Politics

The Congress Party: From Evolution To Devolution

Venu Gopal Narayanan

May 03, 2021, 07:13 PM | Updated 07:13 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

German naturalist Ernst Haeckel’s biogenetic theory posits that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.

It is a powerful aphorism which states that ontogeny, meaning the growth of an organism, mirrors phylogeny, or the evolution of a taxonomic group.

One example given in proof is of fish-like gill-slits, which develop temporarily in human embryos, implying a common path of development. While Haeckel’s theory was originally formulated for the zoological world, the evolution of the Congress party shows us that it is equally applicable to political science as well.

From fertilisation in 1885, through the puberty of the freedom struggle, and the maturity of independence, the comprehensive decimation of the Congress party, in the recent round of assembly elections, indicates that it has now firmly entered a stage of geriatric decrepitude.

As a development, that is neither odd nor unnatural, since it is the way of our world that those organisms, which fail to adapt to changing environments, are invariably deselected from a gene pool by nature.

Evolution foretells devolution.

In West Bengal, the Congress has been reduced to zero seats, and less than three percent of the vote share.

For a party which began with an open letter by Allan Octavian Hume, to graduates of the University of Calcutta, this annihilation represents an ironic final stage in its phylogeny, and marks a turning point in Indian politics.

Similarly, Puducheri might be a microscopic jurisdiction, but the defeat of the Congress there has major symbolic repercussions.

In Assam, a sizeable portion of its current vote share is in fact not its own, but supplied by Badruddin Ajmal and his AIUDF.

In Tamil Nadu, the Congress is, and will never be anything more than, a stepney of the DMK. And in Kerala, the party was spared the blushes of slipping down to single digits only by the goodwill of the Muslim League.

It is a systemic, systematic, pan-Indian progression, which first attained critical mass in the assembly elections of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, between 1987 and 1990, that eventually brought matters to this pass.

How did it come to this? The answer is a question: whom and what does the Congress party represent today?

In policy terms, the ‘what’ is a galling gallimaufry of self-contradictions and dead ends, which merits separate analysis. The ‘who’ is a lot easier to define, and is best typified by the state of the Congress in Kerala.

Once upon a time, the Congress was a Hindu-Catholic party dominated by Nairs, with strong social roots in Travancore and old Cochin State.

After Kerala was formed in 1957 by amalgamating British Malabar, a section of the Christians left to form their own party.

The Moplahs, mainly of Malabar, had their own outfit, the Muslim League, which sided then with the Communists.

The OBC Ezhavas, who are the largest social group in Kerala, never voted in bulk for the Congress, and still don’t.

Yet, over time, with the gradual institutionalising of identity politics, and due to evolving electoral exigencies, the Congress successfully devised an umbrella scheme, by which, they managed to retain their traditional vote base, while accommodating both the principal Christian and Muslim parties.

This confection, called the United Democratic Front (UDF), lasted fruitfully for decades (and still exists as a functioning coalition) until the Nairs started shifting earlier this century to the BJP, in disgust.

That is when it all came apart at the seams. Rather than pursuing the logical path, and seeking to win the Nairs back to their fold, the Congress, in absurd desperation, sought instead to consolidate their minority vote base.

This monumental decision, to try and somehow secure a popular mandate without the Hindu vote, ended up creating a bigger mess, because it only accelerated a Hindu exodus, further deepened social divides, and exponentially decreased the electoral prospects of the Congress’s primary strength – their Hindu candidates.

Nevertheless, things were fine as long as the Muslim League and the Christians’ Kerala Congress stood stoutly at the UDF’s vanguard, and the Hindu vote was split between the BJP and the Left.

A combination of electoral math, convenient delimitations, an imaginary victimhood, and calculated fear mongering, ensured that the UDF stayed in the fray with a chance.

But everything changed in mid-2020, when Pinarayi Vijayan won the UDF’s Christian Kerala Congress over to the Left. It was a brilliant strategic move, employed to offset the potential departure of some Ezhava votes to the BJP, which left the Congress up the creek without a paddle.

That rupturing departure created a bizarre anachronism, with a century-old national party, established by patriotic Nairs, being reduced to an abject subset of a regional Muslim outfit born of open cultural separatism.

It became so, that the Muslim League could exist without the Congress, but not the Congress without the League. Now, the Hindus weren’t with the Congress, and the Christians and Muslims didn’t need it.

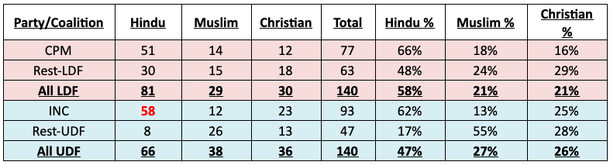

And yet, the Congress went ahead with their candidate selection for the assembly polls as if it was business as usual. Here are the numbers:

On the face of it, both the LDF as a coalition, and the Congress as a party, appeared to have adopted the same approach, by selecting around 60 per cent Hindus as their candidates.

But even a half-baked political analyst, with only superficial knowledge of Kerala voting patterns, knew that the Congress’s chosen 58 (marked in red in the table above), had the lowest chance of victory among any category; selection by party is never the same as selection by public, and woe betide anyone who thinks otherwise.

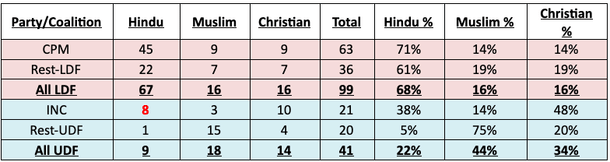

And that is precisely what the results showed: only eight Hindu Congress candidates out of 58 won (marked in red in Table 2 below).

The results were far worse for non-Congress Hindu UDF candidates; only one out of eight won, and even that victory had an intensely-emotional local flavour to it. In all, successful Hindu UDF candidates formed just one-fifth of the coalition’s massively diminished tally.

In fact, more Christians and Muslims won on a UDF ticket than Hindus did (32 of 41, or over three-quarters). Of these, the largest group of UDF winners were Muslims (18 of 41, or nearly half), most of whom belonged unsurprisingly to the Muslim League.

But the debacle doesn’t end there. The devolution of the Congress has reached such an extent that now, the party is actually pulling down the fortunes of not just their own candidates, but those of their partners as well, irrespective of demographics. The only ones to succeed are those who thrive not because of the Congress, but in spite of it.

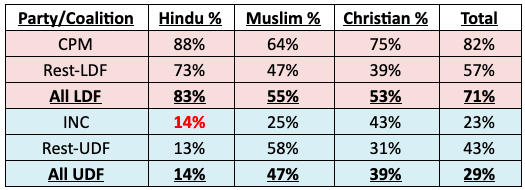

A win-ratio table highlights this vividly:

Where almost 90 per cent of the Left’s Hindu candidates won, only 14 per cent, or one-in-seven of the Congress’s Hindu candidates, did.

Compare that 14 per cent with the commendable 47 per cent win-ratio of Muslim UDF candidates, or even the still-decent 43 per cent win-ratio of Congress’s Christian candidates (considering that the Kerala Congress switched sides).

This is what the Congress has been reduced to in Kerala, and that is a reflection of what is happening to the party in other states, one after another.

From over a 12 per cent vote share in West Bengal in 2016, they are down to less than 3 per cent today – and that is in spite of an alliance with the Left, and a radical Islamist party.

In Assam, their vote share has reduced prima facie only by one percent – from 31 per cent to 30 per cent; but that is only on paper.

In reality, their decline would have been much greater, and their loss more cataclysmic, if not for a tie-up with Badruddin Ajmal’s AIUDF.

Sticking to our zoological metaphors, it is then tempting to ask if this denouement is the result of decision-making by party strategists with the intelligence of a zygote. Or, does the Congress genuinely believe that it can govern India without the Hindu vote? We can’t say, but the Punjab, which goes to the polls early next year, will provide a few answers.

Nonetheless, Ernst Haeckel, dead now for a century, would have been intrigued to see his theory of recapitulation being substantiated by the capitulation of a political phylum, with such remarkably close electoral parallelism.

For, this is the truth: A political party like the Congress, which chooses to selectively represent one community over others, ultimately ends up serving nobody. It is Darwinism with a difference, where unnatural selection engenders devolution, and invites eventual extinction.

All electoral data from Election Commission of India website.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.