Science

Young Chennai Startup Develops Cutting-Edge Radar Imaging Technology Tailored To India's Needs

Karan Kamble

Oct 15, 2021, 03:25 PM | Updated 03:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought most of the world to a standstill. The wheels of industry that turned day after day, year upon year, seemed to grind to a halt all of a sudden last year.

Yet, during this time, some Indian innovators rose up against the challenge and strengthened their resolve to innovate.

Born out of the pandemic is one such effort by two engineers based in Chennai who are passionate about technology, in general, and electronics, software, and imaging, in particular.

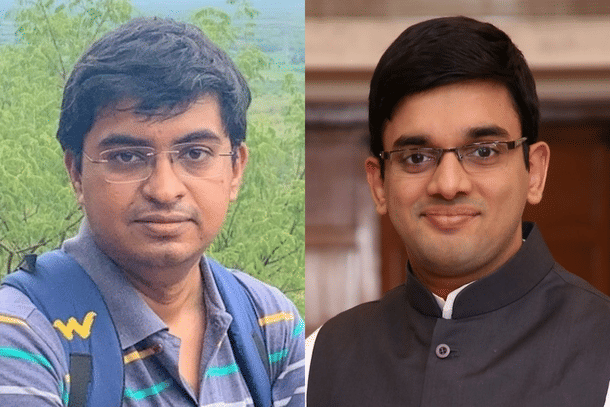

Shashwath T R and Sharan Srinivas J used their time in the pandemic to develop cutting-edge radar imaging technology that potentially has applications ranging from underground to space, with wider implications for public safety, while being well-suited to India’s needs.

The pioneering work is taking off under the business venture Mindgrove Technologies Private Limited. Mindgrove was formed in early 2021 by Shashwath and Sharan.

While Shashwath wears the hat of a chief executive officer, Sharan essays the role of chief technology officer. Armed with ambition, they are building various types of radars and imaging systems that have use in both civilian and military sectors.

Mindgrove is currently incubated at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras–hosted Section 8 company Pravartak Technologies Foundation (PTF), which is a Technology Innovation Hub for sensors, networking, actuators, and control systems.

The Making Of Mindgrove

Shashwath and Sharan were colleagues at Lucid Software Limited, where they worked on “non-destructive testing” or NDT. This refers to the testing of material without breaking it apart.

“An example for the human body might be using an X-ray to look into your bones without cutting apart the body to see where the bones are,” Shashwath tells Swarajya.

Lucid was the world’s only software solutions provider for NDT. According to Shashwath, the world of NDT had been left behind in the analog space for far too long, and he and his colleagues were working to bring the technology into the digital age.

For example, they were trying to level up the automation in ultrasound technology so that specialists could view readable digital images of the human body rather than try to decipher squiggly lines plotted on graphs.

While this was fruitful work, Shashwath wanted to run more than just the software end of the show. He says he “started getting irritated working with somebody else’s hardware”. A lot of the struggles had to do with having to import hardware.

Import restrictions and export controls often affected their project work because it demanded additional effort well out of their way, causing timelines to stretch out unreasonably.

Besides, as an electronics engineer, Shashwath knew how to work the hardware too. So, he began to play with the idea of developing an all-in-one hardware-software imaging solutions venture that would serve Indian needs.

He explored this direction while building up his technological muscle over many years. Along the way, he found a collaborator in Sharan, who had joined Lucid in 2016 and displayed similar interests.

Sharan brought a complementary skill set to the table. “Shashwath is naturally more creative while I am naturally more systematic. Real-world experience has since trained us to be creative and systematic respectively. Over the years, that particular skill combination has allowed us to hold each other up and bring out innovative solutions as a team,” he says.

Sharan had picked up an undergraduate degree in computer science from Chennai-based Meenakshi Sundararajan Engineering College before proceeding to ETH Zürich in Switzerland — famous as the institute where Albert Einstein received his education and later taught — to study computational science. Right after, he joined Shashwath at Lucid.

They began to put their heads together. “We kept talking about how to build hardware and high-performance computing and related things,” Shashwath says.

Sharan enrolled into a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) programme at IIT Madras. His thesis adviser is Professor Veezhinathan Kamakoti, who leads the efforts of the Reconfigurable Intelligent Systems Engineering (RISE) group at IIT Madras to build the indigenous open-source Shakti processor ecosystem.

“And then the pandemic hit and I hadn’t seen the inside of an office since March 2020,” Shashwath tells me.

Sharan adds: “I had spent the calendar year 2019 shuttling between IIT-M for coursework and Lucid for product development work literally every working day. Then spent all day during the weekends catching up on assignments. I had just completed my comprehensive examinations at IIT-M when the first lockdown hit.”

In an instant, Sharan went from “being a total workaholic to nearly idle”. He says, “It was nice to catch up on some sleep initially. And while there were still deliveries to be made in an official capacity, this was still the uncharted waters of the first wave and workload was low and slow. I then began to talk to Shashwath about the possibility of doing something."

By the end of the year, Shashwath and Sharan got started on Mindgrove.

When an opportunity came knocking from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology to make good use of the Shakti microprocessor, through the Swadeshi Microprocessor Challenge, Shashwath and Sharan decided to have a crack at it.

“We thought of everything from a baby monitor up,” Shashwath says. “Because I had a child, I thought, ‘Okay, a baby monitor is something I would definitely buy’.”

They also thought of building secure communication systems, but soon enough, Shashwath knew which path he had to take. “My entire focus in my career had been imaging — industrial imaging, image processing, signal processing. So I wanted to do something along those lines, do something which I know,” he says.

“I adore learning and I am always up for an engineering challenge. The 2010s was a decade where I explored domains ranging from neuroscience to additive manufacturing while naturally converging on vision and allied systems. I was quite happy to follow along,” Sharan adds.

After zeroing in on imaging, and taking good stock of their capabilities and limitations imposed by the pandemic, the Shashwath-Sharan duo took off on building a ground penetrating radar.

Ground Penetrating Radar

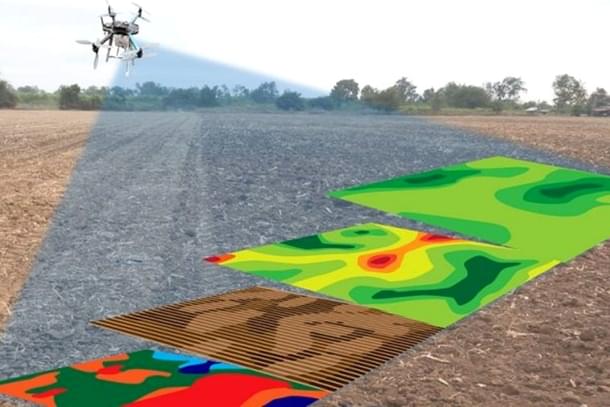

A ground penetrating radar or GPR is a tool primarily used for inspection and mapping in the infrastructure space. Roads, buildings, and bridges can be scanned quickly and cost-effectively using GPR so that the “health” of the structure can be ascertained.

An early look, courtesy the GPR, allows for faster decision making that can improve, among various things, public safety.

Shashwath wasn’t new to GPR. It was a technology he had engaged with in 2011. The project back then had involved scanning concrete via multiple platforms like ultrasound and GPR so that the inside of the concrete could be imaged. It would reveal details such as the presence of a crack and changes in the density of concrete.

Impressed by the technology, he had sought to keep up with GPR and, over time, picked up some of the essential know-how. He realised it was a better alternative to ultrasound — a tool he used predominantly over the years — because of the challenges with procuring and working with the latter.

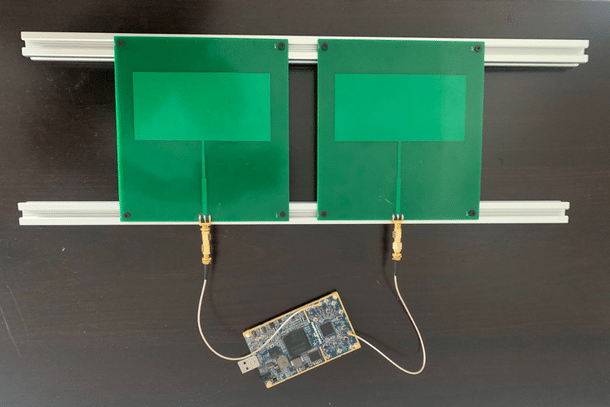

“A radar doesn’t require so much of that stuff (compared to ultrasound). All it needs is a radio transmitter and a receiver of the correct frequency and a few other components like an antenna,” Shashwath says.

Sharan explains: “In my ETH days, I experienced first-hand how seemingly tiny optimisations in software can add up to huge performance improvements at scale. So when done right, I knew that a good portion of computations done today, for example, in the cloud, can be done on the system right then and there. This is known in the industry today as ‘edge computing’. So the idea was to take the radio signal and write the software to process said signal right there, on the Shakti processor."

And thus, it came to be — Mindgrove would work with GPR.

They began the groundwork for the technology in 2020, kicked off official operations in March this year, and are now very close to a prototype.

Shashwath and Sharan have done much of the heavy lifting during this period, with useful help coming from project interns — picked from the Master of Technology (MTech) programme at IIT Madras — who are working on components that will be integrated into the GPR.

Even as Mindgrove is getting the GPR ready, they have their eyes set on extended applications. “From GPR, we plan to move to other forms of radar, such as the millimetre-wave radar, which is used in the automotive industry,” Shashwath tells me.

The situational awareness of autonomous vehicles such as that made by Tesla, for instance, interestingly comes from the radar they have on board.

The millimetre-wave radar provides position and velocity with reasonable accuracy. Therefore, Mindgrove’s frequency modulated continuous wave radar, which is still in the works, could be used to detect, say, unmanned aerial vehicles.

They are also planning radar applications using drones, which, Shashwath says, has strategic importance for India. “Right now all of these devices are being imported even though the drones can be made in India. The more we make these kinds of things within India, the more we can reduce the cost and actually turn a profit,” he says.

An important byproduct, of course, is greater self-reliance within the Indian industry.

Mindgrove’s radar uses new electronics that cost less while also being energy-efficient enough to be mounted on a drone so that a larger area can be scanned faster than before.

In addition, the GPR prototype can be extended to synthetic aperture radar (SAR) to serve purposes such as remote sensing. SAR uses a radar that is mounted on a moving platform to create 2D or 3D images of a target.

SAR is, in fact, the basis for a NASA-ISRO Earth-observing space mission that is proposed to be launched by India in early 2023.

The joint satellite mission will use radar to take a good, close look at many Earth processes — earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides, sea ice and glacier movement, among others — over all the land masses, including the polar cryosphere and the Indian Ocean region.

Such impressive applications are a possibility for Mindgrove in the future.

Applications, Near And Far

Mindgrove’s prototype design makes it immediately ideal for scanning concrete or a brick wall.

Say, if there is a persistent leak in a building, the use of the GPR can help avoid the physical manipulation of the structure merely to diagnose the problem.

“GPR is highly sensitive to changes in moisture, so instead of trying to rip up apart the structure, you can have a way of figuring out which section of the slab might be affected,” Shashwath says.

Beyond direct consumer application, the GPR can be used in civil infrastructure. Metro rail is one example — GPR, in this case, can be put to work for periodic inspection of the many pillars that dot the rail routes.

“If we can build it in such a way that it is easy to use and you will just run it over the column every few months, it can tell you whether there is, say, a crack developing so that advance action can be taken and loss of human life and property can be avoided,” Shashwath says.

This use case can be naturally extended to roads, flyovers, bridges, dams, and other commonly used civil infrastructure. Municipal corporations can locate and map underground pipes and cables to keep power and water operations running smoothly. Even archaeologists would benefit from this technology.

As Shashwath describes it, it can be used “basically for anything underground".

The GPR technology hasn’t already been used for civil infrastructure purposes in India because it is a costly exercise and the resulting images aren’t easy to read unless a specialist takes a look at them.

“The market wishes for a tool which gets the job done correctly and rapidly. Ease of data inference, if absent, effectively kills adoption," Sharan says.

This is why, besides reducing the cost, Mindgrove is working to make image interpretation easier. “For example, we might use augmented reality. Put on a pair of virtual reality goggles and you’ll see the column you’re inspecting and it highlights where it thinks there is a crack,” Shashwath says.

But he also adds a caveat: it remains to be seen whether this is possible and if the market really wants this feature.

Meanwhile, Mindgrove was recently among five startups handpicked by IIT Madras’ Pravartak Technologies Foundation to collaborate in the area of space technology.

According to IIT Madras, the consortium, named Indian Space Technologies and Applications Design Bureau (I-STAC.DB), will work to develop and commercialise technologies related to space and deep space with a focus on next-generation applications.

They intend to build an “end-to-end aatmanirbhar” or self-reliant space-tech ecosystem.

Among the areas of focus listed by IIT Madras are space vehicles, rapid launch capability, satellite design and assembly as well as safety, next-generation communication technology like 6G, ground station infrastructure, and space debris management.

Shashwath explains that the challenge with the space segment is that the volumes are very low and the initial investment is very high. Rigorous testing of devices and components before they are shipped to space can also take a toll on a startup.

Additionally, Mindgrove would have to redesign their device for parameters like power requirements, since penetrating a four-inch wall is very different from being shot up 400 km into space.

That said, Shashwath says the sensor developed by Mindgrove is versatile and can be integrated, if need be, into a phone held in hand or a satellite flying in space.

Further, despite any uncertainty of application in the space-tech segment, Shashwath is keen to impact the space domain using his technology.

“I mean, my mother is a geography teacher too, so GIS is a field which I love a lot. Personally, it would be very rewarding for me to work with GIS, in remote sensing and other areas. The moment we see a business case, I will jump on it,” he says.

Next Steps

For now, Mindgrove is focused more on down-to-earth applications. They say they are currently looking to address three segments of the market in the immediate future — governmental or big infrastructure sector, defence sector, and non-governmental sector.

Whereas metro rail, airport runways, and power plants count as potential use cases in the civilian government sector, tunnel building and landmine detection are examples in the military sector.

“The concept here is that you add GPR to a drone, fly it over a piece of land, and figure out where there is a landmine. Or at least flag the areas where there may potentially be a landmine,” Shashwath says.

However, the civilian infrastructure space is likely to present the first opening for Mindgrove’s prototype. Shashwath and co will soon be taking their prototype to interested parties, some of whom they are already in talks with, and identify the requirements that they can meet on their radar.

After they accomplish initial sales locally, they plan to take their offering abroad. “The growth market for the GPR technology is no longer the West, it is going to be Asia,” Shashwath says, citing the Middle Eastern and South East Asian regions in particular as potential markets.

The realm of possibilities for Mindgrove is wide and impressive in this nascent stage. But for now, Shashwath and Sharan are staying grounded and taking it one step at a time, aiming at grounded success before they can spread their wings to fly.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.