Politics

Unease Of Doing ‘Business’: What It Takes To Open And Run A Private School In India

Arihant Pawariya

Aug 26, 2018, 04:44 PM | Updated 04:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Narendra Modi government is seized of the importance of ensuring the ease of doing business in the country and rightly so. Since 2015, it has taken a series of concerted reforms to climb on the World Bank’s annual rankings. The country’s big jump from 142 to 100 in just three years is testament to the government’s efforts.

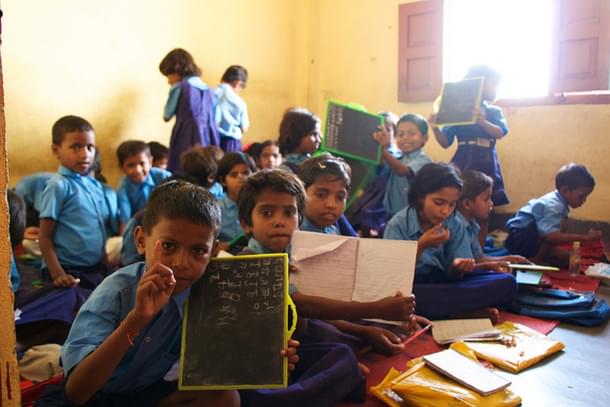

A similar if not more urgent initiative is required in facilitating the ease of opening and running a private, unaided school. Though many may frown upon labelling education as a business, but this is all the more reason to show urgency in liberalising the norms and regulations governing the establishment and administration of private schools. As India’s middle class is expanding, millions of children are leaving government schools and opting for private ones. With time, this trend is likely to get stronger as more and more parents become financially empowered enough to afford private schools.

However, since the passage of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, ease of opening and running a school has become a nightmare.

On the digital and print pages of Swarajya, this writer and others have spilled enough ink detailing the ills ailing the RTE Act. We have repeatedly criticised the policy of keeping minorities out of ambit of the act in toto; important sections like number 12 that mandates 25 per cent quota for students from disadvantaged groups/weaker sections in private unaided non-minority schools; section 13 that bars any kind of screening for admitting students; section 16 which allows mandatory promotion to the next class irrespective of the performance and learning; and so on.

However, one important aspect of the act that has escaped the much needed scrutiny is the set of regulations surrounding the recognition of a school which is the fundamental requirement to run a school. Sections 18 and 19 of the RTE deal with rules and restrictions in this regard.

These state that no private school shall be established or run without obtaining a certificate of recognition from the appropriate government authority on fulfilling certain norms and standards as laid out in the Schedule in such form and manner, within such period, and subject to such conditions as laid out in rule 11 and rule 12 of “Model Rules Under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009”.

What are the norms and standards set out in the Schedule? First, the minimum number of teachers a school must have from classes I to VIII depending on the strength of the class. Second, the building requirements (kitchen, playground, number of classrooms, etc). Third, minimum number of working days in a year. Fourth, minimum number of working hours per week for the teacher. Fifth, use of teaching aid for each class. Sixth, library. Seventh, play material, games, and sports equipment.

What do the rule 11 and 12 of Model Rules say? After conforming to the above norms, every school has to fill out Form 1 declaring that:

- the school is run by a society registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 (21 of 1860), or a public trust constituted under any law for the time being in force;

- the school is not run for profit to any individual, group or association of individuals or any other persons;

- the school conforms to the values enshrined in the Constitution

- the school buildings or other structures or the grounds are used only for the purposes of education and skill development;

- the school is open to inspection by any officer authorised by the state government/local authority;

- the school furnishes such reports and information as may be required by the Director of Education/District Education Officer from time to time and complies with such instructions of the state government/local authority as may be issued to secure the continued fulfillment of the condition of recognition or the removal of deficiencies in working of the school

Apart from these, there are eight tables of details to be filled in Form 1 such as:

Then the District Education Officer (DEO) carries out an inspection to see if the requirements have been met and give the certificate of recognition. However, it is temporary, valid for three years and is for primary classes i.e. up to standard VIII. For higher classes, there are separate, and similar taxing rules. Those who run schools without obtaining a certificate of recognition can be fined up to Rs 1 lakh and Rs 10,000 per day.

As if these onerous requirements, especially the ones highlighted in preceding paragraphs, were not enough, it is pertinent to note that these are merely those mandated by the central act. The states have their own, additional layers of regulations. Most prominent of these is ‘Essentiality certificate” aka the ‘no objection certificate’ awarded by the state government’s Department of Education every five years.

Even bye-laws of central boards like the CBSE insist on this prized possession as preliminary necessity before giving affiliation to schools. On top of all this, there are permissions and plans - building, health, water, land use permitted, etc - to be sought from municipality.

The situation is so bad that even elite schools with decades of reputation of delivering great service and education have to face extreme levels of bureaucratic red-tapism. Sachin Tendulkar’s school Shardashram Vidyamandir wanted to amend affiliation board from SSC to ICSE for Class 1 to Class IV and also wanted to change its name. Both the requests were dismissed by BMC officials stating that it has given NOC for SSC board till 2020 so it must continue with the same! How dare the school thought that improving students’ learning ability (by changing the board as saw fit by the school) was more important than asking busy BMC officials to fill out another form.

If this is the condition for established players who can be treated in such a manner by a municipal corporation, one can imagine what effect they will have on genuine players willing to enter the field. The regulations can induce bouts of trauma into even the most spirited of edupreneurs.

The language of the RTE Act and other rules indicates that the State is more concerned with reigning in the growth of private schools than facilitating right to education for everyone in reality.

While the regulations provide for elaborate monetary punishments which can even lead to closure of the school for not getting the recognition, there is no penalty on the government officials for their failure in giving the certificates in time even when schools meet all formalities. The Haryana government is yet to grant recognition for around 3,200 private schools operating since 2003 in the state. Without recognition they can’t even apply to the Haryana board for affiliation. Wonder why no act penalises the government, say Rs 10,000 per day per school, for each day’s delay in granting recognition (or rejecting it as the case may be)? Even if these schools are given recognition, it will only be for a year. The situation is similar in Odisha and Kerala too. Thousands of schools in the country go through such penance every year with the sword of ‘threat of closure’ hanging over their heads.

Also, the government can announce any new set of additional arbitrary conditions as the Uttar Pradesh government did recently when it made it mandatory for all schools to install CCTVs and biometric machines for attendance to seek recognition from the UP board.

And if the schools protest, the government can pass an order ruling that agitating against the government can lead to withdrawal of recognition as the Chandigarh education department did this year.

Such a regime is bad enough for any business. It’s suicidal to have it in private education sector which is the only hope left for the lower middle class and poor to climb up the social and economic ladder. Every day we continue with this system, we are inflicting great damage to the students from the lower strata of our populace who are disproportionately enrolled in the failed government schools. In its zeal to put a leash on private schools in the name of curbing profiteering, what the government has achieved is monopoly of those who are now experts at gaming the system through underhanded ways and means. The genuine educationists and philanthropists dare not enter the market.

What can the Modi government do? For starters, it can launch national ‘ease of opening and running a school’ rankings. Second, it can reform the norms and procedures needed for recognition mentioned in the schedule at the back of the RTE Act. It can be done by a simple government notification as section 20 of the act mandates. There is no need for ratification by the Parliament.

To realise the goal of universal quality education, which is affordable too, the state must facilitate proliferation of private schools leading to competition. This will do more to curb profiteering than any fee regulation act ever could.

Arihant Pawariya is Senior Editor, Swarajya.