Society

In Immigration-Obsessed Punjab, IELTS Coaching Is Part Of State School Curriculum And Could Be Introduced In Colleges

Swati Goel Sharma

Nov 07, 2023, 02:15 PM | Updated 03:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Unlike many of his peers still uncertain about their futures, Chetan has mapped out a clear path for himself: he would complete a diploma in hotel management from Delhi, aided by the support of his paternal uncle who lives in the national capital city.

He would then migrate to Canada and work as a chef in a Punjabi-owned restaurant.

His inspiration, intriguingly, comes from Punjabi films.

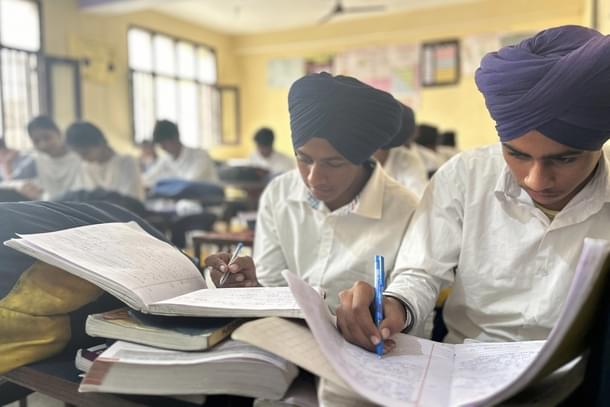

Chetan, who uses only the first name, is a student of Class 11 at a Punjabi-medium government school in Ayali Khurd village of Ludhiana district, where he has opted for Humanities.

His teacher says he is the best in class in mehendi application, a skill he honed in his Beauty and Wellness subject, designed as a vocational course to enable students to work in salons.

Chetan's aspirations involve a formidable challenge, a linguistic barrier that he must cross — proficiency in English.

At present, he cannot articulate in English why he wants to become a chef or work in Canada, but he is determined to master the language. The class he most looks forward to in school is the Interactive English Language Training for Students or ‘IELTS’.

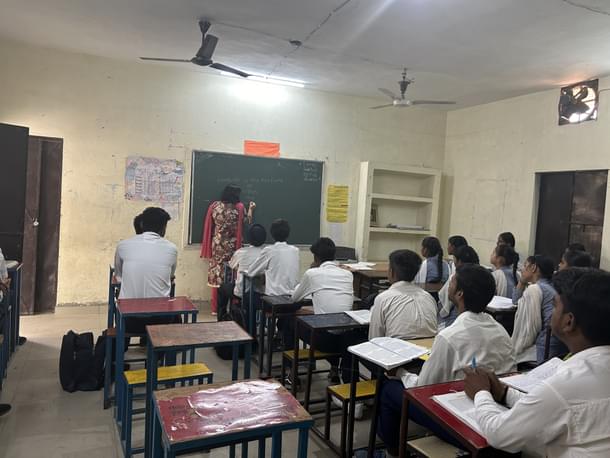

The school’s IELTS module, an acronym playfully echoing the globally recognised International English Language Testing System that is a pre-requisite for entry into more than 140 countries, is a Punjab government endeavour aimed at bolstering English skills for Class 11 and 12 students in state-run schools.

The weekly classes use audio-visual tools to enhance English language skills across listening, reading, writing and speaking, collectively known in language-testing circles as ‘LRWS’.

The curriculum emphasises practical communication, teaching students to introduce themselves, speak on a given topic, and express their thoughts coherently in English.

Performances are assessed on a 9-band scale, mimicking the global IELTS certification that is jointly managed by the British Council, Australia-based IDP Education Pty Limited and Cambridge Assessment.

Chetan says the school module primes him for the actual test, for which he would later take private coaching if required.

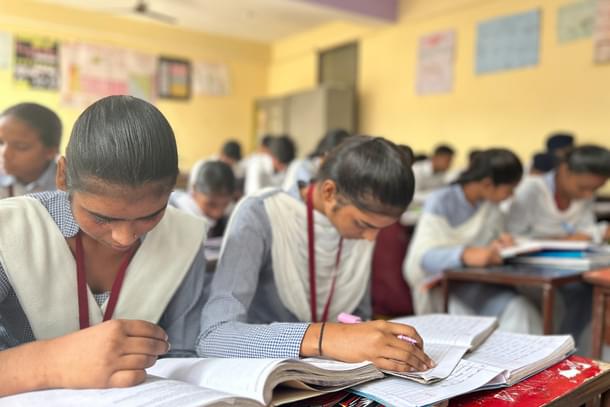

Gurleen Kaur, a Commerce student at the same school, similarly finds the classes beneficial if not sufficient. Her cousin migrated to UK on a study visa last year, and she plans to follow her footsteps.

On her cousin’s advice, she has additionally started using a social media app to refine her English, where she directly engages with UK nationals.

Chetan and Gurleen are not alone in their foreign aspirations. The allure of moving abroad, particularly to countries like Canada, Australia, the UK and the US, resonates deeply among Punjabis.

Between 2016 and February 2021, 4.78 lakh people from Punjab left the country for employment and another 2.62 lakh for studies, according to a Lok Sabha reply by V Muraleedharan, Minister of State for External Affairs.

Canada remains a preferred destination. In the first six months of 2023, around 1.75 lakh students received visas, according to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada.

The fervour for foreign education and employment has transformed IELTS coaching into a thriving industry in the state. As many as 20,000 such centres are currently operating in Punjab, providing coaching and facilitating the test-taking.

While the cost of the test is about Rs 16,000 per student, coaching charges per month vary from Rs 6,000 to Rs 20,000 per month per student. Nearly six lakh students from Punjab take the English proficiency tests annually.

The financial burden of such coaching, alongside the test costs, presents a significant challenge for many aspiring students. Political parties have time and again sold subsidised IELTS coaching as a poll promise or a welfare scheme.

In the run-up to the 2022 Assembly elections, eventually won by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), the Shiromani Akali Dal promised interest-free loans of up to Rs 10 lakh for students, covering not only college fees but also IELTS coaching.

Prior to their electoral defeat, the Congress-led Punjab government formalised a Memorandum of Understanding with the University of Cambridge Press India to extend IELTS coaching to students in government-run Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) and polytechnic colleges.

This May, Punjab's NRI Affairs Minister from the AAP, Kuldeep Dhaliwal, recommended incorporating the IELTS into the curriculum of state-run colleges.

In state-run schools, the ‘IELTS module’ was launched five years ago under the then Congress government, and has persevered even under the new Aam Aadmi Party regime, albeit with a revised name — Intensive English Language Teaching System, retaining the familiar acronym.

The launch wasn't without criticism. Though started with a stated aim to mitigate the financial burden on students, it triggered a backlash for encouraging youth migration.

The project was temporarily renamed as 'Communication Skills', but was named IELTS again as it failed to attract students.

Today, the IELTS module is being taught on several platforms of the state education department, such as EDUSAT, PM e-Vidya YouTube channel, listening labs in schools and Punjab Educare mobile app.

At the Ayali Khurd school that this correspondent visited, which caters predominantly to children from financially modest backgrounds, including those from 'lower' castes and domestic migrant families, the dream of foreign education remains daunting due to both linguistic and financial barriers.

For many, the hefty cost of migration, ranging from 15 to 30 lakh rupees, renders this dream seemingly unattainable.

As per an analysis, each Punjabi student in Canada pays around 17,000 Canadian dollars in annual fees, in addition to depositing 10,200 Canadian dollars as Guaranteed Investment Certificate (GIC) funds, with students from Punjab overall spending a staggering Rs 68,000 crore in Canada annually.

Chhaya’s grandfather migrated from Uttar Pradesh’s Ahmedgarh to Punjab, where he took up work as a farm labourer. This step marked the family's first stride towards a better life. Then, Chhaya's father further uplifted the family's financial status by securing employment in a laboratory at the Punjab Agricultural University in Ludhiana.

The family's progress took a significant leap when Chhaya's maternal aunt, merely a few years older than her, ventured to Canada last year.

This move was made possible through the unified contributions of the entire clan. They rallied together, pooling funds for her aunt's preparatory coaching, followed by the expenses for her studies and living abroad.

In Canada, the aunt is expected to not just send remittances back to support the family in Punjab, but also act as a bridge to the future, potentially facilitating the immigration of other family members.

Meanwhile, Chhaya, a student in the Humanities, has resolved to pursue a career in nursing within India, knowing very well the financial constraints in her own foreign dreams.

Amid these stories of aspiration and challenge, Principal Kanwaljeet Kaur highlights the broader benefits of the IELTS course, emphasising its role in enhancing English skills, a critical factor for success both internationally and domestically.

Her observation seems pertinent as Punjabi speakers have historically scored lower on average in IELTS testing.

Punjabi-speakers were found to have scored the lowest among the Indian regional languages in the test, as per figures made public by IELTS of the mean scores of students based on their first-language background in a recent survey. The average band score, calculated as average of band scores for LRWS, of a Punjabi test-taker was 5.8.

Husnmeet Singh, from the Science stream, says he benefits from the IELTS module but is resolved to stay in India. He draws insights from a Facebook group where Punjabi expatriates share their life experiences abroad.

In this online community, Husnmeet has observed a predominance of challenging stories over rosy ones. He says the accounts have been eye-opening, particularly in highlighting the limited options available to those who migrate immediately after completing Class 12 without specialised skills.

He has learned that the most lucrative role for such individuals is truck driving, and less desirable alternatives include labor-intensive construction work or night shifts in a sandwich shop.

The concept of an economic "recession" is another critical insight Husnmeet has gleaned from these interactions, a term frequently mentioned by expatriates discussing the fluctuating job market and economic stability overseas.

These revelations have steered Husnmeet towards a decision to pursue engineering in India.

Alongside his technical education, he aims to refine his English proficiency, not as a stepping stone to foreign shores, but as a tool to enhance his professional prospects within his homeland.

Swati Goel Sharma is a senior editor at Swarajya. She tweets at @swati_gs.