World

The Sorry Tale Of Cuban Communism

Daniel J. Mitchell

Sep 06, 2016, 11:25 AM | Updated 11:24 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Communism should be remembered first and foremost for the death, brutality, and repression that occurred whenever that evil system was imposed upon a nation.

Dictators like Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, the North Korean Kim dynasty either killed more than Hitler, or butchered higher proportions of their populations.

But let’s not forget that communism also has an awful economic legacy. The economic breakdown of the Soviet Empire. The horrid deprivation in North Korea. The giant gap that existed between West Germany and East Germany. The mass poverty in China before partial liberalisation.

Today, let’s focus on how communism has severely crippled the Cuban economy.

In a column for Reason, a few years ago, Steven Chapman accurately summarised the problems in that long-suffering nation.

“There may yet be admirers of Cuban communism in certain precincts of Berkeley or Cambridge, but it’s hard to find them in Havana. The average Cuban makes only about $20 a month— which is a bit spartan even if you add in free housing, food, and medical care. For that matter, the free stuff is not so easy to come by. Food shortages are frequent, the stock of adequate housing has shrunk, and hospital patients often have to bring their own sheets, food, and even medical supplies. Roger Noriega, a researcher at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington, notes that before communism arrived, Cuba “was one of the most prosperous and egalitarian societies of the Americas.” His colleague Nicholas Eberstadt has documented that pre-Castro Cuba had a high rate of literacy and a life expectancy surpassing that in Spain, Greece, and Portugal. Instead of accelerating development, Castro has hindered it. In 1980, living standards in Chile were double those in Cuba. Thanks to bold free-market reforms implemented in Chile but not Cuba, the average Chilean’s income now appears to be four times higher than the average Cuban’s. In its latest annual report, Human Rights Watch says, “Cuba remains the one country in Latin America that represses virtually all forms of political dissent.”

The comparison between Chile and Cuba is especially apt since the pro-market reforms in the South American nation came after a coup against a Marxist government that severely weakened the Chilean economy.

Chapman points out that the standard leftist excuse for Cuban misery— the U.S. trade embargo— isn’t very legitimate.

“The regime prefers to blame any problems on the Yankee imperialists, who have enforced an economic embargo for decades. In fact, its effect on the Cuban economy is modest, since Cuba trades freely with the rest of the world.”

Since the U.S. accounts for nearly one-fourth of world economic output, I’m open to the hypothesis that the negative impact on Cuba is more than “modest.”

But it still would be just a partial explanation. Just remember that communist societies have always been economic basket cases even if they have unfettered ability to trade with all other nations.

Writing for the Huffington Post (hardly a pro-capitalism outfit), Terry Savage also explains that Cuba is an economic disaster.

“…the economic consequences of a 50-year, totalitarian, socialistic experiment in government are obvious today. Cuba is a beautiful country filled with many friendly people, who have lived in poverty and deprivation for decades. Socialism in its purest form simply didn’t work there. I was immediately reminded of that old saying: “Capitalism is the unequal distribution of wealth – but socialism is the equal distribution of poverty.” Once-magnificent buildings are literally crumbling, plaster falling and walls and stairways falling apart, as there are no ownership incentives to maintain them – or profit potential to incent their preservation. Every Cuban gets a ration book and an assigned “bodega” in which to purchase the low-cost, subsidised food. The one I visited looked like an empty warehouse, with little on the shelves. If the rice, beans, eggs, and cooking oil are not in stock, the shopper must return the following week. Allowed five eggs per month, the basics barely cover a starvation existence. The economic results of their 50-year rule have been abysmal. Cuba became a protectorate of the old Soviet Union (remember the Cuban missile crisis) -and that worked until the early 1990s, when the USSR fell apart. No longer receiving aid from its protector, Cuba entered a long period now remembered as “the special times” when Cubans were literally starving, when there was electricity only two hours per day, and people turned any patch of dirt into a garden to survive. Cubans bear the scars of that terrible time, and for many the current situation is still not that much better.”

So Cuba was a basket case that was subsidised by the Soviet Union. When the Evil Empire collapsed and the subsidies ended, the basket case became a hellhole.

The good news, if we’re grading on a curve, is that Cuba has now improved to again being a basket case.

But that improvement still leaves Cuba with a lot of room for improvement. It may not be at the level of North Korea, but it’s worse than Venezuela, and that’s saying something.

My friend Michel Kelly-Gagnon, of the Montreal Economic Institute, echoes the horrid news about Cuba’s economy.

“As anyone who has spent any amount of time in Cuba outside the tourist compounds can tell you, socialism, particularly the unsubsidised version that we have seen since the fall of the Soviet empire, has been a disaster. The hospitals which supposedly offer free care only do so quickly and effectively to the politically connected, friends and family of staff members, and to those who pay the largest bribes. That “free” university education that many Cubans get in technical fields is rarely worth much more than what students pay for it. There are few books in the country’s schools, and those that can be found are years, if not decades old. The country’s libraries are empty. The guaranteed jobs that all Cubans have are fine, until you realise that the average salary is in the range of $20 a month. Worse, the food and other staple allotments that Cubans have long felt entitled to, have shrunk over the years. Tourists often marvel at how thin and healthy Cubans look. Sadly, many of them are outright hungry.”

Though Michel includes a bit of optimism in his column, pointing out that there’s been a modest bit of economic liberalisation (a point that I’ve also made, even to the point of joking about whether we should trade Obama for Castro).

“Communist Cuba, beset with an oppressive bureaucracy, an anachronistic cradle-to-grave welfare state, a hopelessly subpar economy, and widespread poverty, is gradually shifting to private sector solutions. Starting when Raul Castro “temporarily” took over power from his brother Fidel six years ago and culminating with the Communist party’s approval of a major package of reforms, Cuba has taken a series of increasingly bold steps to implement free market reforms. These range from providing entrepreneurs with increased flexibility to run small businesses, and use of state agricultural lands by individual farmers, to the elimination of a variety of burdensome rules and regulations. Ironically, there is a lot that Canadians can learn from that shift.”

And there’s a lot the United States can learn, particularly our President, who is so deluded that he said there are (presumably positive) things America can learn from Cuba.

One common talking point from Cuban sympathisers is that the country has done a good job of reducing infant mortality. But, as Johan Norberg explains, that claim largely evaporates upon closer examination.

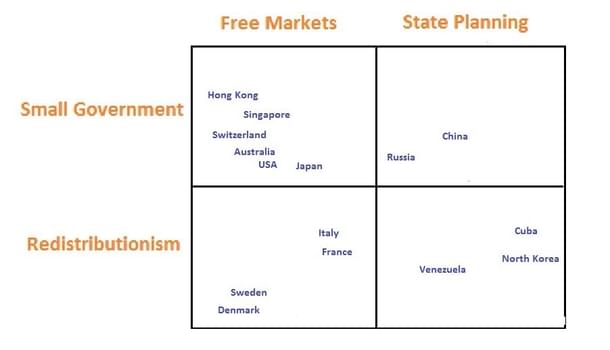

The bottom line is that communism is a system that is grossly inconsistent with both human freedom and economic liberty.

And because it squashes economic liberty (thanks to central planning, price controls, and the various other features of total statism), that ensures mass poverty.

Amazingly, there are still some leftists who want us to believe that communism would work if “good people” were in charge. I guess they don’t understand that good people, by definition, don’t want to control the lives of others.

This piece was originally published on the author’s personal blog and has been republished here with permission.

Daniel J. Mitchell is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, Washington’s premier free-market think tank.