Politics

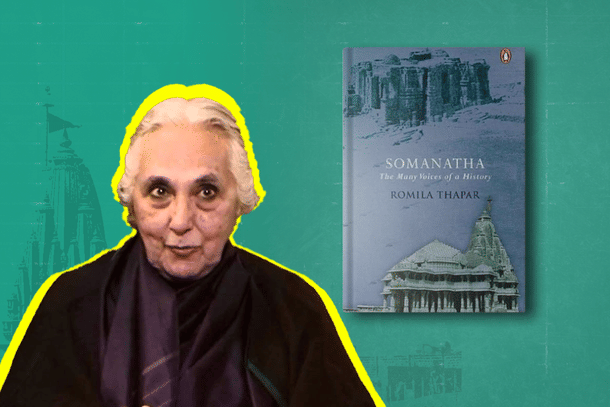

Thapar: Many Voices Of A History, Almost Always Wrong

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jul 12, 2023, 07:08 PM | Updated Jul 13, 2023, 12:39 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

"Beer Biceps," a podcast hosted by Ranveer Allahbadia, a popular YouTuber, has sparked controversy for an episode featuring the advocate J. Sai Deepak.

In a clip, now viral, from their interview, the YouTuber posed a hypothetical question to Sai Deepak, asking him to name three Indians 'who should leave India and never return'.

One of the names the Advocate mentioned was of historian Romila Thapar. Sai Deepak added that she, along with the two others, had harmed Indian interests in their own ways.

In this piece, we would only take the example of Prof. Thapar.

Opinions may vary on Sai Deepak's list and the nature of the question itself. Some may find it leading and unpleasant. The subjective nature of the question and subsequent list is open to interpretation.

However, it gives us an opportunity to objectively assess the claim made by the lawyer: that Thapar harmed Indian interests.

The historian in Romila Thapar

Romila Thapar had been associated with the 'National Council of Educational Research and Training' (NCERT).

The following is a sample from Medieval India, history textbook for seventh-standard students, published by the NCERT using Indian tax payers' money in 1988. The author was Romila Thapar.

Thapar's text consistently emphasizes negative economic relations when discussing Hindu temples, displaying an obsessive-compulsive inclination. Here is an excerpt specifically regarding the Cholas:

However not everyone was wealthy and prosperous. The labourers in towns and peasants in the villages were often very poor. They had to work very hard so that the king and others could live in luxury. Many of the shudras had a difficult life. The lowest caste were not even allowed to enter and worship in the temple.(p.15)

Below this, a picture of Thanjavur Brahadeeswara temple is given and the sub-section on temples follows thus: 'The king and the rich people gave large donations of money and land for the building and maintenance of temples.'

It ends with the sentence: 'The temple was not only a beautiful building but the store-house of great riches as well.' (p.15 & p.17)

These statements focus solely on the economic aspect of the temples, disregarding their spiritual or cultural significance. This emphasis, presented in a distorted manner, contributes to another narrative that unfolds in subsequent pages – the temple destruction by Mahmud Ghaznavi.

Romila Thapar informs the young readers:

Between A.D.1919 and 1025 Mahmud attacked only the temple towns in northern India. He had heard that there was much gold and jewellery kept in the big temples in India, so he destroyed the temples and took away the gold and jewellery. One of these attacks which is frequently mentioned was the destruction of the temple in Somnath in western India. Destroying temples had another advantage. He could claim, as he did, that he had obtained religious merit by destroying images.pp.25-6

And she also tells the kids:

Yet, although Mahmud was so destructive in India, in his own country he was responsible for building a beautiful mosque and a large library. He was the partron of the famous Persian poet Firdausi, who wrote the epic poem Shah Namah. Mahmud also sent the Central Asian scholar Alberuni to India. Alberuni lived here for many years and finally wrote an excellent book on India, describing the country and the condition of the people.p.26

One should note the not-so-subtle worldview emerging from the book.

The textbook portrays Hindu kings, such as the Cholas, as tyrants who oppressed their people, disregarded the poor peasants and workers, and lived luxurious lives. It states that temples were built exclusively for the rich and powerful, excluding Shudras, and that these temples contained vast riches.

Mahmud Gaznavi invaded these temples, seizing the wealth. He used this wealth to establish a large library, a beautiful mosque, and supported scholars, even sending some to study in India.

In essence, the textbook not only serves as an apologetic account for Mahmud Gaznavi but actively justifies the destruction of temples.

Cleverly, Hindu children are led to believe that their culture revolves around oppression, and that the destruction of their temples was deserved – Gaznavi was supposedly redistributing stagnant wealth obtained through the oppression of Shudras for the betterment of humanity.

The truth, however, is different.

The Chola territories had not only warrior-generals and ministers from Shudra castes but also saint-seers who established monasteries.

For example, there was Appar, born in a Shudra community to affluent parents. His future brother-in-law was a commander in the Pallava army and died in battle.

In Karnataka, the renowned Chenna Kesava temple of Somanathapura was constructed by a commander belonging to the fourth Varna.

Anabhaya Chola had a Shudra chief minister who became an authoritative figure in Vedic Saivite religion in Tamil Nadu.

Undoubtedly, Romila Thapar, being more knowledgeable than the present writer, would be aware of these facts. However, she chose not to present them to students.

The destruction of the Somanath temple holds another crucial aspect: the sacrifice of thousands of unarmed Hindu civilians who stood against the invaders to defend the temple, but were brutally massacred. It is a right of Indian children to be aware of their ancestors' sacrifice for their Dharma.

A history textbook funded by Indian taxpayers, covertly justifying temple destruction while neglecting the sacrifices made for the temples, essentially turns taxpayer money into academic Jizya. Romila Thapar and her associates perpetuate the legacy of temple destruction and Jizya in the guise of writing history.

Regardless of one's agreement with it, Sai Deepak's statement regarding Romila Thapar stands validated.

Her textbook writing has inflicted severe psychological harm on Indian children and her biased and perverse historical narratives continue to impact Indians.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.