executing agencies of various government schemes. It also helps to significantly boost the transparency, predictability and understanding of the government’s development agenda, by facilitating an open, accountable, proactive and purposeful style of governance through a transition from mere outlays to result-oriented outputs and outcomes.

Further, such an exercise supports ministries/departments in tracking achievements against the defined objectives of their respective schemes.

Historically, budgetary allocations in the government have often not been linked to performance. OOMF makes a departure from this approach by paving the way for the government’s financial outlays to be linked to actual delivery of schemes. Other steps have also been taken in this direction over the last few years such as the linking of a portion of National Health Mission allocations for States to performance on NITI Aayog’s Health Index.

Such reforms are very much in line with international best practices. In the Netherlands, for instance, the “Accountable Budgeting” reform was introduced in 2013 to enable a more detailed parliamentary monitoring of expenditure. There is also an emphasis on ensuring that the lessons learnt from performance evaluation get prominence in Budget documents.

Similarly, in Austria, the performance budgeting system requires that the Budget outcome objectives are in alignment with international strategies, the federal government’s programme and sectoral strategies. Each outcome objective in the annual Budget has a detailed description and the line ministries are mandated to provide reasons for their choice of objectives.

In Mexico as well, the National Development Plan of the federal government enlists public policy priorities by defining the national goals over a six-year planning period. Budget programmes are linked to the achievement of sectoral objectives and those mentioned in the Plan thereby ensuring that public spending is in accordance with national priorities.

Further, in the United Kingdom, the House of Commons’ Scrutiny Unit supports Select Committees in examining the expenditure and performance of the government as well as the relationship between spending and delivery of outcomes.

Clearly, the development of OOMF is a step in the right direction. Moreover, the fact that it is a product of collaboration among a wide range of stakeholders, including the Department of Expenditure and NITI Aayog, augurs well for the future sustainability and improved effectiveness of this exercise.

Going forward, the outcome-based monitoring of schemes will need to be institutionalised and strengthened including through state-level capacity building workshops with the planning departments of states.

Ministries and departments at the Central level should also monitor schemes relevant to them, through their own dashboards, supported by the Development, Monitoring and Evaluation Office at NITI Aayog. Further, periodic sectoral reviews can be conducted to ensure that the various schemes of the government are contributing to the achievement of the overall policy objectives in sectors such as health, education, nutrition et cetera.

Further, the choice of outputs and outcomes for schemes can be refined in the future to capture performance more effectively along with mechanisms for triangulating data and ensuring quality.

Ideally, outputs and outcomes should be captured on a real-time basis so that course corrections can be made in a timely manner and the factors responsible for non-achievement of targets can be analysed systematically. This will also help design a smaller number of more effective schemes, as opposed to a larger number of schemes with modest budgetary allocations that might not produce the desired results and become cumbersome to manage.

The Government of India has already undertaken some steps in this regard by rationalising the number of Centrally Sponsored Schemes from 66 to 28 umbrella schemes. The latter, however, still comprise of a number of sub-schemes. Further rationalisation can, perhaps, be undertaken based on OOMF.

(Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal)