World

Tyranny Of Blasphemy Laws In Pakistan Only Underscores Need For CAA In India

Arshia Malik

Sep 23, 2023, 04:31 PM | Updated 04:31 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Pakistan, a country with a predominantly Muslim majority, has been grappling with a contentious issue that intersects religion, politics, and human rights—blasphemy laws.

Rooted in colonial history, these laws have evolved into a tool that is often misused to target religious minorities and stifle dissent.

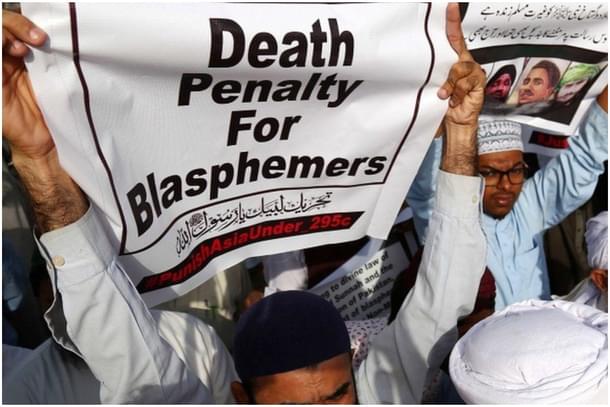

Recently, in Jaranwala, Pakistan, thousands of Muslims burned churches and vandalized homes of Christians. The violence was triggered by claims that two Christian men had torn pages from the Quran. The incident led to mobs attacking Christian homes and looting, as well as the burning of 18 churches. The accused Christian men have been charged with blasphemy, punishable by death in Pakistan.

Blasphemy allegations in Pakistan often result in widespread riots and violence. Earlier, a Christian couple was burnt alive on such allegations, and there is of course the infamous case of Asia Bibi, who was defended by Salman Taseer.

Taseer was later assassinated by his own bodyguard for defending a Christian woman in court. The Pakistan police were criticized for not intervening to stop the protestors, and they explained to reporters that they aimed to avoid escalating the situation.

The recent violence on the Christian community sparked protests by the community in various Pakistani cities. The involvement of an Islamist political party, Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), was reported, but the TLP denied any connection. Pakistani leaders and international human rights groups condemned the violence.

The beginnings of blasphemy

The foundation of Pakistan's blasphemy laws dates to the British colonial era when these laws were introduced in British India to prevent religious tensions between communities. However, the laws have been far from unifying, and they have become increasingly controversial over time.

Post-Partition, in the 1980s, during the military rule of General Zia-ul-Haq, the laws were strengthened, including the introduction of the death penalty for blasphemy.

This move was aimed to appease conservative religious groups, who the Pakistani military establishment in their policy of Ghazwa-e-Hind wanted to nurture but it triggered unintended consequences—violence, discrimination, and the suppression of free expression.

Blasphemy accusations have become disturbingly common in Pakistan, and their consequences are severe. Even the mere accusation of insulting Islam or its figures can incite violent reactions from the public, including riots, lynchings, and killings.

The sensitivity surrounding blasphemy has created an environment where individuals are quick to take matters into their own hands, fuelled by a perceived duty to protect their religious beliefs. This climate of fear and intimidation disproportionately affects religious minorities, who are often the targets of accusations.

One alarming consequence of the misuse of blasphemy laws is the emergence of extremist and vigilante factions within Pakistan. These groups are willing to resort to violence to achieve their goals. Often backed by significant financial resources, they intensify the fragmentation of society by targeting minority groups and creating an atmosphere of fear and mistrust. The government's inability to effectively address these factions further contributes to the problem, allowing them to operate with impunity.

The situation in Pakistan highlights the intricate relationship between religion, politics, and human rights. The misuse of blasphemy laws, the rise of extremist factions, and the resulting violence against minorities underscore the dire need for reform. The government must revisit and revise the blasphemy laws to ensure they are not used to target minorities or suppress dissent.

It is for the benefit of such minorities in India’s neighbourhood that the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), was passed by the Indian government in December 2019.

The CAA provided a path to Indian citizenship for religious minority groups in neighbouring countries, namely Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians, who have faced religious persecution in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh and entered India before December 31, 2014. The primary objective of the CAA is to offer refuge to religious minorities who have faced discrimination and persecution in their home countries due to their faith.

The Indian government defended the CAA as a humanitarian gesture aimed at providing a haven for persecuted minorities. It was repeatedly clarified that the law did not affect the existing citizenship status of any Indian citizen and that it was in line with India's historic commitment to sheltering refugees fleeing religious persecution.

International human rights organizations have consistently condemned Pakistan's blasphemy laws, emphasizing their violation of freedom of speech and expression. However, a symmetrical appreciation for India’s efforts to provide refuge to the minorities who bear the brunt of these laws is missing.

The international community can play a crucial role in pressuring Pakistan to take concrete steps toward reform, urging the country to protect the rights of all its citizens, regardless of their religious beliefs. Given the delicate situation the Pakistan economy is in, the Pakistan state would also waste no time in at least fulfilling those demands which would qualify as ‘low-hanging fruits’.

However, all of that is assuming that the Pakistani government responds to the same incentives that any other government in the world would. With Pakistan, that assumption comes with risks.

Arshia Malik is a columnist and commentator on social issues with particular emphasis on Islam in the Indian subcontinent.