Ideas

Why This Constitution Drafting Panel Member’s Pitch For Uniform Civil Code Rings True Even Today

- The case for a uniform civil code has never been stronger than it is today.

- In a rapidly modernising world, where human rights are sacrosanct, all aspects of unequal laws must be discarded.

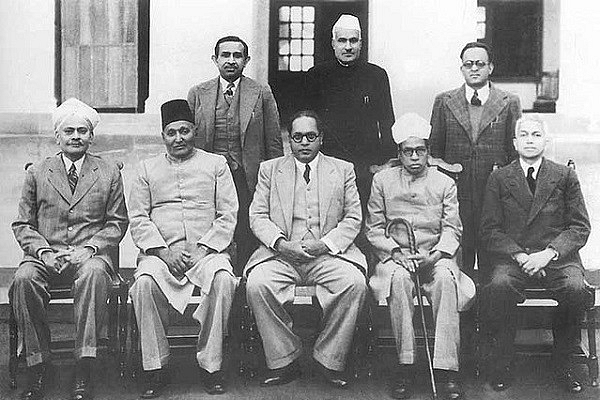

Indian Constitution Drafting Committee chairman Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar with other members on 29 August 1947.

The recent announcement by All Indian Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) that it would set up Sharia courts in every district of India has set off alarm bells for all those who seek to defend the country's Constitution.

The claim has led to a disagreement within the Muslim community. AIMPLB president Zafaryab Jilani has argued that the announcement is not new since such courts have been present in India since 1993. Jilani clarified that they would not operate as parallel courts.

On the other hand, Shia Waqf Board chairman Wasim Rizvi has said that this move is against the Constitution and it could lead to a Kashmir-like situation in the rest of India. Minister of State for Law and Justice, P P Chaudhury, had said all courts in India had to be established by the rule of law, and verdicts delivered by any other court would be going against the Constitution.

This development revives the need for a uniform civil code (UCC), as it would halt extrajudicial institutions of the Sharia court kind from cropping up in the country.

The Indian Constitution prescribes a UCC for all Indians through Article 44, which is one of the directive principles. It states: "the State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India". Unlike fundamental rights, directive principles can't be enforced by the judiciary. But they impose a moral obligation on the state to fulfill the recommendations provided under this section. In spite of this obligation, Article 44 has been played down by the so-called secularists, who seek to postpone or permanently bury the implementation of a UCC. They argue that a UCC imposed by a majority on the minorities would lead to communal disharmony and threaten freedom of religion in India.

A response to arguments against a UCC can be found in a speech given by Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, a member of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly. When asked how any objection could be raised against a UCC in a country, he said, the move would neither put any religion under danger nor disturb amity in the nation. "The article actually aims at amity. It does not destroy amity," he had said.

Ayyar had assured that no one religion would be influencing the nature of a UCC that would apply to the entire country. He also said that there is no use in clinging to the past while going about the task of building a united India.

He posed an important question to the Constituent Assembly: "are we helping those factors which help the welding together into a single nation, or is this country to be kept up always as a series of competing communities?"

This same question needs to be posed today to those claiming to be loyal to the Constitution and secularism, yet are staunchly opposed to the UCC.

Further, Ayyar had pointed out how people had accepted a common criminal code from the British, and said, a UCC would only be an extension of the process started by the British in criminal law. Ayyar cited the example of European nations, which had a UCC and assured the House that the measure would not be forced upon any community. He asked his Muslim friends in the assembly to have faith in an indigenous government and democracy.

The leaders of minorities and protectors of the Constitution must heed to the wise words of Ayyar. A UCC would also promote the idea of oneness among all Indians.

Personal laws that are outdated and promote the feeling of 'otherness' in society can also be against the fundamental rights of citizens. One such case was brought to the attention of the Supreme Court in 2005. In this case, a Sharia court had asked a woman to leave her husband and children, and live with her father-in-law, who had raped her. The court had ruled in 2014 that Sharia courts have no "legal sanction" and accepting their diktats was "not obligatory". If the matter was not brought to the attention of the Supreme Court, the rights of the woman in question would have been violated. One can only imagine the number of atrocities that have gone unnoticed in the eyes of the public or the judiciary. Therefore, institutions like Sharia courts must not only be condemned but also outlawed by Parliament.

The case for UCC has never been stronger than it is today. In a rapidly modernising world, where human rights are sacrosanct, all aspects of medieval and unequal laws must be discarded.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest