Science

How Ladakh Became India’s Testing Ground For Human Habitation Beyond Earth

Karan Kamble

Feb 08, 2025, 07:56 AM | Updated Mar 03, 2025, 04:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A key scientific experiment crucial to India’s human space exploration future took place in Ladakh in November 2024.

This "space analogue mission" aimed to replicate, as closely as possible, the extreme environmental conditions of the Moon and Mars to study how human life could adapt to such habitats.

The 21-day mission was designed to simulate life in an interplanetary habitat, with the goal of preparing for a future where humans — perhaps Indians — might live on a base station beyond Earth.

Given that the Moon and Mars are likely to host humanity’s first extraterrestrial outposts, these celestial bodies naturally became the focus of such simulations.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), a collaborator on this mission, has ambitious plans: launching the Bharatiya Antariksh Station — India’s version of the International Space Station (ISS) — by 2035 and landing an Indian astronaut on the Moon by 2040.

Before these historic milestones, India’s Gaganyaan mission will mark its entry into human spaceflight. Expected in 2026, this mission will send up to three Indian astronauts into orbit 400 kilometres (km) above Earth for a seven-day journey.

Across all these missions, the recurring theme is space habitation. Preparing for extended human presence in space requires thorough groundwork, which starts on Earth through analogue missions that simulate extraterrestrial environments.

This is where the Ladakh Space Analogue Habitat comes into play.

Ladakh Space Analogue Habitat

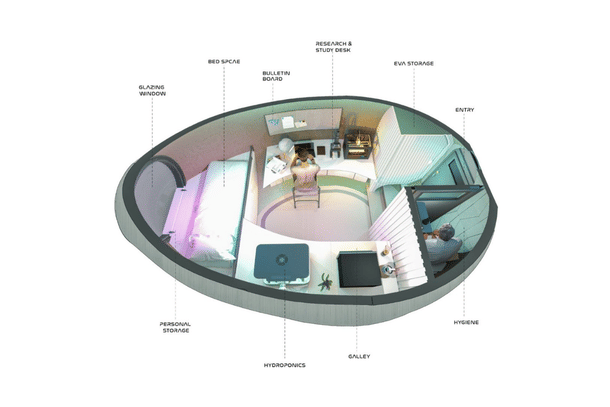

At the core of a space analogue is the habitat. The Ladakh Analogue Space Habitat (LASH), developed by space architecture company Aaka Space Studio, is a self-sustainable structure built for extreme environments.

“We had to set up a whole simulation where we feel like we were on Mars or in space and this (the extreme environment) is what we have to survive with,” says Aastha Kacha Jhala, the founder of Aaka Space Studio, based in Ahmedabad, Gujarat.

The 21-day duration of the expedition was intentional. According to Aastha, “It takes 21 days to build a habitat and nine days to build a lifestyle.”

An analogue astronaut inhabited the space for the duration of the expedition.

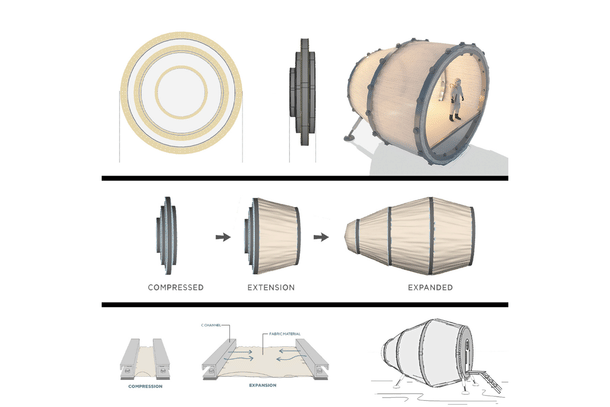

LASH operated on a combination of fuel and solar energy and featured an inflatable structure made of space-grade Teflon fabric. It was equipped with:

A dry hygiene compartment for sanitation needs

A hydroponic system to grow food like spinach and parsley

A 3D printer for manufacturing tools like hammers and scoops for geosampling

Sleeping quarters, storage spaces, and a laboratory for scientific experiments

A life support system

“We were understanding how much water supply we need, what kind of waste is coming out, how much oxygen levels are required, and we were also monitoring our analogue astronaut’s well-being with the help of biometric data collection,” Aastha said.

A major highlight of LASH is its circadian lighting system.

Unlike Earth, where we experience one sunrise and sunset per day, astronauts on the ISS witness 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets daily due to its 90-minute orbit around Earth. This irregular exposure to light disrupts the circadian rhythm — the body’s natural 24-hour cycle — leading to sleep disturbances and reduced cognitive performance.

To counter this unusual scenario, Aaka’s lighting system mimicks Earth’s natural light cycles, helping astronauts maintain a stable circadian rhythm and ensuring optimal mental well-being and performance.

Another standout feature of LASH is its deployable inflatable design. Unlike rigid habitats, inflatable structures offer efficiency in mass and volume, significantly reducing costs.

At the 53rd International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES) in July 2024, Aastha and her team even proposed using inflatable habitats for India’s future Bharatiya Antariksh Station.

“We want to build a prototype of our inflatable habitat and send it to space in the coming years. So, this (Ladakh experiment) was a preliminary study to design our inflatable habitat for space,” says Aastha, who says the habitat can be assembled in only a day’s time.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Space is hard, as the popular refrain goes. It holds true even for a simulation of space on Earth.

The leap from conceptual design to execution was enormous for Aaka Space Studio. The company had to contend with challenges of finding an isolated location, obtaining government permits, transporting materials, and managing logistics.

It proved to be a tough three weeks for the analogue astronaut too. “Our analogue astronaut’s well-being was very much challenged. For 21 days, he had to do repetitive tasks, like taking his biometrics, his oxygen supply, his BP (blood pressure), his heart rate, his blood glucose — everything was calculated and monitored, and he had to do a lot of reporting also,” Aastha said.

It didn’t help that he was cut off from everyone; no communication was permitted with the outside world. He was under 24-hour surveillance, with only a mission control team checking in on him, mainly to see if his vitals were alright.

Thankfully, his struggle was for a higher purpose. How the analogue astronaut coped physically and mentally in the extreme environment was a part of the mission’s learnings.

Not just the astronaut; even the space studio was tested on the job. At one point, the structural integrity of the habitat was compromised. “When the analogue astronaut went out of the habitat and then came inside, he had some dust on his shoes. So the habitat got contaminated with dust. We cannot really afford to do that with the Moon habitat. Because there is silica, and silica can damage the electrical systems,” Aastha says.

Lunar dust had kicked up trouble — and taken them by surprise! — in all of the six Apollo Moon landing missions of the United States (US).

A 2005 study by James R Gaier of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) said, "The severity of the dust problems were consistently underestimated by ground tests, indicating a need to develop better simulation facilities and procedures."

"The global lesson is clear," said the study. "More attention must be paid to the mitigation of the effects of lunar dust if EVA (extravehicular activity) elements are to last..."

When Aaka Space Studio encountered the dust issue in Ladakh, they swung into action — they designed a dust mitigation system just over the short course of the expedition.

The team has documented its findings in a report expected to be released in February 2025.

Why Ladakh

Tourists who have been to Ladakh woud easily testify to the otherworldliness of the place. From the ground beneath the feet to the air swirling over the heads, the Ladakh experience is so foreign that it’s... alien.

It was pleasing, therefore, to see scientists back us tourists up by giving their seal of approval to Ladakh’s otherworldliness.

There is even a place in Ladakh called “Moonland,” more properly called Lamayuru. This writer visited the enchanting moonscape 115 km from Leh in October 2023 to satisfy his twin loves of science (astronomy in particular) and Buddhism — Lamayuru also hosts a sacred eleventh-century Buddhist monastery. “Yuru Gompa” is the oldest monastery of Ladakh and preserves the cave where Mahasiddha Naropa (1016-1100) once sat in strict retreat.

Back to the science. Though scientists had previously marked out Ladakh as a potential space analogue site, its recognition by Dr Aloke Kumar, Associate Professor at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), shone a light on the subject last year.

“I had become interested in extraterrestrial habitation for quite some time,” says Professor Kumar, who co-authored a paper pitching for Ladakh as a space analogue site.

“As you know, our lab pioneered the idea of space bricks, where we took Martian and lunar simulant sands and made brick units out of them. We were looking into different technologies that could make these bricks. That was the beginning of my work (in this area),” he said.

Space bricks were a great research idea, but Kumar was thinking of ways to expand on it: building bigger extraterrestrial habitats was one way to proceed.

As Kumar began developing the idea, an unlikely visitor in Gaganyatri Shubhanshu Shukla enrolled in a Master’s program at IISc. Kumar and Shukla met up and began discussing science, and particularly space science, at great length.

Amidst all the science and technology chatter, with ideas orbiting around each other like binary stars, the need for space analogues sprung up in their conversations.

“During the Covid times, there was a lot of time, so we would sit and discuss how we could make habitats, what should be the future of the human race, and so on. During these discussions, we realised that there is a need for an analogue habitat on Earth,” Kumar said.

As spacefaring nations had already set up their own space analogues, Kumar and Shukla learnt that it was India that needed to get one — and subsequently more.

Further research led Kumar to the work of scientist — and Ladakh expert — Dr Binita Phartiyal of the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), Lucknow. The two of them discussed Ladakh’s potential as a space analogue and felt optimistic about its chances.

Kumar, Shukla, and Phartiyal — an engineer, an astronaut, and a geologist — then wrote up a paper (preprint) pitching for Ladakh as a site for setting up extraterrestrial analogue habitats.

They made their case clearly: “Our observations show that the Ladakh sector of the Trans-Himalayan region in India is one of the best sites for developing an analogue research station.”

“It is a dry, cold, arid desert, has abundant rocky ground, loose rock blanketing the mountain slopes, vast flat land, segregated ground ice/permafrost, rock glaciers, dunes, drainage networks, and catastrophic flooding and even dust devils making it geomorphologically similar to an early Mars and Moon,” they said in the paper.

Ladakh’s volcanic rocks, serpentinite exposures, saline lakes, and active hydrothermal systems provide clues about the chemical and geological processes that may have shaped the Martian surface.

The region’s permafrost hints at the presence of water in the past, while its high ultraviolet and cosmic radiation levels, low atmospheric pressure, and boron-rich hot springs create an environment that mimics Martian conditions.

Additionally, Ladakh’s vast, barren landscapes and igneous rock formations closely resemble the Moon’s surface, making it an excellent testing ground for lunar research as well.

Ladakh, thus, became a natural and firm favourite, at least to kick off India’s space analogues journey.

“Once the paper was published, Aastha reached out to us, and she was already doing something in Gujarat, in Rann of Kutch, by herself. She was very enthused with our paper. We put forward more of a policy, that somebody should do it, and then she went ahead and did it, and it was fantastic,” Kumar said.

Breaking New Ground

What Aastha was doing “in Gujarat, in Rann of Kutch, by herself” was laying the foundation for India’s very first space analogues.

Her engagement with analogues began in Canada, where she initially set up and ran Aaka Space Studio for about a year and a half.

At that time, she worked closely with the Mars Society of Canada and managed an analogue research station for them, called “FMARS,” located on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic.

However, after marriage came calling, Aastha moved back to India. “And then I was, like, India is the only country (among the spacefaring nations) which does not have analogues. And if we are planning to send astronauts to space in the coming future, there must be an awareness of how an astronaut’s life looks like,” she said.

Although Ladakh was on her mind, Aastha zeroed in on the Rann of Kutch as the site of her first analogue expeditions in India. “The Rann of Kutch is a scientific analogue site because it has Jarosite. Jarosite is also available on Mars,” says Aastha, adding that “during winter times, the white Rann” also resembles “the Moon’s landscape.”

Receiving special permission from the Border Security Force (BSF), Aastha and her team started living in the white sands of Dholavira in complete isolation and without access to essential public utilities like power supply.

Interestingly, the region carried extraordinary significance beyond space science. “We had this fossil park there, which had fossils from the time of the dinosaurs. And it also had the Harappan civilisation, the ancient civilisation of the world. So the idea was that, to design the first civilisation or first habitat on the Moon, we need to study the first civilisation or first habitation on Earth. That’s why we chose this site,” Aastha explains.

She led five space analogue missions — sometimes featuring all-women teams — in the Rann of Kutch before shifting base to Ladakh for the space analogue mission that had heavy hitters like ISRO’s Human Space Flight Centre, the University of Ladakh, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay, and the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council participating and even got a lot of people talking.

Looking ahead, Aastha is in talks with the University of Adelaide, Australia, to set up a permanent analogue facility in India. The plan is for multiple crew members to be stationed at this facility in an undisclosed location for varying intervals as part of astronaut training and research and development towards advancing space habitation.

The Road to India's Human Space Missions

India’s human space programme is accelerating. With Gaganyaan set to launch in 2026 and plans for a national space station and a Moon landing in the next decade, space analogues will be critical in preparing astronauts and testing habitat technologies.

“The Bharatiya Antariksh Station, and even the Indian on the Moon, will be a gigantic step for India because the way our current space programme is set up, it is with Vikram Sarabha’s vision of mostly satellites, and so on. Now ISRO is changing its direction in some ways. That change is not going to be easy. And for that, it needs to reach certain landmarks. This analogue habitat will be one of them,” Prof Kumar says.

“It’s not the only one,” he is quick to clarify, “but it has to be one of the absolute landmarks that is required for a successful human space programme.”

All major spacefaring nations — the United States, Europe, Russia, and others — have operational space analogues. These facilities help study isolation effects, test engineering solutions, and prepare astronauts for real missions.

“These habitats are essential for understanding, say, the effect of isolation on humans. So you put an astronaut in for six months. What happens? You can supply them food, but you cut them off from the rest of human communication. What happens then? And you put them into an extreme environment where there are sudden accidents or changes. How do humans respond to that? Plus what is the engineering that will go into it? So many things it (a space analogue) helps us understand. So it is critical,” Prof Kumar says.

India’s foray into this crucial space (no pun intended), therefore, marks a crucial step in its space exploration journey. In addition to Ladakh and the Rann of Kutch, India can explore the potential of the Lonar, Dhala, and Ramgarh craters, the caves of Meghalaya, and the volcanic terrain of the Barren Islands, among others, to serve as Martian analogue sites.

As ISRO marches towards a future of human space habitation, it can count on space analogues to learn new science, refine technologies, prepare astronauts for the challenges of living beyond Earth, and, when the time comes, ensure mission success.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.